Before Books, John Maggitti Helped Disarm Nukes

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Sometime in the early 1990s John Maggitti was at a Soviet air base – Sharomy Naval Air Base on the Kamchatka Peninsula – watching several dozen live nuclear weapons from the former Soviet Union get loaded onto a FedEx 747 for a seven-hour flight to Naval Air Station Oakland in California.

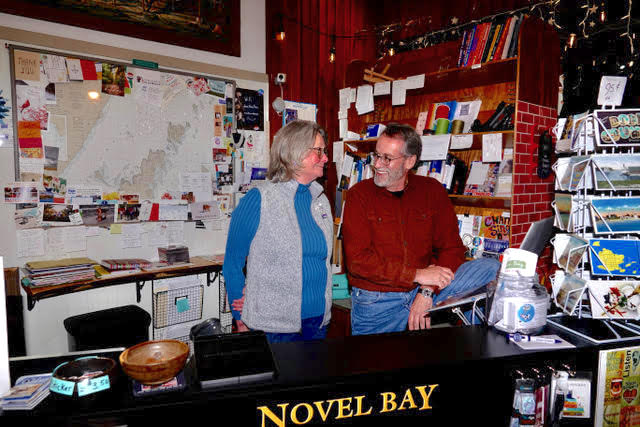

Maggitti was working as a weapons consultant for Barry Research, a contractor at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory operating under the United States Department of Energy. A Ph.D. in high-energy physics from Johns Hopkins University, Maggitti was a long way from his future endeavor as the co-founder of Novel Bay Booksellers in Sturgeon Bay.

The weapons Maggitti was observing that day ranged from artillery shells to 10,000-pound bombs, packed into custom-made fiberglass containers, he said during our conversation, and pulled out his cell phone to show arrays of the containers at the air base.

“City killers – a 1.2-megaton weapon,” he said. “I’m talking lay-waste-to-Philadelphia-size stuff. Set it off at 10,000 feet in the air, and Philadelphia doesn’t exist anymore. It’s all gone. Everybody’s dead. It’s a smoking pit in the ground.”

Maggitti pulled up another photograph on his phone.

“There you go. That’s a six-inch artillery shell with an eight-kiloton yield – about half the yield of the Hiroshima bomb.”

After the weapons had arrived in California, they were trucked to Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s Superblock, where Maggitti and other specialists figured out how to take them apart.

“They bring one weapon out at a time, and we set it on the stainless-steel table, and then we walk around it for a couple days. Nobody touches it because you don’t know what to touch. Your first priority was to get it open, find the battery and get that out.”

Unlike American weapons, which have special fuses to keep them safe, the Soviet weapons didn’t come with an off switch.

“You make a detailed inventory of all the screws in the attachments because you may have to make tools to take it apart,” Maggitti said. “The Soviets weren’t real consistent with what fasteners they used. But somewhere down the line – I can’t tell you how many days it is – you end up with this fully disassembled, active nuclear weapon.”

Each step was documented in great detail because the lab staff would eventually ship the weapons – with the manuals about how to take them apart – to Pantex in Texas, which had the contract to do the actual work on thousands of weapons.

“What we needed was one of everything. If you give us that, we can figure it out,” Maggitti said. “Over a period of time – I’m talking years – we went through this routine quite a bit. We got good at it. We got very good, and we’re not the only ones doing this – some of these are going to Los Alamos, and some of them are going to Sandia down in Albuquerque.”

Once the weapons were taken apart in Texas, the nuclear components were shipped to the reactor at the Savannah River Nuclear Solutions Plant to cook down the uranium and the plutonium and the beryllium, and recover the tritium, which is the most valuable part of the bomb. The process retained the nuclear energy of the weapons, but in a way that made it impossible to use the elements in weapons.

“We basically ground up the parts of their bombs that go boom, and poisoned them in the reactor, and then gave them back in a form that could be used to generate electricity,” Maggitti said. “Gorbachev, and later Yeltsin, were getting back nuclear energy that was worth hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Sometimes the labs had visitors from Washington, D.C., who wanted to see what they were doing.

“Because we’re spending hundreds of thousands of dollars an hour here, OK? I mean, really – we spent a lot of money. This is in the 1990s, and we’re spending hundreds of thousands of dollars an hour.”

They also had visitors from Russia: scientists and military people who were working in cooperation with the Americans on the threat-reduction program. Maggitti also frequently had Russians as guests at his condo near the lab.

“The great thing about having the condo was that at least a couple nights a week, we’re cooking. And I had the barbecue out back, so when the Russians started coming, we started doing ribs and steaks because they weren’t eating this quality of food. Um, and our beer consumption went up significantly.”

One of the Russians went grocery shopping with Maggitti and was impressed.

“I didn’t realize you were so high up in your government as to have access to this sort of store,” he said.

Maggitti assured him that the Albertsons was for anybody. The Russian didn’t believe him.

“Point in any direction, and we’ll go to another one,” Maggitti challenged him. After the third store visit, the Russian was convinced, and he began to cry at all that Russia had sacrificed in the pointless arms race.

The Big Cleanup

The program to remove and decommission nuclear weapons – called the Cooperative Threat Reduction Program and created through the Nunn-Lugar Act in Congress – began in November 1991. It was extended twice, in 1999 and 2006, before Putin canceled it in 2013.

The Bellona Foundation, headquartered in Oslo, called the program’s budget “modest” at approximately $450 million a year – or $8 billion over its two-decade lifespan – “making it one of the cheapest and most effective Defense Department programs in history,” according to the foundation.

The problem the program had to address started with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

“We as a nation, as the leader of the free world and NATO, did not have a plan for what to do when the Cold War was over,” Maggitti said. “And the Cold War just gets declared [as being] over, and we weren’t ready. The Soviets pulled out and left everything behind, including weapons systems, toxic waste. They simply left. All of this was also true of the Warsaw Pact countries – they just withdrew.”

And they left the weapons behind as well, all over the former Soviet Union.

“Their idea of good security was a rusty fence, an old dog and a guy with an AK-47,” Maggitti said. “I’m not making that up. That’s what it looked like when I got there.”

The United States began sending some special-operations troops from the Navy to do an inventory, but they soon said they needed specialized help to identify and evaluate weapons. The Department of Defense turned to the Department of Energy, which manages American nuclear weapons. It, in turn, looked to Livermore Lab but warned Defense, “These are not going to be physically fit guys – they’re going to be the dorks.”

“They grabbed 60 or so of us; they didn’t ask us to volunteer,” Maggitti said. “They sent us to Quantico in Virginia – a Marine base with a training center for some other organizations as well – where we were taught how to drive backward at 70 miles per hour. They taught us how to jump out of the back of C-130s at night over enemy territory. We weren’t in uniform, so we were limited to carrying just a sidearm.”

A range master watched Maggitti practice shooting, then fitted him with a Glock 17 in 1992.

“Welcome to the fun of being in your 30s and as a dork.”

On missions, he traveled with special-operations men.

“These other guys are serious characters. You’re absolutely dependent on them to get you in and out with the goods.”

The Navy needed to give Maggitti and his team some sort of rank, so it made them warrant 2 officers – a rank that hadn’t existed previously.

“And I spent, like, six months trying to figure out who was supposed to salute me and whom I was supposed to salute, so I just saluted anybody,” he said.

Wrapping Up

“They had stuff scattered everywhere,” Maggitti said. “And then they did the stupid things that Communists do, which is they left all their waste in barrels and put it in caves. So we had to go find that stuff, too, because you can’t have the slurry of low-level nuclear waste lying in a cave somewhere and have the Iranians show up and find it. That would be bad.”

Maggitti was rewarded for his service to the United States. He asked to witness the last French nuclear test in French Polynesia.

“They looked at me for a little while and went, ‘OK,’ and that’s what they did. They flew me out there. It was the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen in my life,” he said, pulling out his phone to show a picture of the cloud. The food, he added, was fabulous.

In November 2022, doctors found two tumors in Maggitti’s brain – probably, he said, the result of being exposed to so much radiation during his lifetime. They operated on one in the front lobe and reduced the pressure, which had led to some uncharacteristic behavior. The second is inoperable.

Maggitti has entered a hospice program and now signs his emails, “Counting down the days …”

“It is what it is, my friend,” he tells me.

Update: John passed away April 8 in the comfort of his home.