Warmer, Wilder, Wetter

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Climatic changes may sound small, but impacts are major in northeastern Wisconsin

The Midwest’s air-conditioned playground won’t be spared from the adverse effects of worldwide climate change, but everyone can work together to slightly lessen the impact, Wisconsin scientists say.

During a recent program at Crossroads at Big Creek in Sturgeon Bay, Bart DeStasio, the Singleton Professor of Biological Sciences at Lawrence University, summarized findings by the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI). His “Warmer, Wetter and Wilder” presentation provided a picture of what lies ahead for Door County as average annual temperatures continue to increase, winter and spring get rainier, and extreme storms and periods of drought pop up more frequently during the summer.

Fragile Fens and Forests

Door County could see more gradual temperature increases than other parts of Wisconsin, but DeStasio can’t conclude that the peninsula would see fewer negative impacts than other parts of the state. Scientists consider most of the county to be ecologically fragile. Take, for example, sensitive plant habitats that are unique to Door County because of its relatively cool summers and mild fall and early winter.

“Being a peninsula is a moderating factor, which is why you have such unique plant communities found in Door County,” DeStasio said. “The boreal forests you have in Door County are there because of that moderating influence on the seasons. But our boreal forests are at the very extreme southern end of what is climatically typical for a boreal forest. You have to go farther north in the mainland and into Canada before you reach many of those boreal forests.

“There are unique micro habitats in Door County, and because of that, the effects of climate change are going to be different than they are in the main part of Wisconsin, where you don’t have the warmer waters moderating temperatures in the fall,” DeStasio said.

If more trees die off because of temperature increases, drought or standing water after midwinter thaw or rains, some plant life in the understory would also die off.

“That boreal community is in some ways self-reinforcing,” DeStasio said. “Plants that survive in a boreal-forest community are there because they all work together in a lot of ways. As that community breaks down, it becomes more fragile.”

One of the recommendations of the WICCI group is the need to protect those forests and conserve other sensitive habitats – wetlands, natural shoreline and native northern pine woodland, to name a few – because they’re already under stress. Door County champions – including Door County Land Trust, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, The Nature Conservancy, the county parks, The Ridges Sanctuary and Crossroads at Big Creek – have already spent decades acquiring, protecting, restoring or even creating ecologically important parcels.

Those entities can’t prevent temperatures from rising or the increasing frequency of dry spells and severe storms, but they are working to prevent additional stress coming from humans, neighboring properties and nonnative species.

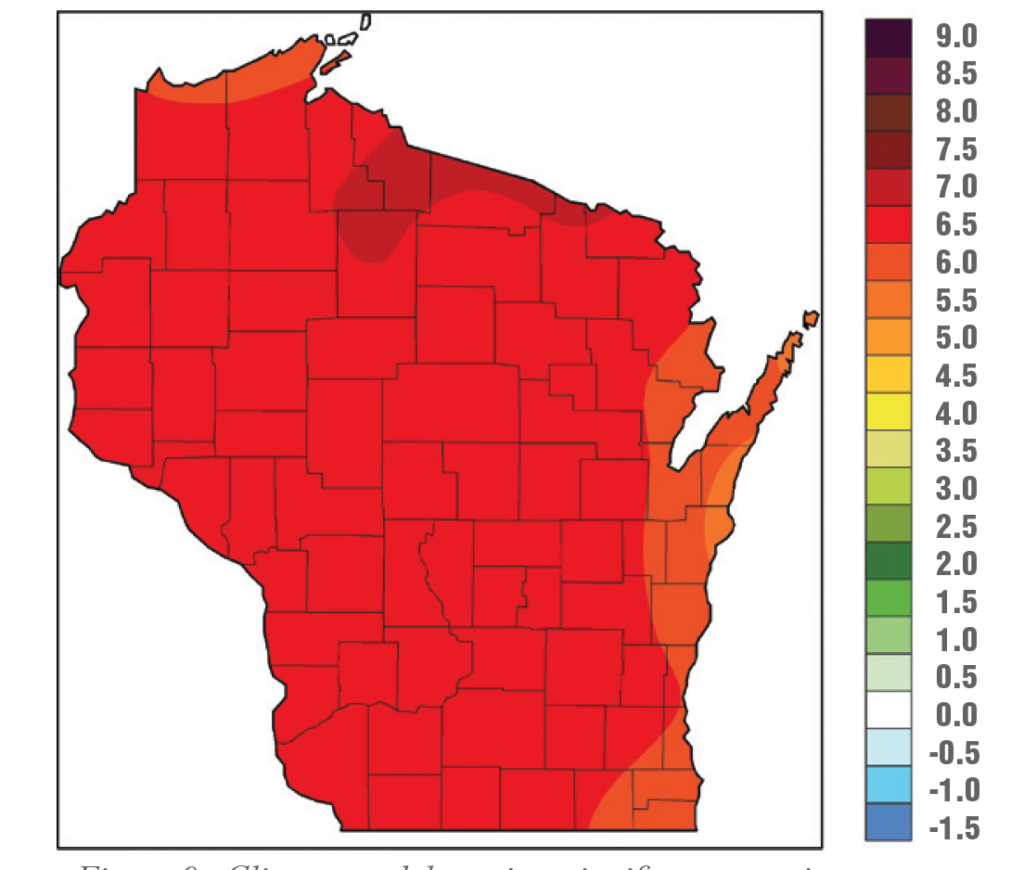

The projected change in the annual average temperature in degrees Farenheit from 1980 to 2055. Source: Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts.

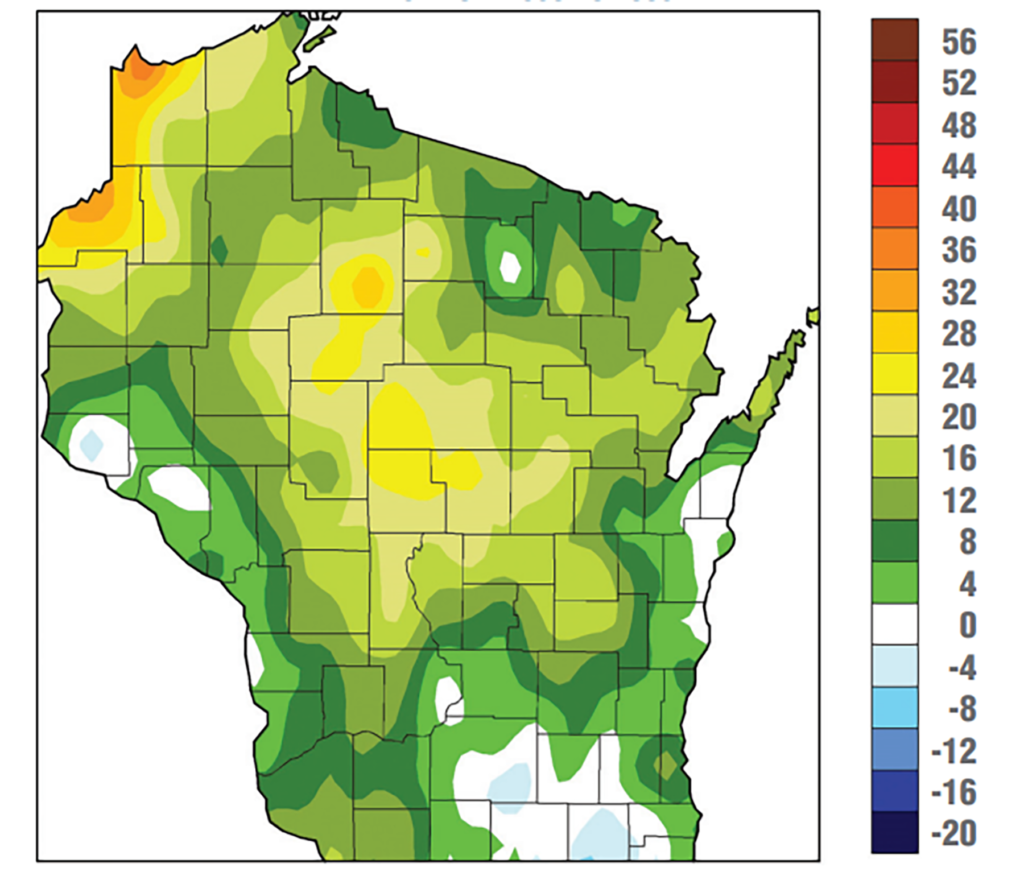

The change that occurred in the length of the growing season in days between 1950 and 2006. Source: Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts.

Temperature Trends

Most of Wisconsin already has seen a two- to three-degree increase in average daily temperatures since 1920, according to the WICCI report. The report further projects that northeastern Wisconsin and Door County will see average overall temperature increases of between 4% and 6% between now and 2050, depending on whether world leaders do something about CO2 and methane emissions or not.

“Most of that warming is going to occur in the wintertime and in spring,” DeStasio said. “That sets up pretty big changes. More often what you’re going to be seeing is precipitation in the winter that’s going to be wet, as opposed to snow.”

Although temperatures should remain somewhat mild in northern Door County compared to the rest of the region, climatic change already is harming the Lake Michigan shoreline and the waters of Green Bay.

WICCI data project that extreme rain events will continue to increase in frequency, resulting in more nutrients and pollutants entering the lake and watershed through increased runoff. DeStasio said communities and landowners can and should work to reduce runoff and the adverse impacts it has on Door County waters.

Precious Days at the Beach

Beach closings on the Green Bay side will continue to increase if runoff is not controlled and temperatures continue to rise.

“One of the big concerns is the bay is going to be warming up,” DeStasio said, noting that relatively shallow spots – such as Eagle Harbor in Ephraim – warm faster than others. “That will encourage algae growth – species such as green algae and sometimes the cyanobacteria [blue-green algae] that’s toxic. Beaches down by Green Bay have been closed for years because of that.

“If you have more intense rains that are running across the land into the shallower water that is sitting there warming up, you’re ending up with more of the bloom, and that will start to eat into the time that you can actually swim in those bays.”

Although toxic or simply unpleasant varieties of algae would be quite visible to beachgoers, other adverse effects lie below the water’s surface. Increasing weed growth and decreasing oxygen levels for aquatic life and fish are a major concern for scientists such as DeStasio.

Warmer waters have contributed to the increasing size of an annually occurring Green Bay “dead zone” that can stretch from north of the Dyckesville area all the way to the mouth of the Fox River. The Green Bay dead zone – similar to the 6,000-square-mile dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico near the Mississippi River mouth – results in part from “high nutrient input” from factors such as runoff, discharges and, DeStasio said, large cattle-feeding operations and poor farmland practices.

The “dead-zone days” south of Dyckesville in Green Bay increased markedly starting around 2006, when there were 10 summer days when waters near the lake bottom within the zone could not sustain life. Scientists recorded 30 dead-zone days in 2015 and more than 20 in 2018. Cold-water and deep-water organisms die off in that zone, and fish such as burbot (lawyers) and cisco must move to other parts of the lake. The bay is also seeing warm-water species thriving.

The dead zone results from eutrophication (high nutrient input), and extreme rain events deliver nutrients straight into the lake. Historically significant downpours have increased during the past 50 years, and that trend is not slowing.

“There have been 21 100-year-rain events in Wisconsin in the past 10 years,” DeStasio said. “They’re happening much more frequently. Wilder, more frequent, intense events are what we have to think about. How do we adapt to that sort of climate, because it’s a different pattern from what we’ve seen for the past 100 years?”

This is the first of a two-part story. Part two will discuss solutions to lessen the blow of climate change.