Hitting A Legend: Roy “Decker” Woldt

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

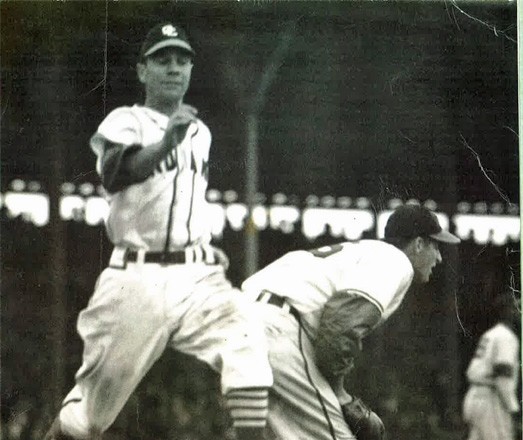

In the photo Roy Woldt is floating past first base, legging out what might be a routine base hit, his feet airborne as he sprints past the bag, his pants billowing loose above his stirrups. Behind him first baseman Mickey Vernon steps aside.

But farther in the background a pitcher stands on the mound, looking toward the outfield, unconcerned with the man who has just reached first base. He’s the man who makes the hit anything but routine. That fuzzy figure, long-legged and lanky-limbed, is LeRoy “Satchel” Paige, one of baseball’s most enduring legends.

Roy Woldt (left) legs out a single as Mickey Vernon steps aside in an exhibition game in 1947. Satchel Paige (background right) waits on the mound.

Over a 15-year career played in several different leagues, Woldt would face Paige three times, the first in 1939 while playing in Eau Claire. Woldt said he had no chance.

“I promise you there was no way you could get a hit off Satchel Paige back then,” he said of the man who was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971.

The next time Woldt was 21 and in the military, getting in some pro ball on the side with a team in Belleville, Ill. He fared no better, going hitless against Paige for a second time.

Paige was already past his prime then, having spent the best years of his career building his legend in the Negro Leagues and in barnstorming exhibition tours. Like fellow black greats Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell, Paige was denied a shot at Major League Baseball by baseball’s color line until Jackie Robinson broke through in 1947. When Paige finally got his chance in the Majors in 1948 he was thought to be around 42 years old – the oldest rookie in baseball history. Even at his advanced age he was a star, helping Cleveland win the pennant with a 6 – 1 record and 2.47 earned run average while drawing some of the largest crowds in big league history.

In 1947 Woldt got his last crack at Paige when he was playing for the Cleveland Indians AA affiliate, the Oklahoma City Indians. They played the Kansas City Monarchs in an exhibition game when Woldt came up to bat again. This time he finally solved the riddle that was Satchel Paige, getting a single, and a claim to fame to go with a career that began on the ballfields of Door County.

County League Years

Roy “Decker” Woldt was born in Egg Harbor, spending his early years in a small home on County T about two miles from Murphy Moore’s tavern in the center of town, but when his parents divorced he was sent to live with family in Baileys Harbor.

It was there, playing on the old ballfield that was located in the center of town next to what is now the Cornerstone restaurant, that Woldt earned the nickname that stuck with him for life.

“My dad or uncle bought me a catcher’s mitt, and I tied that thing around my belt,” he remembers. “So I was always the guy with the catcher’s mitt, which we called a decker, and people just started calling me Decker. Then they shortened it to Deck. Everyone had to have a nickname back then.”

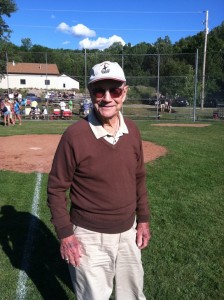

Roy Woldt on the Egg Harbor baseball diamond after the 2011 Door County League Championship game. Woldt was inducted into the Door County League Hall of Fame in 1993. Photo by Myles Dannhausen Jr.

To this day, if you ask an old-timer if he played with Roy Woldt, he’ll pause and ask, “You mean ‘Deck’ Woldt?”

Though he lived in Gibraltar School District, Woldt attended Sturgeon Bay High School because they had a much stronger athletic department at the time.

“The best athletes in Baileys Harbor all went to Sturgeon Bay,” Woldt said. He played football and basketball for Sturgeon Bay, but when summer baseball came around he kept his diamond talents at home.

Even as a teenager he built a reputation as one of the best ballplayers in county history. He learned the game from Gordy Brann, then the groundskeeper at Maxwelton Braes, and Woody DeJardin, another great player of the era. Together they would lead Baileys Harbor to the league title in 1938, earning a trip to the state amateur tournament at Borchert Field in Milwaukee.

A win there would send them to the national tournament in Wichita, Kan., a trip Woldt wanted desperately. But it wasn’t meant to be, not yet anyway. The trip did put Woldt on display for pro scouts, however.

Both he and DeJardin were signed to minor league baseball contracts, DeJardin with Detroit and Woldt with the Chicago Cubs Class D affiliate in Eau Claire.

“We were probably the first guys from Door County to have a real chance at pro baseball,” he recalled.

In Eau Claire Woldt made it to the final day of spring training, then the manager called him into his office. They could only carry 16 players, he said.

“Kid, I’m sorry, but I’m gonna let you go,” Woldt remembered. “But there’s a factory in town that will take you, and you can play in a league here.”

Woldt went to work at that factory, the Gillett Rubber Co., and played ball in Eau Claire until he enlisted in the service in 1940. Like so many of his generation, World War II would interrupt his life. He served until 1945, playing ball whenever he could.

Woldt loved the game, and when he got out of the service, he continued pursuing his dream, even as he approached old age for a minor league ballplayer. Back in the states he would find his way to the West Texas/ New Mexico League, continuing his pro pursuit. After an impressive performance in the Army All-star game the Cleveland Indians signed him to a contract with their AA affiliate in Oklahoma City.

After bouncing around in various positions for a couple years, he entered the 1949 season as the starting second baseman for Oklahoma City on opening day. This, he felt, was his last shot to show his stuff.

A load of friends and family came down from Wisconsin and elsewhere to see him play, but then when he suited up on game day he found that his name was not in the lineup. He went straight to his manager to find out what was going on.

“Deck,” his manager told him, “I meant to tell you, but they need an outfielder back at Class A in Pennsylvania.”

It was devastating news. Woldt had played a lot of outfield in addition to second base, and the Indians wanted to send him down a level to Class A Wilkes-Barre in Pennsylvania. Woldt had already had a stint at Wilkes-Barre and wasn’t enthused about heading back for another one, or taking a step down so late in his career.

The old Baileys Harbor baseball field where Roy Woldt played in the 1930s. The field was located next to where the Cornerstone Pub now stands.

He realized that he wasn’t facing a simple choice, but he knew he had to make it now, at the ballpark, just moments before what he thought was going to be his greatest opportunity.

Would he travel across the country and continue his Major League dream, or give up the dream and get on with a life without pro baseball?

“I refused to go,” he said, a decision he sometimes questions to this day. Wilkes-Barre was much closer to Cleveland, and in those days proximity sometimes made a difference. “Maybe I made a mistake in not going back. I know you had a better chance of making the big club if you were nearby.”

But that decision opened other doors. “It’s probably the only reason I finished college,” he said. He had a connection at a local college, where he was able to get his degree on a partial scholarship while playing semi-pro baseball. He became a teacher and coach in Pampa, Texas, teaching history, science, and physical education for 31 years.

And he got another crack at Wichita. He hooked up with the Elk City Elks, an Oklahoma semi-pro team in the nearby Red River League. They had a prodigious slugger named Joe Bauman, who once hit 70 homers in a season and would lead the team to the Oklahoma state championship. A decade after falling short with Baileys Harbor, Woldt was heading to the national tournament with Elk City. They didn’t win it all, but Woldt had come full circle.

He never got that cup of coffee in the Majors, but at 91 he can call himself one of the greatest baseball players Door County ever produced, and certainly the only one who ever notched a hit off the man the Sporting News once named the 19th best baseball player in history, Satchel Paige.