Door County’s Aviation History: Coming! Coming! A Flying Circus!

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

The historic aviators of Door County were not unique in the sense that they were enraptured with the miracle of flight.

That was universal.

But they brought a relentless dedication and spirit that turned a few dirt landing strips into symbols of our community and gave us the opportunity to view the peninsula with new eyes from high in the sky.

Ephraim, Gibraltar and the Growth of Aviation

Had stunt pilot Jimmie Woodruff been successful at building the landing strip he wanted in Peninsula State Park back in 1925 to serve his resort, Hotel Ephraim, things might look a little bit different for northern Door County’s aviation scene today.

After all, things didn’t turn out so well for Woodruff during the next few years. He sold the resort, where the Ephraim Condominiums stand today, after the Department of Natural Resources decided an airport wasn’t in their master plan.

A few years later he was charged with fraud and larceny in Green Bay, when he posed as a diamond salesman and promised to sell a diamond ring for a local jeweler. The story goes that he took the ring and gave it to Mary Moeller, the owner of De Pere’s Union Hotel at the time, to hold as collateral for $1,200 he owed in hotel bills. When he returned claiming he had a buyer for the ring that wasn’t his in the first place, Moeller gave it back to Woodruff and he made off with the ring and the unpaid bills.

Alas, “Jimmie Woodruff’s Flying Circus” may have taken its last ride, but Woodruff had high hopes for northern Door County’s role in aviation and the tourism industry.

“My aim is to advertise the town, and not only my own hotel,” Woodruff told the Door County Advocate in May 1925. “The chief thing is to get people here.”

That aim was reborn in the 1940s when the Ephraim and Fish Creek men’s clubs lobbied the adjacent municipalities to create what is now the Ephraim-Gibraltar Airport.

“The new Ephraim-Fish Creek Airport… will be ready for use in the very near future, as a result of work underway this spring, and is looking forward to a very busy tourist season,” the Door County Advocate wrote on April 26, 1946.

At the time, the thought that an airport would boost the tourism industry was universal. There were thousands of young men returning home from WWII as trained pilots, entering a booming economy where they had money to splurge on what was then a cheaper hobby. Door County’s reputation as a tourism hub had reached the ears of Chicago, but construction on the national interstate system would not start for another ten years, so the drive was significantly longer. Meanwhile, a small aircraft from Chicago could touch down on the peninsula in little more than one hour.

Photo by Len Villano.

Today, that tourism draw might be overstated.

“I think it’s a bit of a stretch,” said Brett Lecy, commercial airline pilot and member of the Ephraim-Gibraltar Airport Commission, when asked about the airport’s role in the tourism economy. “It’s not marketed. It’s not advertised.”

But Dick Knapinski, director of communications for the Oshkosh-based Experimental Aircraft Association, emphasizes the role of a small airport like Ephraim-Gibraltar in bringing people into the area.

“A number of your visitors, knowing there are good airports, will take that opportunity to fly in and enjoy what you have to offer up there,” Knapinski said. “People can come from Chicago, Milwaukee and suddenly it’s not a five-hour drive anymore.”

The Ephraim-Gibraltar Airport has a van parked in the lot and some bikes available for those who just drop in for the day, but Lecy said they don’t have a logbook to determine how many people are flying in and where they are coming from.

“The airport is staffed only on the weekends,” Lecy said. “There’s no way of telling what kind of trickle down occurs.”

The best glimpse we have into the tourism value of the airport is a 2008 economic impact report completed by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, and the numbers wouldn’t impress any tourism marketer or workforce economist — the airport generated the equivalent of three jobs and around $300,000 in economic output across the county.

Airport officials have shied away from the idea of expanding the airport to handle larger planes or marketing the airport to regional aviation hobbyists. Lecy said the Ephraim-Gibraltar Airport is one of a handful of airports in the state that make a profit, if only just a few thousand dollars each year.

“If we’re not a taxpayer burden why not just leave it the way it is?” Lecy said. “When you market the hell out of it, then there’s a fine line with the neighbors.”

He added that the airport receives approximately $150,000 in federal grants annually for improvements.

“That airport is really attractive, for some reason, to the FAA [Federal Aviation Administration],” Lecy said. “Geographically, logistically, it’s an important airport.”

When he hears Black Hawk helicopters flying over his Fish Creek home, Lecy packs the kids in the car to watch them run training exercises out of the airport.

But Ted Borny, Public Affairs Officer for the Coast Guard’s Traverse City Air Station, downplayed the significance of Ephraim-Gibraltar, admitting that he had to look up where it was upon hearing the name.

“I would not consider it strategically important or an airfield that we value any more than any other airfield,” Borny said.

The airport could have been an important fueling station for flights into Lake Superior until the air station got new helicopters with much better fuel efficiency last year, Borny said.

Knapinski said that because all of Door County north of the Sturgeon Bay Ship Canal is essentially an island, airports provide another transportation option in an emergency or serve as an economic asset for some rural businesses.

“The small airport network is absolutely essential as part of the transportation system,” Knapinski said. “It’s part of the economic engine. You have to look at an airport as you would look at good highways for trucks or good rail service. It’s all part of transportation infrastructure that in total is very important.”

Today, the airport lies relatively quiet between Ephraim and Fish Creek, welcoming the few aviation aficionados to its runway.

“We had a couple of instances when a group of old airplanes came in,” Lecy said. “It was an airshow group and they were practicing. There were these old, loud Russian Yaks [the Yakovlev Yak-9 was a single-engine fighter aircraft used by the Soviet Union in World War II] and we got so many complaints that day. You have to be sensitive to that.”

The days of Jimmie Woodruff’s Flying Circus sending planes into tailspins over Eagle Harbor and parachuting out in front of thousands on Ephraim’s shore are over. And perhaps that’s not so bad after all.

An Airport for the Land of Cherries

Wisconsin’s favorite peninsula is very much a drive in, drive out locale, and that’s just fine. Just know that with all that driving in and driving out, there’s a lot of driving past the 61 hangars and two runways at Door County Cherryland Airport just west of Sturgeon Bay.

One could spend many years living in Door County unaware that Cherryland Airport even exists, perhaps wondering why it even exists at all. This is an area known for its family businesses and boutique restaurants. It’s not exactly begging for private, chartered aviation.

Or is it?

Back in the 1920s, Door County shouted emphatically for planes to arrive. Flying as a pastime was young at the time, but was catching on in the Midwest’s biggest cities, and tourism dollars were at stake.

From a front page editorial in the May 25, 1928, issue of the Door County Advocate: “[Door County] cannot afford to lag behind in the establishment of an airport for the new mode of transportation.”

The argument focused on potential, and mainly that Door County wasn’t living up to its own. Oconto County had an airport and was flaunting it. Manitowoc had plans for its own, and down in Kilbourn (now known as the Wisconsin Dells), a local airport had recently been created. For Door County to compete, it needed an airport.

The timing of that editorial was prescient. Karl Reynolds, when he wasn’t too busy handling operations at Reynolds Preserving Co., helped create one of the county’s first airstrips on his family’s orchard land near the Sevastopol Town Hall. Reynolds set his gaze on the 1928 Cherry Blossom Festival, held the weekend after that Advocate editorial, in which thousands of tourists would be visiting the area. He wanted them to see Door County as much more than just road accessible. He called his airstrip Cherryland Airport. The blooming flora was just icing on the aviation cake.

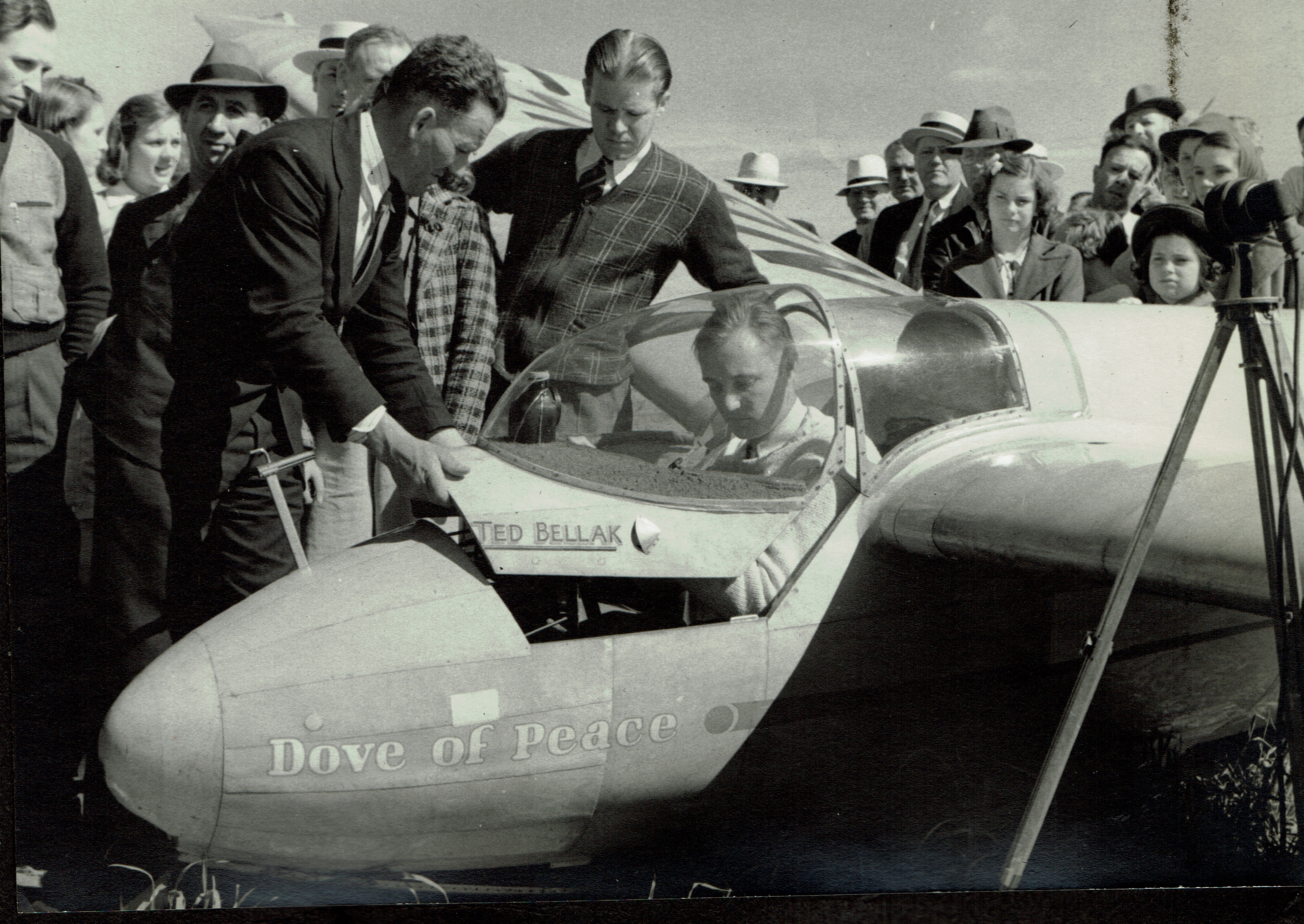

Rolfe Olsen lowers the hood on Ted Bellak’s “Dove of Peace” glider in June 1939. Bellak flew from Sturgeon Bay across Lake Michigan in his glider after cutting it loose from a plane that had brought him to an altitude of 16,500 feet. Photo by Wilmer Schroeder. Photo courtesy of Roger Schroeder and the Door County Historical Museum.

Reynolds picked a great weekend, as the festival was a hit, according to They Wanted Wings: A History of Door County Aviation. Pilots offered short, looping, $5 rides for anyone interested. In the span of a few days, more than 10,000 visitors were made aware that Door County was now a viable aviation destination.

By the time the 1929 event arrived, Reynolds had convinced not just vacationers, but also many local business owners that a better future existed through a county with an airport.

Although the proximity to the Great Depression was ominous, aviation in the county was well on its way. Also in 1928, a pair of runways were developed on Washington Island to serve as a last-ditch solution for citizens who feared winter storm isolation. Ephraim and Sister Bay had long been considered as possible third options for air strips as well. But Cherryland Airport was where future growth was most imminent, and airstrips on plowed orchard land would not suffice.

“Bow” Augustine helps load a shipment of cherries into Jack Hadden’s airplane in May 1940. Photo by Wilmer Schroeder. Photo courtesy of Roger Schroeder and the Door County Historical Museum.

The 1930s saw a few things happen: the first privately owned plane in the county arrived, a local chapter of the National Aeronautical Association (NAA) was created, and, finally, a push began for a paved airport adjacent to Potawatomi State Park, nestled along County Road C. When the county voted against the location in 1939, the NAA chapter responded in the most effective protest imaginable: they made the airport themselves, leasing the land and constructing the airport only as they envisioned. Members of the chapter went so far as to dismantle a hangar in Kewaunee, drive it north and reassemble it in Sturgeon Bay. As the Reynolds family backed off hosting flights into their precious orchard land, the new airport took on the old name. Then, in May, 1943, after years of operating on its own and now under the pressure of wartime agendas — the Door County board finally voted to purchase the already functioning airport. It is on that same plot of land where Cherryland continues today, in modest Door County fashion, managed by the cool hand of Keith Kasbohm.

Kasbohm is 59 years old and has been running the general aviation entity as a county employee for 29 years. As one of just a handful of people who work there full-time, he wears many airport hats to maintain safe landing and takeoff conditions, checking light fixtures and fuel pumps. If it’s happening at Cherryland, Kasbohm knows about it.

In the summertime, he’s cutting acres and acres of grass, but his position is perhaps never more important than in the winter. A two-inch snowfall normally takes him (and another employee) a full day to clear airport grounds. It’s a meticulous process that involves stopping a plow every 75 feet to avoid damaging runway lights. How about that 30-inch record snowfall from this spring? That took Kasbohm all week.

Businesses like Therma-Tron-X, which uses the airport constantly, don’t have all week. Either the snow is plowed in Sturgeon Bay or they take their business down to Austin Straubel in Green Bay. Kasbohm made it work, plowing temporary action ways within the runways to get the company on its way.

“That was great,” said Greg Goins, the 56-year-old chief pilot at Therma-Tron-X (TTX). The custom paint system manufacturer is likely the airport’s most frequent user, conducting almost all its business travel through Cherryland. It owns three planes and will fly its employees — from engineers to sales teams and electricians — wherever demand exists. During any given week, that destination could be Tomah, Wisconsin, or as far as Decatur, Alabama.

Goins typically flies work crews out on a Friday, returning on his own, and then picking that crew back up 10 to 12 days later. In mid-May, his work travel was a quick jaunt to Indianapolis. Just two hours after leaving their Sturgeon Bay homes, company employees were in Indiana. One day before that, one of his junior pilots took a crew to Florence, South Carolina. “He took off at 6:30 am and he had them there two hours and fifteen minutes later,” Goins said. “You just can’t do that with the airlines.”

Wisconsin Central Airlines demonstration ride on Oct. 17, 1947. Left to right: Howard Shaw, Charles O. Hansen, Dan Austad, Felix DeBroux, Enar Ahlstrom and son, Dan Dorchester, Cyril Virlee, Russell Austad, Bill Austad, Leo Stonrman and Karl S. Reynolds. Photo courtesy of Dan Austad. Photo by Chuck Krause.

Therein lies one of TTX’s highest priorities: avoiding airlines. To have Cherryland Airport at its disposal is the ultimate efficiency boon. “People don’t want to fly into Green Bay,” Kasbohm says. “It’s an hour drive. They want to fly to the doorstep.”

For TTX, it’s fly where you please, when you please. If a snowstorm hits, pray that Kasbohm is around. (He almost always is.) It doesn’t hurt that TTX president Brad Andreae occasionally pilots some of the planes himself, as does his son.

While Therma-Tron-X might be the airport’s most frequent user, there are many more, including the shipbuilding industry. In total, the airport conducts approximately 10,000 arrivals or departures from on-site aircraft per year, and 12,500 for off-site aircraft. That’s your sign of tourism. June through September are the popular months, to no surprise, and by Kasbohm’s estimate, tourist flights make up about 75 percent of the airport’s summer usage.

“You see the aircraft come in and guys unload their golf clubs, so you know they’re using the golf courses in town,” he said.

But what is it actually like to “come in” to county from the sky? Could there possibly be any better way of arriving at Wisconsin’s favorite peninsula?

Approaches often take passengers out over the canal, offering a taste of Sturgeon Bay, a peek out to Lake Michigan and then quickly over the treetops of Potawatomi Park before landing nearby. Goins, who lives and owns his own airstrip in Two Rivers, and who has flown all kinds of planes all over the world, tends to savor that Cherryland arrival on his return flights. One recent landing stayed with him.

“It was a Friday. I was coming in from Florence, South Carolina, and there was [bad] weather just south of us. I popped out to the side of the weather and I’m looking out over the whole peninsula from Kewaunee northward. You could look over toward Green Bay. You could see the whole peninsula all the way to Washington Island. The visibility was spectacular. It’s really a pretty sight.”

Sounds a lot like the Door County we know, right? Just from a completely different angle than you and I are used to.

An Island Only in Name

It is hard to imagine that two finely mowed grass strips nestled in the northwest corner of a generally quiet island could instill such reverence in any group of people. But mention Door County in front of an aviator and the conversation will quickly turn to Washington Island.

“One of the favorites of people here in the Fox Valley is Washington Island,” said Dick Knapinski, senior communications adviser for the Oshkosh-based Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA). “From here in Oshkosh, within an hour you can be up in Door County… and land at Washington Island.”

Karly’s Bar and Nelsen’s Hall have probably served their share of $100 hamburgers, which refers more to the cost of fuel than the cost of food for a pilot that flies in for lunch.

“Washington Island is kind of cool from the standpoint, it’s just two grass strips yet it’s open year round,” said Brett Lecy, Fish Creek resident and commercial airline pilot. “I don’t know how they do it.”

One of the ways they do it is by tying their annual Fly-In Fish Boil to the EAA’s AirVenture event in Oshkosh each July. The island’s fish boil takes place on the Saturday of the 10-day event in Oshkosh.

“They do one fundraiser a year and it’s right around the air show at Oshkosh,” Lecy said. “With the aviation world at Oshkosh, a lot of people like to take day trips and fly in and looking at a map and seeing that island with an event going on just is a magnet.”

Oshkosh’s AirVenture brings in more than 500,000 people and 10,000 planes to the state each year and Washington Island just needs a small slice of that to support itself.

“They get loads of airplanes in there and that one fundraiser funds the entire upkeep of the year on Washington Island,” Lecy said.

The airport’s fame among pilots could stem from its long history. First operated privately beginning in 1928, the town bought the land in 1939 to keep the airport running, making it the first municipal-owned airport in Door County.

In the early 20th century, when a ferry across Death’s Door was not as reliable as it is today, the airport played a big role in safety and access to the isolated island.

“Of special note was the arrival of the airplane at 8:30 on schedule time while the boat ferry was held up from one trip on account of the heavy seas from a storm the night before and telephone connections from the same cause were broken until noon,” wrote the Door County Advocate on Aug. 24, 1928. “Thus the airplane for half a day was the only means of the island’s communication with the outside world.”

The airport’s role in connectivity to the mainland is well documented. In 1968 the New Year’s baby arrived, “by stork — if you can call a four- place Cessna a stork.” In 1947 Dick Bjarnarson escaped death via an airplane to the hospital after a hunting accident.

Knapinski still emphasizes the role of small, rural airports in the nation’s transportation network.

But there’s a certain magic to small aircraft flight that Knapinski and Lecy embrace even more.

“You get to see our state, our region in a whole new way and see the geography from above,” Knapinski said. “I’ve seen it while driving but to see it from above is a whole different perspective.”

“It’s that freedom of spontaneity to be able to think outside the box and do something you wouldn’t normally do,” Lecy said. “You can get in an airplane and you can have breakfast in Michigan and you’ll be there in 20 minutes. It’s the freedom.”

World War II, Top Gun and 9/11

The precipitous drop in the number of pilots, around 210,000 in the past 30 years, is the talk of the aviation industry, particularly as the popularity of flight continues to take off.

Boeing estimates airlines will need 637,000 new pilots in the next 20 years to meet the demand for air travel. There are as many theories on the nature behind the decline as there are planes leaving O’Hare every day, but there are a few watershed moments that played a part in the country’s loss of pilots.

“One of the major reasons is demographics,” said Dick Knapinski, senior communications adviser at the Oshkosh-based Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA). “A lot of the people who learned to fly right after World War II in the post-war boom … are now aging out of active participation in flying. They are up in their 80s and they’re just not flying anymore.”

In the middle of the 20th century, the military functioned as a pilot incubator. Recruits didn’t have to pay for their training and many pilots spent just a few years in active duty before returning home and continuing flight as a hobby with small aircrafts, commonly known as general aviation (GA).

“The military pool is dwindling and now more military aviators stay in a career as opposed to just a few years and then transfer to airlines,” said Brett Lecy, Fish Creek resident and pilot for Delta Airlines.

“Everybody involved in GA right now, they’re all old guys,” said Lecy. “There’s very few women, there’s very few young people and it’s sad to see.”

GA is just starting to lose its baby boomers, but that population has already aged out of the commercial airline scene. Federal law requires commercial pilots retire at 65 years old.

In the post-war period, pilots were also revered in a way that put the profession near the highest rung of the social ladder. Until World War II, flight was primarily reserved for the military and those who served enjoyed a long period of glory and prosperity.

Commercial aviation and passenger planes exploded after the war, but it was still amazing to see a plane in flight for folks on the ground.

“I remember when I was in the early ’40s, every time a plane went by everybody stopped what they were doing, farming or whatever, and looked at the plane because it was unique,” said Myrvin Somerhalder, member of the Ephraim-Gibraltar Airport Commission.

The 1950s and ’60s is commonly referred to as the “golden age of travel.” Travelers dressed up before heading to the airport. There was plenty of legroom and some reports tell of roast beef delivered by a stewardess sliced right in front of you at your seat. Pilots took on celebrity status.

Lecy said the popularity of flight was further buoyed in the 1980s with the release of Top Gun. He laughed as he said this, but not because it was a joke.

“That was my generation, big time,” Lecy said on the impact the movie had on his career goals as an impressionable teenager.

Lecy began training in Appleton when he was 17 before going to college for aviation at Southern Illinois University. A few years after getting his degree, terrorists hijacked four planes and crashed them into New York’s World Trade Center, the Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania, killing 2,996 people.

“When 9/11 hit, that flight program… so many people dropped out,” Lecy said. “They thought there’s no way. This is not a viable career anymore.”

A 2003 article in the New York Times describes tough times for flight schools in the aftermath of 9/11, with more than 50 schools closing in Florida within two years of the attacks. The Times said Florida trained about 20 percent of all the pilots in the world.

“9/11 was a huge thing for all of aviation, especially in the United States but also around the world,” said Curt Drumm, former flight instructor and president of Lakeshore Aviation in Manitowoc.

Drumm said new regulations on airlines and pilots that came down after 9/11 and another 2009 plane crash in New York raised the bar even further for aspiring pilots.

One new regulation often pointed to as the biggest hurdle for pilots is a 2013 rule from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) increasing the number of hours co-pilots must train in the sky from 250 to 1,500.

Because co-pilots serve as an assistant to the pilot in command, who is very highly trained, Drumm said the added time was a “knee-jerk reaction” from Congress.

“It dried up the whole supply chain of pilots,” Drumm said.

The added flight training comes at a big price to aspiring pilots and things didn’t get any easier when the global economy collapsed in 2008, making an already expensive hobby or career choice even less attractive.

“Flying lessons are expensive and it kind of fell apart,” Drumm said.

Even in the stronger economy of today, flight has not gotten any cheaper.

Lecy said the cost of maintaining and flying a 1949 Cessna 140, a family heirloom that he owned with his wife, was simply not worth it. They recently sold the plane.

“It’s expensive,” Lecy said. “I think we flew two hours in a year and every year you have to do annual maintenance and that’s an expensive gig.”

In the pilot shortage, Drumm said smaller airports and regional airlines are the first to go.

“The big guys are sucking all the pilots out of the smaller regional carriers and the regionals are sucking them out of the charter and flight schools,” Drumm said. He is currently trying to revive the defunct Midwest Airlines by acquiring planes from an airline in Wyoming that went out of business due to the pilot shortage.

But there is some scattered hope in the industry.

Knapinski said the number of new students in flight schools has increased, if only modestly, the past few years.

Pilot salaries have turned around too. For years, wages hovered around $20,000, a meager fraction of the cost for education and training. Now, Drumm said even regional airline pilots start between $60,000 and $70,000.

But scattered hope has done little to soothe people in the industry.

“You’re working with a finite set number of participants,” Knapinski said. “It’s not like an amusement park where you can try to grow your audience.”

“There’s a lot of concern in the industry,” Drumm said.

Lecy has a hard time being optimistic about the future of the industry, but he’s holding out for the help of Goose, Maverick and the sequel of Top Gun, slated for release in July 2019.