Door County’s Fading Farms

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

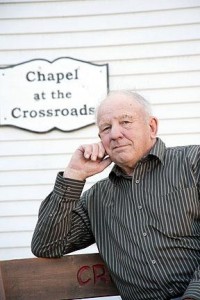

George Evenson was born on his family’s farm on County P in Sevastopol and named, he says, after George, the family’s plowhorse. For most of his 81 years, he was involved with the dairy industry, and probably knows more than almost anyone else about the industry’s history in Door County.

I spoke with Evenson over a September breakfast at McDonald’s, during which he talked about the industry’s beginning on family farms, its glory days, and its evolution into today’s large-scale mechanized operations.

The first settlers had to cut timber to clear the land, and it was hard, slow work – probably just an acre or two a year. In the meantime, cows could graze on the lush grass. Every family had one or two to provide milk and calves. Farm wives separated the cream and made butter to sell. By the 1870s and ‘80s, the cow population had grown to the point that most people had extra milk to sell, and cheese factories sprang up. At one point, the Town of Sevastopol had 10 factories – and 10 taverns. “The taverns lasted,” Evenson says, “but the factories did not.”

For 20 years or so after the turn of the century, the dairy industry continued to expand. The typical herd was 15 or 20 cows, and farmers built huge barns to hold enough hay to feed them over the winter. These barns, once a distinguishing feature of Door County, are nearly gone today. In their heyday, the late Bernal Chomeau, who had a summer home in Ephraim, captured every one of them. This treasure, the record of a bygone way of life, is stored in the Door County Archives, an annex behind the Door County Historical Museum.

About 1920, the University of Wisconsin began a major effort to improve the dairy industry by encouraging the construction of silos. This increased the capacity for storing feed, and corn chopped for silage was also more nutritious, leading to higher butterfat content. This was the era when Horseshoe Bay Farms, south of Egg Harbor on Bayshore Drive, was developed as a model dairy farm with strong input from the University of Wisconsin. The barns provided more comfortable living conditions for about 60 cows. It was an omen of the era of big dairies on the horizon.

Artificial insemination began in 1947, making it possible for even the small dairy farmer to develop a herd that gave milk high in butterfat. Within just a few years, the average annual butterfat production doubled from 400 pounds per cow to 800 pounds. (By the way, the test – still used today – for measuring butterfat was developed in 1890 by Stephen Babcock, an agricultural scientist at the University of Wisconsin. Prior to that, farmers had to wait for cream to rise to the top of the milk and estimate the percentage.)

Evenson remembers the next revolution in dairying that came in 1948, when a group of farmers formed the Lake to Lake Dairy Cooperative. The group built two big plants and assured dairymen of a better price for their milk. To this point, milk had been used for cheese and condensed milk. Now there was the opportunity to produce Grade A milk for bottling and ice cream. This required higher standards for the way dairy herds were housed and milked. The cooperatives also bought Grade B milk, but the price was lower.

The 1960s brought dramatic changes that affected not only the dairy farmers, but also the social aspects of their communities. In earlier days, 80 acres could support an average dairy herd. Now mechanization brought tractors, milking machines and other modern equipment, enabling one man to do the work of 10. It meant that more land – 200 to 300 acres – was needed to support herds of up to 500 cows. It also meant the death of the neighborhoods where everyone knew everyone else and shared the work of threshing and cherry picking. (Over the years, nearly every dairy farmer had planted eight or ten acres of cherries to boost the family income.)

“Those days of shared hard work were fun, almost like parties,” Evenson says. “Our granary had a hardwood floor for dances, and there was even a special place for the band. That all changed. Farmers who were successful continued to expand, and the little guys who couldn’t compete any longer either sold out or died off. People don’t live close to one another anymore. It’s impacted the schools and churches, too. In the square mile in Section 14, there were 20 kids in school when I was growing up. Now there are none, and no prospects of any. I’ve seen confirmation classes at the church shrink from 20 children to one or two.”

Evenson was a dairyman for decades, surviving the many changes in the industry. When he retired in 1997, he had a herd of 60 to 70 cows. It’s symbolic of the times that a once-thriving dairy has been reincarnated as Cherrydale Farm, where Amy Stich, one of Evenson’s three daughters, raises and sells organic vegetables.