Crossroads Debuts New Ida Bay Preserve Trail

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

The age and level of preparedness varied in the group that participated in the Inaugural Hike at Crossroads at Big Creek’s Ida Bay Preserve.

Two young boys, who looked to be around 10 years old, wore bucket hats and long athletic pants for protection. A man who lived near the property wore a long sleeve checkered shirt, suspenders, and a big straw hat. One woman brought trekking poles. I was one of two hikers in Chaco sandals, which served me nicely.

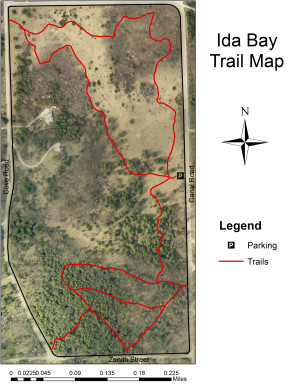

The Ida Bay Preserve is a 64.69-acre property located between Cove Road, Canal Road and Zenith Street and is less than a mile from Crossroads’ Utah Street entrance. I followed Coggin Heeringa, Director of Crossroads, from the learning center entrance to the trail parking lot on Canal Road.

Hikers take to the new trail in the Ida Bay Preserve during Labor Day weekend. Photos by Coggin Heeringa.

The first part of the new trail winds through a prairie. The path is wide and mowed, and we walked three abreast. Our leader, Joel Kaminski, is a biology and wildlife research and management major at the University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point.

It is Joel’s second summer as an intern at Crossroads, and the trail is his project. As we walked along, Joel explained how he determined whether or not the trail would accommodate maintenance equipment, if its path would remove certain trees, or disturb native wildlife, and if it would showcase important natural features to visitors and hikers.

The trail is the effort of two summers. Last summer, Joel created a plant inventory and mapped existing and potential trails, and created a trial trail, marked with yellow flags. This year, he worked with Crossroads to clear the trail for public use.

Though the property that the trail runs through belongs to Crossroads at Big Creek, it is not connected to their main building or trails. The area, called the Ida Bay Preserve, was donated by the Nature Conservancy to Crossroads in December of 2014.

The trail that our group walked was the first created in the prairie area of the Ida Bay property, but others exist in the old-growth forest. Along on the hike were several neighbors who had lived near the property for decades, but had never had access to it, or had lost access to it.

“I used to ride horses in this area,” the man in the big straw hat told me. “And then I met a girl, and we rode horses together.”

Many community members remember the different transformations the Ida Bay land experienced, and as we walked, Joel explained the different natural and manmade changes to the land.

We stopped in a wooded area near a nurse log where he explained that the shallow soil and the tree’s proximity to the bedrock made it vulnerable in strong winds, and more likely to fall.

“Eventually this will be a mound,” he said.

The group continued to a field where housing for migrant workers was once located.

“There’s juniper here and I don’t think you would have juniper growing on its own,” Joel said. “I get the feeling this was a garden at one point, and it was right in the area where migrant housing was.”

One hiker found a remnant of an old cherry pail underneath the canopy of a maple tree, where Joel hopes to eventually build an outdoor classroom.

“There is evidence of an orchard here,” Joel said, “and we found evidence of apple trees as well.”

More dramatic changes to the land have taken place in the past 25 years. Previous owner Ida Bay willed the land to the Nature Conservancy in 1995. Prior to her gift, Bay built a large fence around the perimeter of the property.

At the time of its construction, which neighbors estimate to have been 20-25 years ago, the cost of the fence was $60,000 (according to the United States Bureau of Labor statistics, $60,000 in 1995 has the same purchasing power as $93,951.97 in today’s market).

Initially the fence was constructed to keep teenagers from partying on the property. This, Coggin says, was its only virtue. While the fence was effective at keeping teens out, it also trapped the deer population inside the area. For more than 25 years, the deer population grew in a confined space.

“Sometimes when they were scared they would run against [it],” Coggin said. “The neighbors hated it.”

Only when Crossroads acquired the land was the fence removed. After the removal of the fence, neighbors described a different scene: herds of deer, 30 or 40 at a time, crossing the road and leaving the property.

While the large number of deer has begun to balance out since the fence’s removal, their impact on the forest will be noticeable for decades.

“It was an ecological disaster,” Coggin said. She explained that visitors to the old growth forest always comment on its beauty, and the way the forest floor is not crowded by undergrowth.

This effect was created by the overpopulation of deer, who, over the years they were enclosed, ate each new generation of forest.

“A healthy forest has new generations,” she said.

Simply by removing the fence, the land has already begun to heal.

Joel hopes that eventually the Ida Bay trails he has begun will be united with Bay Cove.

“If that were to happen, we wouldn’t have to walk all the way up the street to get to Crossroads,” he said.

Joel has already worked the maximum number of hours allowed for his internship, mowing grass, clearing forests and pulling shrubs, but plans on staying an extra week at Crossroads to volunteer.

“I love it here,” he said.