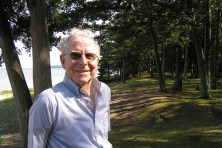

Hank Eckert: Door County’s Member of ‘The Greatest Generation’

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

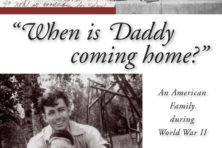

Tom Brokaw described them as “the Greatest Generation, who grew up in the United States during the deprivation of the Great Depression, and then went on to fight in World War II.” FDR said, “This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.”

There aren’t too many of them left now, but Door County can claim one of the best.

How appropriate that Henry “Hank” Eckert, destined to be a hero, grew up in the log cabin his father built on County F near Fish Creek. His leadership skills were evident early. He was class president all four years at Gibraltar High School, and he and his sweetheart, Donna Berns, were prom king and queen in 1938.

Encouraged by his coach, Horace Freeman, to attend college, Hank arrived at Ripon with $5 in his pocket. He played basketball and participated in ROTC, which paid $20 every three months. Working as a waiter in the dining hall covered the rest of his expenses. There was no question what the future held for young men in 1943. Two weeks after graduation, Hank was a 2nd Lieutenant in the army.

A short stay at Camp McCoy in southwest Wisconsin was followed by Officer Training School in Texas. On Aug. 10, 1944, Hank was one of 15,000 who shipped out of Boston, bound for Liverpool, England. A train ride took them on to Winchester. A week later, as part of the 95th Infantry Division of Patton’s Third Army, they crossed the English Channel to Omaha Beach. By then, months after the D-Day invasion, it was a secure military base, but months of prolonged, fierce battles to liberate the Lorraine region of France lay ahead.

Shortly after arriving in France, Hank volunteered for the “cannonball run,” patrolling the supply lines, searching for German positions. “The Germans were tough,” Hank told his grandson, Tom Birmingham, Jr., in an interview for a school project in 2002. “They had trenches and pill boxes and heavy fortifications.”

The Maginot Line was a zone of heavy defensive fortifications erected by France along its eastern border in the 1930s, but it was outflanked in 1940 when the German army attacked through Belgium. By the time American troops arrived, it was heavily fortified. The Siegfried Line was a defensive line built by the Germans, also during the 1930s, opposite and to the east of the Maginot Line.

Charles B. MacDonald, an officer in the 2nd Infantry Division, wrote in The Siegfried Line Campaign, “Some who have written of World War II in Europe have dismissed the period between 11 Sept. and 16 Dec. 1944 with a paragraph or two. This has been their way of gaining space to tell of the whirlwind advances and more spectacular command decisions of other months. The fighting during September, October, November and early December belonged to the small units and individual soldiers, the kind of warfare which is no less difficult and essential no matter how seldom it reaches the spectacular.”

It was certainly true in the case of Patton’s 3rd Army. Battles elsewhere in the European campaign received more notice than the brutal fighting along the Maginot and Siegfried lines in the Lorraine. Hank faced actual combat for the first time along the Maginot Line. Air support was almost nil. Torrential rain turned fields to muddy quagmires, making tanks unusable off-road. There was constant fighting for two months. Eighty percent of the men in Hank’s unit were killed or injured, including Hank’s roommate of six months, who lost his life there. Only 40 of the original 200 were left to fight, and by mid-autumn, replacements had largely run out. “The German soldiers were good,” Hank told his grandson Tom. “They had better equipment than we did and in some cases were better trained. Where we took ’em was in our spirit and determination.”

At some point during this campaign, Hank was injured and received a Bronze Star, the fourth-highest-ranking medal for bravery, heroism or meritorious service. The fighting was so intense that he’s not sure just which action it was for. In early December, he suffered broken ribs when he was blown 15 feet through the air by a German shell and landed on the side of a foxhole. It qualified him for a Purple Heart, but the fighting was so intense that no one had time to fill out the paperwork. Hank was taped up and sent back into battle. The enlisted man who served as his runner, taking information to other positions, was killed by a bullet that penetrated his helmet. Hank imagines the sniper was probably aiming for him.

On Nov. 15, the battalion’s objective was Fort d’Illange near Thionville, France, overlooking the Moselle River. It was held by a garrison of 1,500 Germans. Hank led five men in capturing a machine gun position outside the fort, providing a foothold from which a successful assault on the fort was launched the following day. For this, he earned a Silver Star for gallantry in action. (It’s the third highest combat decoration, ranking after only the Medal of Honor and the Service Cross.)

This was part of the allied forces’ drive to conquer the heavily fortified French city of Metz, a key to the success of the war. Hitler had declared it “a fortress to be defended to the last bullet.” The queen city of the Moselle region, Metz had withstood all attacks by military forces since 451 A.D – 1,493 years. With strong German resistance, it was finally captured on Nov. 22, and the last of the forts defending the city surrendered on Dec. 13. For their valor in this bloody campaign, the men of the 95th Infantry Division were nicknamed The Iron Men of Metz. After the battle, Gen. Harry L. Twaddle, the division commander told his troops, “In the hell of fire along the Moselle River and around the mighty forts of Metz, you proved your courage, your resourcefulness, and your skill.”

On June 20, 2014, Clifty Creek in Columbus, Ohio, was renamed in honor of the Iron Men. Francoise Leclercq, who lives in Metz, traveled to Columbus for the ceremony. She has made similar trips during the past 15 years to honor the American servicemen during their annual reunions. “The Iron Men of Metz are the reason why we are still there today,” Leclercq said. “In this country they have gotten some recognition. But in Metz, they are revered.”

After the capture of Metz, Hank’s unit was pulled back to rest and get badly needed replacements. Four truckloads of replacements arrived on Christmas Day, along with a new pair of boots for Hank, but there was no celebration. The division was called back to the front, along the Siegfried Line.

For the first time, they faced SS troops, a combat cadre who specialized in brutalizing and murdering individuals in territories occupied by the Nazis. “That’s where the Germans really fought!” Hank told his grandson. “Those guys never gave up. You couldn’t capture ‘em. You just had to kill ‘em.” He said the platoon he led tried to follow the Geneva Conventions, saying that no one waving a white flag or pleading for surrender should be killed. “Some of the older German soldiers surrendered easily when combat was heavy, but some of our troops shot anything that moved. This was against the rules, but I guess there aren’t really any rules in war.”

On New Year’s Eve, Hank volunteered for an especially dangerous mission, and his commander said, “Hell, no. I can’t afford to lose you.” Enlisted men were sent instead. The next day, Jan. 1, 1945, the commander was seriously injured, leaving Hank in charge of the entire company. As he and three other men raced across a field toward an 88-millimeter artillery gun, all of them were felled by shrapnel from a shell that landed just behind them. “It was unusual that we were all grouped together,” Hank says. “We usually spread out for safety’s sake. Maybe they thought I’d been lucky, so they wanted to be close to me.”

Hank’s luck nearly came to an end on that field. Shrapnel nicked his jugular vein and one of his vocal cords. “When you fall down like that, the first thing that comes into your head is to get back up,” he told his grandson. “I got up…and I could feel blood shooting out the side of my neck. I collapsed and couldn’t move or talk any more.” He was able to press his gas mask hard against the wound, easing the blood flow, but he knew if he didn’t get help, he wouldn’t last through the night. Because of the heavy fighting, the injured men lay where they fell for hours, until it was dark enough for them to be rescued. Hank was carried off the field to a shelter on a nearby German farm. A door ripped from a schoolhouse served as a stretcher, and he was loaded onto the hood of a jeep for transport back to the battalion aid station.

After a few days of treatment there, he was moved to Thionville, France, where he lay on a makeshift stretcher on the ground under a large tent, waiting to be loaded onto a French medical train headed to a large allied base in Cherbourg. Two months in a hospital followed. No planes were flying, so an English hospital ship took him to Southhampton. Hank says that ship had the best food, the best service and the best treatment he ever received throughout his military career. And this time, he did get a Purple Heart.

He underwent several surgeries during two months in an army hospital in Southhampton, then boarded a ship that was part of a convoy of about 30 vessels full of wounded GIs headed for home. On the third day out of Southhampton, a German sub attacked a destroyer on the outskirts of the convoy. The trip across the Atlantic took 12 days. “When we first arrived in New York harbor,” Hank says, “the Statue of Liberty turned up in the mist. Boy, did that put some gleam in our eyes!”

During two nights in the city, he and five other officers visited Jack Dempsey’s Broadway Restaurant, across from Madison Square Garden.

From New York, Hank was sent to a hospital in Louisville, Kentucky, where he had several more operations over five months and worked on regaining the ability to speak. Three pieces of shrapnel are still embedded in his neck, too close to his spinal cord to be removed safely. “The medical staff said there was no place for me in the Army,” he says, “and I was discharged.”

He returned to Door County and, in 1946, married his high school sweetheart, Donna Berns, whose older brothers owned a lumberyard in Sister Bay. Hank worked there for a few years, until President Truman appointed him as Sister Bay’s postmaster in 1950, a job he held for 30 years.

He was dedicated to his job and also to his family. Donna died of cancer in 1964, at 43, leaving Hank with four children, the oldest just 17. He raised them well and also devoted countless hours to the community he loved, serving at various times as president of the Gibraltar Board of Education, the Sister Bay Lions Club and the Peninsula Golf Association. (He says the Dale Carnegie course in public speaking was one of the best things he ever did, preparing him for all that public service.) Hank was a Boy Scout leader for 33 years, served as president of the Billy Weiss American Legion Post in Sister Bay and led the veterans who marched in the July 4 parade in Baileys Harbor for half a century.

A resident of Scandia Village since 2008, Hank will be 94 in September. His memory is sharp, and he’s proud to tell visitors about his many medals and other awards mounted in a frame. The six-month battle to liberate the Lorraine region, in which Hank participated, eventually cost about half a million military and civilian lives. Seventy years after he was wounded, his face still becomes sad as he thinks of the many comrades whose fate he never learned. His family had planned for Hank to participate in an Honor Flight to Washington, D.C. and a trip to visit the area where he fought in Europe, but back problems have made it impossible for him to travel so far.

Hank’s son, Steve, who served with the 3rd Marine Amphibian Forces in Vietnam, lives in Sturgeon Bay. His sisters are Anne Meyer, Menomonee Falls; Carol Franke, Sister Bay; and Linda Birmingham, who lives in the log cabin near Fish Creek where Hank and his siblings were born. There are eight grandchildren and a dozen great-grandchildren.

Hank is in a wheelchair now. He won’t be marching in the July 4 parade this year. But as you watch other veterans pass by, remember the words of Will Rogers, “We can’t all be heroes. Some of us have to stand on the curb and clap as they walk by.”