Door County’s Kind of Skyscrapers

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

The tallest natural point in Door County is not the scenic Sven’s Bluff or the ascent from Ellison Bay. It is an 860-foot mound in the town of Brussels on the county line between Door and Kewaunee. The mound is just a smaller brother to an 870-foot mound in Kewaunee. On a clear day, climbing the hill might result in a view of Green Bay to the west.

But this fact is far from Door County’s scenic truth. The high bluffs and rolling waterfront roads are some of the most iconic and important in Wisconsin. At three points from Southern Door to Washington Island, wooden towers stretch above the tree line, redefining the idea of a scenic view.

These towers – in Potawatomi State Park, Peninsula State Park and Washington Island – support thousands of visitors each year and are a landmark for the county. Climbing each is often seen as a rite of passage, solidified by carving a name and date in the weathered wood.

Their value to the county’s tourism industry is well known, but in the past 100 years, their importance to local residents and industries is a quiet fact weaved through the fabric of everyone from Potawatomi to Washington Island.

While they are known today as places for scenic observation, the towers originally served the purpose of detecting wildfires.

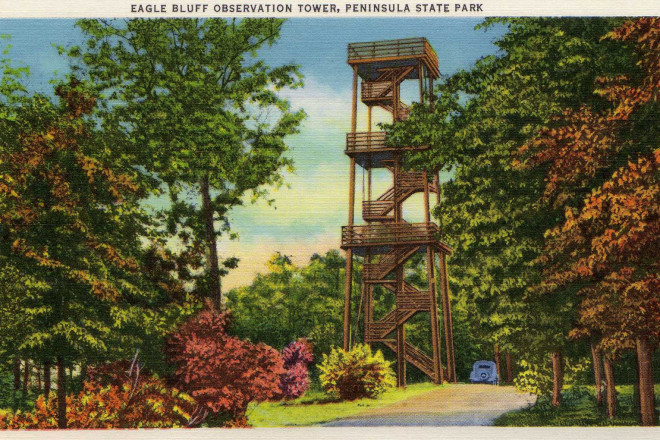

“Two lookout towers to aid in detecting forest fires have been erected on Sven’s Bluff and Eagle Bluff, which are connected by telephone with the superintendent’s residence and the local exchange,” wrote the Wisconsin State Conservation Committee in their 1915-16 Biennial Report. Both towers were built in 1914.

When the towers in Peninsula State Park and Potawatomi State Park were erected, citizens surely had stories of October 1871 burning in their minds.

The Great Fire of 1871 is the deadliest firestorm in United States history. The fire started in Peshtigo, just west of Marinette, and burned down to Green Bay before crawling back up the Door Peninsula.

“The people of Sturgeon Bay had watched with great terror this approaching storm of fire and knew that down there in the smoke wrapped forest country of Brussels and Gardner a terrible calamity had taken place,” Hjalmar Rued Holand wrote in History of Door County, Wisconsin, The County Beautiful. “This tornado of fire swept up from Brown County, overrunning the towns of Union, Brussels, Forestville, Gardner, Clay Banks and Sturgeon Bay.”

The day after the fire broke out in Peshtigo, the Great Chicago Fire burned more than three miles of the city. The impact of the Chicago fire overshadowed the rural devastation in northeast Wisconsin, but the lookout towers were built in hopes that they would never have to sweep up the ashes of their lives again.

“Both towers [Eagle and Sven’s] were valuable as lookouts for forest fires, since the park was full of dry, dead grass and brush,” wrote William Tishler in Door County’s Emerald Treasure: A History of Peninsula State Park.

The ledger from A.E. Doolittle, the first manager of Peninsula State Park, lists payments to men for fire watch duty. Although their jobs required focused diligence, the view wasn’t too bad either.

Both towers at Potawatomi and Peninsula State Park offered views across the bay, giving visibility to the area where the Great Fire of 1871 started years before.

On June 22, 1915, the first fire detection flight in the world went over Wisconsin’s northwoods in Vilas County. Jack Vilas volunteered to use his plane in helping the Department of Forestry find wildfires before they got too large. With the beginning of advanced forest fire technology, reliance on the naked eye for fire detection dwindled.

The cost of this fire safety method is steep and, over time, states stopped seeing the benefit of having eyes up high.

“It costs a lot to have someone sit and watch all day,” said Henry Isenberg, who spent 25 years at a fire tower in Massachusetts. “They have to pay salary, insurance, upkeep of the tower, and most states don’t want to do that.”

Towers across the country are being decommissioned, including many in Wisconsin. Today, there are 72 active forest fire lookout towers in the state, down from 95 towers in 2000.

Door County is not high risk for forest fires relative to the rest of Wisconsin and although the county’s towers were originally constructed with fire detection in mind, they were also open to the public for viewing pleasure.

Following several safe years since the Great Fire of 1871, the towers were only known for a beautiful view. Tourists climbed the steps more than forestry officials and the towers became an attraction to the county.

An issue of the Door County Democrat, released on Christmas Day in 1914, claims, “from the one erected on Sven’s Bluff, a view can be seen across the peninsula to the eastward, out onto Lake Michigan, and to the west the waters of Green Bay.”

Whether the view from Sven’s Tower actually stretched across the width of the peninsula is impossible to know. The tower was torn down in 1947 and never replaced.

But before Sven’s tower was taken down, Eagle Tower faced demolition.

After being lauded as a tourist attraction and climbed by thousands of visitors every year, the tower fell into disrepair. It was dismantled and completely rebuilt in 1932 with Douglas Fir logs imported from Washington state.

Unlike the original construction of Eagle Tower, which used little more than axes, saws and strong arms to erect, a public works crew used horses, tractors and trucks to haul materials to the building site.

The crew wrapped cables around surrounding trees and used them as a pulley system to raise the four main support poles. Even today, there is a tree stump still wrapped with rusted steel cables just north of the tower that was used to raise the structure.

Although Roosevelt’s New Deal-era public works program, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), did not have a role in constructing the tower, they did build the stone wall lining the bluff along the feet of Eagle Tower.

The CCC was limited to unskilled men between the ages of 17 and 28. In Peninsula State Park, the men camped near Gibraltar High School while working on the park’s infrastructure.

With these spare hands sitting at their doorstep, park officials entertained the idea of replacing Sven’s Tower, but they decided that Sven’s Bluff already had a scenic view at nearly 200 feet above Green Bay.

Around the same time Eagle Tower was being rebuilt, the Village of Sawyer looked to build a tower of their own to watch over Sturgeon Bay.

The Sawyer Commercial Club promoted economic development in the Village of Sawyer, which was the original name for Sturgeon Bay’s west side before it was annexed in the late 1800s. The club financed and volunteered to erect the tower in Potawatomi State Park.

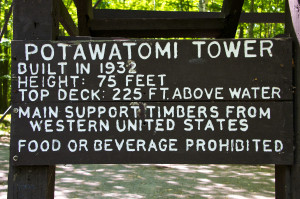

Builders planned for the tower to be the exact height of Eagle Tower in Peninsula State Park, but the final measure came up one foot short – topping out at 75 feet.

It took the group seven weeks to construct the tower and their efforts were rewarded as attendance quickly approached the numbers visiting Peninsula State Park.

In the first week of the tower opening, the Door County Advocate reports, “25 cars parked around the structure continually,” in its issue on October 9, 1931. The new structure offered views never before seen in Door County.

“Monday, the air was so clear that it was possible to see over a radius of about 25 miles. Menominee and Marinette buildings stood out distinctly. To the north and northwest Green Island, Chambers Island, Hat Island and the Strawberries were plainly visible, while to the east one could see the waters of the canal and Lake Michigan.”

The tower on Washington Island was not built for tourism as much as the locals on the island. The idea to build a tower was a simple one.

“It just came up at a meeting and the town voted on it,” Gail Larson Toerpe wrote in the Washington Island Observer on July 17, 1997. From then on, the construction was a community affair.

At the town board meeting in May 1968, the town contracted Richard and Emil Jensen to build the tower and construction began in July. In the planning stages, residents that lived near the tower’s proposed location granted permission for builders to haul materials through their land.

Even with permission, there was not enough room for a crane, electricity lines or any equipment except the builder’s shoulders to carry the wood up the steep hillside of Reykjavik Peak.

After the Jensen brothers finished the tower, peak seekers still had to climb the rough terrain up to the base of the tower. An early 1900s photo from the collection of Arbutus Greenfeldt, former chair of Washington Island Town Board, shows women in white skirts struggling up the mountain for the view before the tower was built.

The tough climb was made easier in 1989, 20 years after the tower was built, when a staircase to the base of the tower was constructed. The Bethel Church on Washington Island spearheaded the staircase project when one of its members looked for a memorial in his wife’s honor.

“Instead of having to crawl up by means of slippery rocks, these lovely steps have been built and given to the Town of Washington by George Platzman in memory of his late wife Harriett, who loved to climb the mountain but found the climb very difficult,” read the Bethel Tidings newsletter on July 23, 1989.

With the finish of the steps at Mountain Park Lookout Tower, the three beacons across Door County were established. They have served tourists and locals in gaining a new perspective on the peninsula and their wood is steeped in history of the people and industries that have created Door County’s success.

The Towers Today

After decades of dormancy, the county’s first two towers began showing signs of weathering. By this time, the importance of the towers in attracting visitors and as a landmark for the county was well established and park officials knew that the fate of Sven’s Tower could not be repeated.

Potawatomi Tower was closed in 2012 after a major crack in one of the main support beams was discovered. The repair, which was the first major repair since the construction of the tower in 1932, took nearly two years while park officials had to find a living white oak tree big enough to provide a 22-foot long beam.

While each tower holds equally incredible views, Eagle Tower in Peninsula State Park stands tallest as the icon of the county’s landmarks.

The park performed minor safety improvements and repairs beginning in 1972, including new hardware and decking.

But visitors climb Eagle Tower twice as much as the other two wooden waypoints. This fact explains why Eagle Tower fell into such severe disrepair.

On May 20, 2015, park officials contracted with Edge Consulting Engineers to inspect the structural soundness of the tower. The report recommended tearing down the tower and rebuilding a new one.

Cracks throughout the wood, loose tie rod X-bracing between columns and supports that are split down the middle and rotted constituted the recommendation that the tower is beyond saving.

Recognizing the importance of the tower to the area’s tourism industry as well as its cultural significance in the county, state park officials and the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) may fast-track the project.

Typically, capital development projects, or infrastructure improvements, require cost estimates and approval before the project goes into the seven-year capital development plan.

Kimberly Currie, deputy director of the Wisconsin Bureau of Parks and Recreation, said they do have some flexibility within that seven-year plan.

Although the project was too late to make it into the 2015-17 state budget, Currie said the DNR can look at what other planned projects they are able to defer in order to secure the funds to tear down and rebuild the tower.

The stairs leading to the Washington Island Tower are a challenge of their own. Photo by Len Villano.

The fate of Eagle Tower sits at the top of a storied history of Door County’s towers. County residents, transient and permanent, constructed each tower for a different purpose and each stands at a different place in Door County’s long shoreline and even longer history.

By the Numbers

Door County’s Towers

186

Steps to the top of the Mountain Park Lookout Tower

33

Years the tower at Sven’s Bluff stood before it was torn down

$1,061.92

Cost to build Eagle Tower in 1914

$25,126.81

Cost to build Eagle Tower in 2015 dollars

225

Feet above Green Bay at the top of Eagle and Potawatomi Towers

7

Weeks it took to build Potawatomi Tower in 1931

109

Steps to the top of Eagle Tower

250

Number of tents at Camp Peninsular for CCC workers

Who Is Luke Archer?

Not everyone who climbs the towers inscribes their name in the wood for their place in Door County history, but it must be pretty close. One man has made his mark on Eagle Tower enough for everyone.

I first noticed Luke Archer’s name written on the second platform of the three-story tower. It was during a festival in 2007 and my family and I were taking a gamble of seeing fireworks from the tower while I carved “Jack ’07” on the handrail with a pocketknife.

Next to my carving, Luke Archer had written his name in fat, black permanent marker. There was no date and no clue as to who he was.

As more years went by and I visited the tower on my annual family vacation to the state park, I noticed his name popping up in more places along the 109 steps to the top. It was always written in fat, black permanent marker with a complete disregard for whatever was already inscribed in the location Luke Archer wanted to write.

At the time, a quick Google search yielded nothing. Perhaps the poor handwriting and lack of any dates was a deliberate attempt at anonymity.

But while writing this story on the county’s towers for Door County Living, I gave the search one more try.

On Foursquare.com, a site for visitors to post reviews of the places they have been, a man named Bill Neuman wrote a note on August 10, 2010.

Watch out for Luke Archer.

– Jackson Parr