A Review – “Away”

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

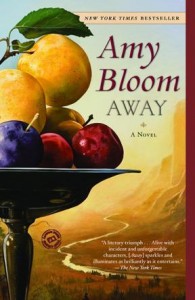

Away

By Amy Bloom

Random House, 2007

Away is a dark story. The central character, Lillian Leyb, is 22 when the book opens in 1924 with a pogrom in Russia that leaves her bereft – her husband and parents killed before her eyes, and her three-year-old daughter disappeared. By the time Lillian reaches New York, her story is already more than anyone can bear to hear. Although it is not quite as horrific as Morrison’s Beloved, one might still say, as the narrator does at the end of that novel, "This is not a story to pass on."

Here is an abbreviated catalogue of the reasons why: One of the gentile soldiers who butchered Lillian’s family cuts her from shoulder to hip before his commanding officer talks him out of the house. Her aunt misreports having seen her daughter floating in the river. Once Lillian arrives in N.Y., she becomes the mistress of a gay Jewish actor and his father. Neither will give her the money for her overland journey so she stows away in a broom closet. She arrives safely by train in Seattle’s King Street Station but leaves by the wrong door and is quickly beaten and robbed. Rescued by a "Colored" prostitute, she becomes an unintentional accomplice in the death of a pimp. In Alaska, she is found in a heap by a lawman that cleans her up but finds it necessary to store her for the winter in a women’s prison to ensure that she does not choose certain death on the trail north. As is true of most picaresque novels (think of Fielding’s Tom Jones, for example), the protagonist must become a rogue in a rogue’s world, yet because she is the underdog, our sympathies remain with her, sometimes to the point of laughter. But in two years, this young woman sees more destruction than my extended families encountered in the last hundred years, and there is nothing funny about that.

Why did Bloom tell this story? And why now? Is Lillian’s journey so hard because she is a Jew? After the Pogrom in Russia, no race or creed seems to have a monopoly on virtue or vice in this book. Is it because the new world Lillian enters has not yet mastered law and order? I doubt it. The men who use her in New York are "civilized" enough. The Yiddish phrase "Az me muz, ken men" (when one must, one can), along with "Ez iz shver tsu makhen a leben" (it is hard to make a living) are verses in a praise song for "Opportunity" that all the characters know, regardless of their education or position. Fear of poverty and its partner, the hatred of small differences, is another possible explanation for the kind of depravity that fills these pages. The world in 1924 – 1926 (and now) is a dangerous place in Bloom’s account, not because of "Reds" and "terrorists," but because of what I have always been reluctant to call "human nature." Human beings in Bloom’s vision are not as bad as, say, Edward Jones would have us think in his The Unknown World, but they are often self-centered and greedy.

The kinds of things that happen in these pages, however, are more likely to happen when people are away from a functional world where food, warmth, sleep and respect for an individual’s boundaries and aspirations are assured. It makes sense to read Bloom’s story as a metaphor for what we both fear and often find will happen when we move away from the people, language, and customs that constitute "home." In these circumstances, it is often hard for anyone not to become a rogue among rogues.

Even in the worlds away from home, however, there can be choice, love, and decency. Although her decision to leave Russia is framed by gentile hatred and her aunt’s greed for the family home, Lillian’s choice to seek her missing daughter is motivated by love for the only being she considers her responsibility. When her friend Yaakov asks why she is so determined to undertake a hopeless search for Sophie, she replies, "Because she is a little, little girl. Not that she is mine. That I am hers.” Evidence of human decency turns up in the most unexpected forms on Lillian’s journey: a gift of Roget’s Thesaurus that gives her pleasure in learning English; maps of the Northwest sewn inside her overcoat; a cigarette on the trail; a pair of warm boots.

Without such gestures, neither she nor we could hope to survive. This is who we are – needy and often greedy, but still able to reach out to others along the way. One act of decency enables another. What finally allows Lillian to stop her headlong journey to the end of the earth is the equally outrageous determination of another human being to join her. But I will not spoil the ending.

I strongly recommend this book-especially to anyone who harbors a secret belief that everyone else is crazy (or wrong, dangerous, greedy) except thee, me and the lamp post, and sometimes I worry about thee. We are a nation whose families often experienced unspeakable trials in the spaces away from their homes in the centuries beyond our memories. In a global economy, many are once again finding it necessary to go away to find work. The book acts like the two lead disks one of the women prisoners gives to Lillian to build up her muscles for the Telegraph Trail; she says, "No run-down lazy bitch is walking to Siberia.”