Bob Appel: Writer of Icons

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

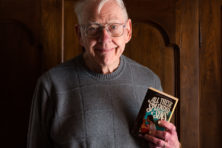

Bob Appel “writes” icons. Most people, in the computer age, would describe an icon as a small graphic representation of a program or file. But what Appel creates are very different — art depicting Christ, Mary, saints and/or angels. The tradition he follows — dating back at least 15 centuries — is based on the Greek word eikonographia, “image writing.” And iconographers write an icon to tell a story.

Appel is a native Door Countian. He was born in Baileys Harbor, where his great-grandparents, Jacob and Henrietta Appel, were among the first six families to settle. Walter Zahn, the blacksmith, was his uncle, and Willard Zak, the barber, was a first cousin.

In high school, Appel considered becoming a Methodist pastor, but he majored in education in college and came back to Door County at age 20 to teach for 30 years in the Fish Creek, Wildwood, Liberty and Baileys Harbor elementary schools. Although his college major was education, he minored in art and “always painted a little.”

In retirement, Appel became passionately interested in religious icons. Fifteen years of intense research and study have included retreats with three outstanding iconographers who helped to shape his second career. One of the instructors, Sister Maryam, a Franciscan nun, made her students promise that they would never sell an 8” x 10” icon for less than $350. That was to have a major influence on Appel, who does not create his icons to make money. If the value of an icon were based on the time required to complete it, it would be priceless.

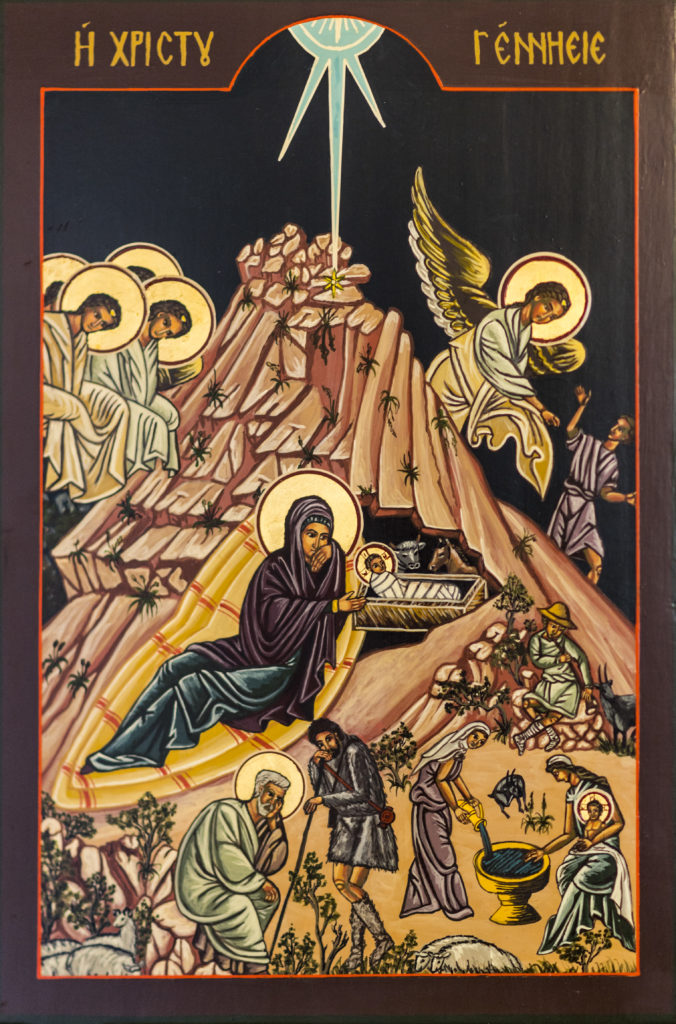

“The Nativity” by Bob Appel.

There are several stories about the origin of icons. One is that St. Luke, the author of the gospel, created the first icon of Mary and the Christ Child. Another, called “Not by Human Hands,” suggests that after St. Veronica wiped Jesus’ face with a towel during his crucifixion, the image of his face appeared on the towel.

Appel says that some Protestants (he is Lutheran) mistakenly look at icons as something that people pray to. Rather, he says, Solrunn Nes, a Norwegian iconographer and the author of The Mystical Language of Icons, has what Appel believes is the perfect definition: An icon is a physical sign of a divine presence. And it is to this presence, not the icon itself, that prayers are directed.

Prayer is also an integral part of an icon’s creation. There is prayer for beginning an icon, prayer throughout the process, and prayer upon completion. It is directed to God, who Appel says inspires every icon he writes, and for those whose prayers will later flow through the icon. Often an icon is created with a particular recipient in mind.

The process begins with the preparation of a board, which may be small or wall size. Appel often works with 8” x 10” boards and, because the process is so time-consuming, prepares a dozen or two at a time. First comes about 10 layers of gesso, a primer similar to a very thin white acrylic paint. Each layer is sanded after it dries. A layer of cloth is embedded, followed by another 10 to 15 layers of gesso with constant sanding until the surface is perfectly smooth, like dull glass. Two additional weeks of drying are required before writing the story with paint can begin.

Although older icons were usually done with egg tempura, Appel, like most modern iconographers, uses acrylics. An icon tells a story through its design and the figures portrayed and also through the colors used. For example, red represents humanity and blue divinity. Christ is shown in a red garment under a blue robe, representing the fact that he was born a human but became divine. Mary’s clothing is reversed — a blue garment under a red robe, indicating her divinity as the mother of Jesus, who then became part of the world.

Appel adds many fine details to his work, including this pearl inlay on “Mother and Child.”

It is traditional for iconographers to copy the work of earlier artists, although some do original work or adaptations. For example, a recent commissioned icon Appel completed, his 109th, combined figures from two earlier pieces. Because many people cannot afford the minimum price he promised Sister Maryam he would charge, he has given away more than half of his work. The money from any icon he sells is used to buy more materials.

Many galleries do not carry icons, which they classify as reproductions. Although Appel manages the art gallery at Coventry Care, the free medical clinic in Sister Bay co-founded in 2013 by his wife, Dr. Joan Traver, his work is not displayed there because no item in the gallery sells for more than $100. An exception is the show he holds each Labor Day weekend, with half the profit from the sale of any icon going to the medical clinic.

Appel has lived in Ellison Bay since his return to Door County in the mid-1960s. He has deep roots on the Green Bay side of the peninsula, too. His mother’s family goes back five generations there, to ancestors who were part of the second wave of settlers to arrive. Because there was illness on their ship, they were not permitted to come ashore in Ephraim, but were rerouted to Eagle Island, where Appel’s great-great-grandfather, Hans Hanson, died and is buried.

Appel said the theme of every icon he writes is chosen by God. This feeling was never stronger than about five years ago, when he had a strong urge to research St. Margaret, Queen of Scots, who died in 1093 and was canonized in 1250.

“As I was reading about her family background,” he said, “I couldn’t put my finger on it, but names began to sound vaguely familiar. I finally dug out our family tree and discovered that my paternal grandmother, whose maiden name was Lyman, was a direct descendant of St. Margaret’s father-in-law, King Duncan I of Scotland, famous for being murdered by Macbeth in Shakespeare’s play.” Shakespeare took a bit of artistic license, as Duncan actually died in battle during a civil war waged by Macbeth, his first cousin.

Those interested in Appel’s work may write to him at 11219 Frontier Road, Ellison Bay, WI 54210.