Coming Home: What Brought One Young Person Back to Door County

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Over Christmas break hundreds of Door County high school graduates came home to visit family and friends. For most of them, such short stops will be their only relationship with their hometowns for decades to come.

Door County, like so many of America’s rural communities, is getting older, a trend that puts its economic future in jeopardy and is changing the balance of its small towns.

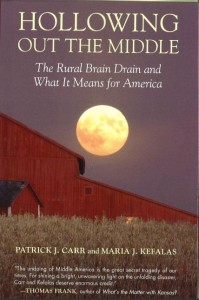

Hollowing Out the Middle, the new book by Patrick Carr and Maria Kefalas, has sparked a conversation about how to save America’s small towns and how we educate our youth.

One illustration of the rapid aging and shifting demographics can be found by looking at high school enrollment numbers. Since 2000, the four mainland high schools have seen enrollment decline by 202 students, a loss nearly equal to the size of Gibraltar High School. Look at K-8 enrollments and the picture is bleaker. Both Gibraltar and Sevastopol schools expect high school enrollment to fall below 180 within a few years, and likely lower.

What does that mean? Young adults are not staying or returning to Door County to raise a family, and while it’s an issue that has been batted around forums and barstools for years, it isn’t unique to our peninsula.

Husband-and-wife researchers Patrick Carr and Maria Kefalas released a book last fall based on the study of one small Iowa town grappling with the same problems. In Hollowing Out the Middle: The Rural Brain Drain and What It Means for America, they sought to find the answers to two primary questions.

“We wanted to know of young people, when you finish high school, do you stay or do you go? And if you go, do you come back?” said Carr, whom I interviewed by phone from his office at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, where he is associate professor of sociology. “We quickly realized that this issue is much bigger than one town.”

Carr and Kefalas interviewed hundreds of graduates from the town they call “Ellis, IA” (they don’t site the town’s real name) about why they chose to leave, stay, or return and the influences in school and community that led to that decision. Reading the results will sound familiar to anyone who has grown up and faced the same decisions in Door County.

Rachel Willems, who returned to Door County two years ago after earning her degree at the University of Minnesota, works at her desk in the winter home of the Ephraim Visitor Center.

The authors put graduates into three categories – Stayers who graduate high school and enter the local workforce or tech schools; Achievers who earn high marks then leave for top-flight universities and the big city; and Returners, or Seekers, who leave for college, maybe enter the workforce for a few years, then return home to raise a family or for a familiar way of life.

The efforts of small communities to revive their young adult base and local economy, Carr says, are usually misguided and inefficient. One of the critical mistakes they make is going after the Achievers.

“We have to stop the thought that says only the achievers can save us,” Carr says. “Small towns always go after the high flyers, but with the vast majority of achievers, once they’re gone, they’re gone. While we’re focusing on them, we’re missing all those that do come back, and they are the future of your town. We have to think of ways to say, ‘we’re so glad you came back’ and invite them to lead.”

One of those Door County Returners is Rachel Willems, who graduated from Gibraltar High School in 2000. She headed to the University of Minnesota, and she didn’t expect to come back for anything more than a summer job and a family visit.

“If you would have told me in 2000, when I graduated, that eight years from now I’d be coming back, I’d have said you’re crazy,” Willems says. “You grow up with this mindset that there’s so much of the world you haven’t seen and you want to get out. You almost graduate with this chip on your shoulder, that you need to go. I’d say that’s what my attitude was, and it’s almost a bad attitude.”

Willems graduated with a degree in Journalism and Mass Communication in 2004, but found the industry cold in her first post-college job. After a year working for what she called “glorified day-care,” she had a “quarter-life crisis. I had spent all that money getting my degree, and I’m asking myself ‘Is this truly fulfilling for me?’”

She came home and moved back into her parent’s house and expected to spend a year or two as a waitress at the family restaurant, the Sister Bay Bowl. She felt defeated, like so many who return home after crossing the canal.

“The social dynamics of small towns lead to a lot of self-defeating practices,” Carr says. “You’re not a failure because you stayed or returned. Small towns are important. Ties are important.”

Door County Administrator Mike Serpe said that attitude leads to detrimental community self-esteem issues.

“You have the problem of making those who stay feel like second-class citizens,” says Door County Administrator Mike Serpe. “There’s a bit of an impression that if you stay here you must be a moron, and that’s not true. To work at Bayship, to be a welder, or a naval architect or to be a farmer – any of those skill sets are extremely complicated. You have to value what people do. The best and the brightest are not necessarily the ones with the most letters after their name.”

Willems gets to the heart of the issue.

“You can feel like there’s this stigma about people who don’t finish college and just like living here,” she said.

The timing of Willems return proved perfect. A month after coming home in January of 2008, thanks to a run-in with a friend at the restaurant, she applied for and was hired as the Ephraim Business Council’s tourism administrator. The year-round position puts her skills to work and challenges her, something she knows it’s not easy to find in Door County.

“I’m thankful that the community I live in has this position,” she says. “It wouldn’t exist in Minneapolis or Chicago. I’m delving into the industry like I would never do at a big corporation.”

Often overlooked in small towns is the value of hiring people who know the local landscape and have ties, an issue crystallized in a conversation I had with workers at Itasca Engineering in Egg Harbor last summer. My brother Dan works for the small company and said they were struggling to fill engineering positions.

“We could go after someone from the major engineering programs, but if they’re not from here it’s going to be hard to convince a 24-year-old kid to come to Door County,” my brother told me. “If we do, they’re not going to stay long-term, so we need to find people with ties here, who want to be here.”

Willems has a degree from one of the country’s largest and best universities, but she says that degree alone would not make her good at her job.

“I’m successful here because I’m local,” Willems says. “I can wrap my head around the fact that Friday night fish fries put me through college and recognize how important tourism is. I didn’t come in with the big city idea that ‘I’m going to change all you dumb small-town folk.’ There’s nothing wrong with small towns.”

Except the dearth of good jobs. Willems readily admits that the only reason she’s still here two years after coming home is because she found a good, challenging position.

“People can’t move up here because there aren’t the jobs,” she says.

Though she says the social scene leaves much to be desired for half the year – “once the snow falls it doesn’t hold a lot of mystery for young people” – she said a slight shift in mindset can get young folks past those problems.

“When I lived in Minnesota what would I be doing on a Friday night?” she asks. “I’d be going to a movie or a bar, which is pretty much what you do here.” She also said you have to find an outlet and step outside your comfort zone. “I moved one community south [from Sister Bay to Ephraim] and a whole new group of contracts and networking opened up for me. I needed this job to force me outside my routine.”

A job is the over-riding factor in deciding to stay, leave, or move into the community.

“If there are jobs available, you’re going to go where you can find experience,” she said.