A Third Coast to Dive: Remembering On The Rocks dive lodge

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Fifty years ago, during the first few hours of the new year, the phone in a wooden A-frame at the tip of the Door peninsula would ring madly. At the other end of the phone line, eager diving enthusiasts would secure their bunk bed for a weekend during the coming summer.

Jim Robinson recalls those summer weekends: packed into a car after work on Friday, coming up from Chicago with $10 and his diving gear, caravanning along state highways and county roads to arrive at On The Rocks dive lodge just before midnight.

On The Rocks was a passion project for Gene Shastal, a Chicago resident who purchased the waterfront A-frame off Wisconsin Bay Road near Gills Rock to host ardent divers each summer. In doing so, he created a nationally recognized diving community.

“We have a third coast to dive,” Robinson remembers reading in a diving magazine, referring to Door County in the ranks with the West and East Coasts. “The purpose of On The Rocks was to put Door County on the map as far as diving. Gene was a diver and wanted to promote diving.”

Door County already had a small group of local divers who relished floating above the giant shipwrecks that the area is so well known for. They included the owner of Thumb Fun, Doug Butchart; and Herbert Gibson of Gibson’s Resort on Washington Island.

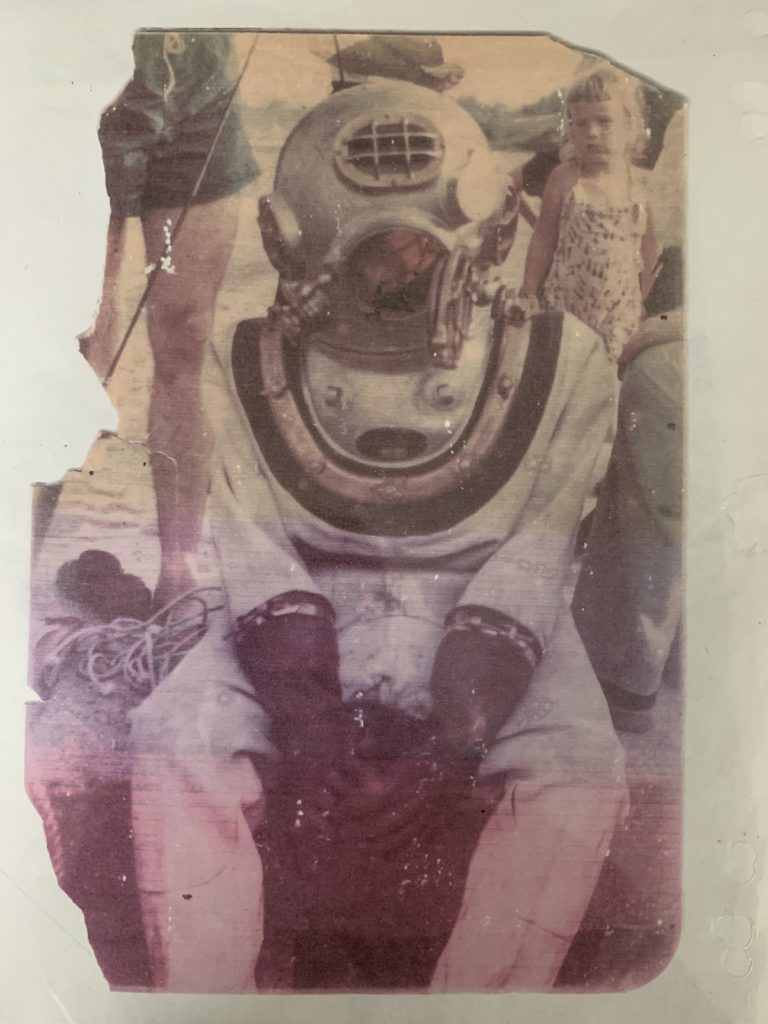

The dive scene was both born out of, and contributed to, the wealth of shipwreck history in the surrounding waters. A 1969 feature on Door County in National Geographic showed a full-page image of Shastal and his On The Rocks manager, Bob Lapp, working on a 500-pound windlass from the 1888 shipwreck of the schooner Fleetwing. The towering, chalet-like On The Rocks lodge sits in the background.

“We want to encourage the preservation of wrecks and stop them from sometimes being used as firewood — literally burned up,” Shastal told William Ellis, the author of the National Geographic piece.

“People knew there were some shipwrecks up there, and divers at On The Rocks started discovering more,” Robinson said. “Back then, they were finding new wrecks every year, and word was getting out.”

Robinson’s description of the lodge and the like-minded people who viewed it as another home calls to mind the climbers on the great walls and valleys of the West, who affectionately call themselves “dirtbags.”

A room full of divers would swap stories from their $10-a-night bunks as the sounds of waves crashed on the shallow bluff outside and the smell of a fire’s ashes floated in from the hearth in the main hall.

There was a room for women and a room for guys, with a few private rooms for the big spenders. A boat full of divers would leave in the morning, stopping anywhere from the known wrecks on the near shore to stranger waters north of Washington Island.

After docking for the day and a grocery run to Sister Bay, the group of friends and strangers grilled steaks on the dock as the sun set over the waters they had spent the day exploring. Sometimes they would dive at night with underwater lights and a fire on the shore as a beacon to find their way back.

“It was a really neat experience, all on the cheap,” Robinson said. “People say On The Rocks was the birthplace of Great Lakes recreational diving. That’s where it really started.”

Shastal’s son, Bill, started managing On The Rocks with Lapp during the early 1970s, but they butted heads, causing Lapp to leave On The Rocks and open his own dive shop at the Shoreline in Gills Rock.

Robinson said Bill Shastal was hesitant to take groups on the water and had a challenging relationship with some of the longtime divers. Over time, the phone in the lodge stopped ringing off the hook on New Year’s Day. Then it stopped ringing at all.

In 1994, Robinson bought the Shoreline and operated a dive shop there for the next 13 years. During that time, as other owners closed their dive shops, new ones did not spring up in their place. Today, most divers simply drive up and access the water from the shore.

Some health issues during the past decade caused Robinson to stop taking divers out on the water, but he thinks of the peninsula’s storied diving past with opportunistic zeal rather than bittersweet nostalgia.

“If somebody came up here and opened a dive business, a dive boat and a dive shop, you’re not going to get super rich, but it would be busy,” he said. “As long as you were good with people and knew what you were doing, there’s an opening up here for someone.”

It’s unlikely, however, that any significant rebirth of diving in Door County will take place at the lodge where many got their introduction to the waters off the peninsula. Although the structure remains, On The Rocks is now a vacation rental. There may be fewer scuba tanks and rates higher than $10 per night, but the history of the lodge and its eminent divers remains.

The Sad End of the Alvin Clark

Gene Shastal could not have known that his statement about shipwrecks being burned up was such a premonition. In 1969 – the same year as the National Geographic article in which he made his remark – a group of amateur divers led by Frank Hoffman of Menominee, Michigan, lifted the 110-foot, two-masted schooner Alvin Clark off the lake bed about three miles northwestof Chambers Island.

Hoffman intended to restore the Clark using proceeds from the sale of tickets to visitors who wanted to tour the vessel and see the artifacts found within, but the ticket sales were not enough. Hoffman was soon $300,000 in debt as he attempted to restore the ship.

With no help from state or federal resources, and a failed attempt at selling the Clark, Hoffman set fire to it in 1985 so that he could “live a normal life,” according to an Associated Press story on June 19, 1985.

The remains of the Clark were sold to a group of local investors who intended to restore what was left. They didn’t end up restoring the vessel, though, and after it was declared a public hazard, the Alvin Clark was completely destroyed in 1994.

Local maritime historian Jon Paul Van Harpen said the issues with the Clark contributed to the passage of the Abandoned Shipwrecks Act of 1987, which transfers the title of a shipwreck to the state in which it was found, preventing divers and scavengers from dredging up fragile underwater history.