Door County’s Original Historian: Hjalmar R. Holand

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Few, if any, individuals who have called Door County home have led more interesting lives than Hjalmar R. Holand. His interactions with famous people, his world travels, and his prolific writings combine to form a remarkable life. And though he called America home for most of his 90 years, his Norwegian ancestry defined a large portion of his life.

Holand was born on October 20, 1872, on a farm called Salstroken on the shore of Lake Hemness in the southern part of Hِland in Norway. His father was a successful farmer who sold the farm in 1878, moved the family to Oslo, and bought two apartment buildings. For a brief time the family fared well, but poor investment decisions caused his father to lose the apartments, forcing him to take whatever handy work he could find.

Holand’s mother died two years later at the age of 50, so when Holand’s older brother, Anders, invited Hjalmar and his younger sister Helen to join him in America, Holand’s father cobbled together the funds to send the two to Chicago. Hjalmar was just 13 years old.

The ensuing years were often difficult as Holand pursued both work and education. He worked for and met Marshall Field in Chicago where he took high school classes at the YMCA. He attended Battle Creek College in Michigan for several years while working for Dr. J. H. Kellogg. But most of Holand’s years were spent in the role of itinerant bookseller, traveling throughout the region selling books door to door.

Hajlmar Holand’s Histories of Door County are the most important – if not entirely accurate – recounting of the peninsula’s early years.

The contacts he made in the Norwegian communities in Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota during his travels would ultimately provide the material for his first book, but Holand was always looking for new areas and communities to sell books, which led him to Door County.

As he noted in his biography, My First Eighty Years, published in 1957, “over on the eastern edge of Lake Michigan lay a long peninsula between Green Bay and Lake Michigan which now and then had beckoned to me. Not only its shape, but also its local names fascinated me. They were not all attractive, to be sure, as, for instance, Sevastopol, which was meaningless, seeing there were no Russians there. Fish Creek was plebian, and Europe Lake was a wretched misnomer, no matter what its shape or size. But most names were good – Sturgeon Bay, Egg Harbor, Ephraim, Sister Bay, Gills Rock, North Bay, Clay Banks, and Lily Bay. Especially did I like Ephraim because it had the flavor of old, patriarchal history.”

Holand arrived in Sturgeon Bay in late summer of 1898, having made the trip from Madison on his bicycle. After consulting maps at the courthouse, Holand became interested in the Ephraim area. Satisfied that he knew his way he set off on the “highway” north to Fish Creek on his bicycle, a trip where he observed that “apparently the county had not yet emerged from the early pioneer stage.”

It was on his second day in the county that he reached Ephraim, where he coasted down the last hill to the beach. “There it lay,” he wrote, “a charming little village, with every house painted white, against a background of bright evergreens on a steep hill behind it! Nowhere had I seen a village that could compare with it in beauty and location.” Sixty years later he still felt the same way.

While visiting, Holand became convinced that he needed to own his own land in the community, particularly somewhere across the harbor near the escarpment that so dominated the view. In expressing this desire he learned that there was, indeed, someone who might be interested in selling by the name of Ingebret Barlund, who owned 57 acres just around Eagle Bluff from the village in the area now known as Nicolet Bay.

After meeting with Barlund, Holand found that the property could be purchased but he would need time to raise the funds – $50 – in a month to complete the deal. Holand felt confident he could sell the books necessary to raise the funds in the allotted time, but it ended up taking five weeks. Barland now stated that he had changed his mind about selling but Holand was undeterred. He raised the offer to $75 and, when that was turned down, Holand raised the offer to $85 and tossed in that he would allow Barland to cut trees on the property for a full year. This time Barland accepted but Holand, being $35 dollars short of the agreed upon price, was forced to ask parson Gudmund Kluxdahl for a $20 loan and borrowed the additional $15 from the Sunday School kitty.

At last Holand had the funds and bought the 57 acres that is now a portion of Peninsula State Park. The deal done, Holand returned to Madison to continue his studies. While at the University, Holand met his wife, Evelyn, and also learned from professor William A. Henry, Dean of the College of Agriculture, that Door County was an excellent place to grow fruit trees.

As it turned out, Barland never harvested any trees during his year of being entitled to do so, thus Holand hired a local man to clear trees and blast stumps. Within a few years, the land satisfactorily cleared, Holand purchased 1,200 fruit trees (1,000 apple trees and 200 cherry trees, though he sold 100 of the cherry trees to Dr. Eames in Egg Harbor), which he planted in the spring of 1902.

His home was already built, a modest 20-foot by 31-foot structure with two rooms upstairs and three downstairs. The foundation of his home can still be seen in the state park.

By now, Holand had been selling maps for Rand McNally (primarily used as advertising premiums by purchasers) but he quit this work to pursue his writing. He was one of the founding members of the Norwegian cultural society and was elected the society’s archivist and historian. He took his appointment seriously and traveled to settlements throughout Minnesota, Wisconsin and Iowa, giving talks, enlisting new members, and – most importantly – collecting the stories and recollections of the early settlers in each community he visited. These interviews were eventually compiled into Holand’s first book, published in 1908, titled History of the Norwegian Immigration, published in Norwegian, with 622 pages bound in half leather and 50 portraits of old pioneers. The books sold for $2 each.

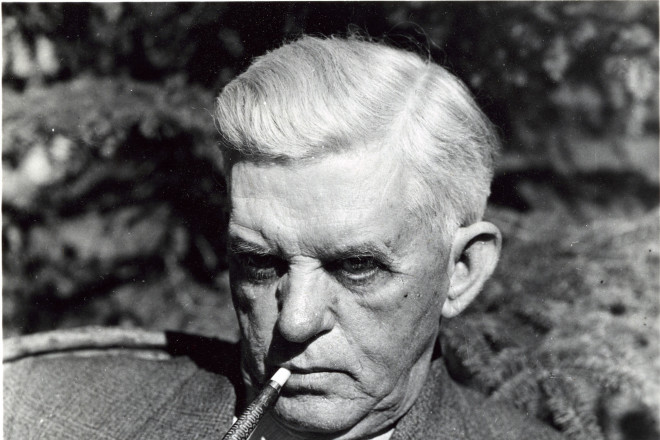

Hjalmar Holand at his homestead, which is now part of Peninsula State Park. Photo from the collection of Barb Olson.

In 1916, a representative of S.J. Clarke Publishing Co. approached Holand with an offer to write a history of Door County, which they would publish and sell. Holand had already been writing historical sketches for the local paper and, with an offer of $500 payment for the manuscript, readily agreed. Thus, History of Door County Wisconsin: The County Beautiful, a two-volume set was published in 1917.

The first volume concentrates on the actual history of the peninsula, beginning in 1608 with the arrival of the French up to the year of publication. The second volume features biographical information of early settlers on the peninsula, which Holand collected in much the same way he collected recollections and stories of Norwegian settlers for his earlier book.

“The book … came out on the date planned,” Holand wrote. The publishers were very complimentary and said it was the most complete county history they had ever published.

“It was indeed very complete,” he continued, “because I went through the town and county records to include every justice of the peace and constable that ever had office.”

Holand realized, however, that the very completeness of his two-volume set “detracted from its readability.” So he decided to write another book and the result was Old Peninsula Days, published in 1925. He expected sales to be rather limited for his slimmed down history so he printed 1,000 copies at his own expense. But much to his surprise the book was a success, “going through seven editions and about 12,000 copies” by 1957.

Holand played with the manuscript for Old Peninsula Days throughout his lifetime, rearranging chapters and adding new material. Following his death, a number of publishers reissued versions of Old Peninsula Days based on one or another of these editions. In consulting with Peter Sloma, owner of the Peninsula Bookman, a used and collectible bookstore in Fish Creek, and Kubet “Kubie” Luchterhand, owner of Caxton Books and Wm. Caxton Ltd. publishing, Old Peninsula Days has had between 11 and 13 editions, though some are exact reprints of earlier editions.

Through the years the accuracy of Holand’s Door County histories has often been questioned. To some extent this may be due to the lack of bibliographies and scarcity of footnoting in either history. Another factor is that Holand collected recollections from settlers and then organized them into a chronological sequence. Therefore a large portion of his two-volume history and certainly all of Old Peninsula Days is more accurately described as oral history rather than history in its strictest sense. As Sloma noted, “Holand liked to embellish his stories to make them more interesting.”

Today, both of Holand’s Door County histories remain in print thanks to Luchterhand and his Wm. Caxton Ltd editions. Both the Caxton editions have been faithfully reproduced from first editions of each history. In the case of the two-volume history, Luchterhand took apart a first edition belonging to Duncan Thorpe and printed the book via photolithographic offset. Only two changes were made: first the margins were narrowed slightly, though the type size remained exactly as it was originally printed, and second, a photo of cherry blossoms that appeared in the original edition was dropped because it was “fuzzy even in the original,” Luchterhand noted.

Caxton’s edition of Old Peninsula Days was printed in the same manner, though in a paperback edition, and contains all of the original Vida Weborg illustrations.

In the remainder of his long life, Holand went on to write nine more books and became nationally (and, to an extent, internationally) famous for his unwavering belief in the authenticity of the Kensington Stone (see sidebars). He founded the Door County Historical Society and was a driving force in seeing the totem pole that still stands in Peninsula State Park created and erected. In addition, with his participation, the Historical Society purchased lands that are now treasured county parks including Tornado Park, Robert LaSalle Park, Murphy Park, Increase Claflin Park, and The Ridges Sanctuary.

Taken together as a whole, you can see why, during his lifetime, Hjalmar R. Holand was the most interesting man in Door County.

Holand and the Kensington Stone

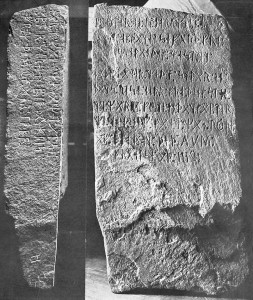

In 1898 Olof Ohman, a Swedish immigrant clearing his land of trees and stumps in the rural township of Solem, Douglas County, Minnesota, claimed he found a stone covered in strange markings in the roots of a poplar tree. The stone is approximately 30” x 16” x 6” and weighs approximately 200 pounds. It became known as the Kensington Stone because Kensington, Minnesota, is the nearest settlement.

Ohman believed the strange markings were Native American and a copy of the inscription (the stone is inscribed on one face with a second inscription along one side) made its way to Olaus J. Breda, a professor of Scandinavian languages and literature at the University of Minnesota, who determined that the writing was Scandinavian runes and concluded the stone was a forgery. Likewise, several of Breda’s associates in Scandinavia also pronounced it a fake.

Holand visited the “small Swedish-Norwegian community … three miles north of the village of Kensington” during his research for History of Norwegian Immigration in 1907. Upon inquiring about anything of historical interest he was told of Ohman’s Kensington Stone.

Holand recognized immediately that the inscriptions on the stone were ancient runes and, after some negotiation, purchased the stone from Ohman and had it transported back to his home in Door County.

Though he became aware of Professor Breda’s dismissive conclusions, Holand compiled his own translation of the runes. Holand’s first translation below appears on the face of the stone while the second translation below appears on the edge of the stone (note that the bracketed words do not appear in the inscription):

[We are] 8 Goths and 22 Norwegians on [an] exploration journey from Vinland through the West We had camp by [a lake with] 2 skerries one day’s journey north from this stone. We were [out] and fished one day. After we came home [we] found 10 men red with blood and dead A V [e] M [aria] Save [us] from evil.

[We] have 10 men by the sea to look after our ships 14 days’ journey from this island [in the] year [of our Lord] 1362

Holand managed to have the stone’s authenticity endorsed by the Minnesota Historical Society, chiefly through the recommendation of Professor N. H. Winchell, but the debate raged on. For each supporter there were two who claimed it a hoax. As Holand noted in My First Eighty Years: “Thus it happened that I became involved in a scholastic inquiry which has lasted half-a-century and the end is not yet. It has been my chief subject of study and meditation, about which I have written four books and more than a hundred articles in various periodicals. It necessitated three research trips to European universities and museums and each year I have made at least one trip to northwestern Minnesota to investigate new finds and circumstances.”

This ongoing research led Holand to search for mooring stones. In essence, a mooring stone is “a big boulder on the shore of a lake or big river, which serves as a pier, to which a large or heavily laden boat can be moored. To make this effective a hole is drilled into the top surface of the boulder. This hole, from six to eight inches deep, is for the insertion of a ringbolt to which the painter of the boat is tied.”

Holand claimed to have found 10 such mooring stones in Minnesota and offered them as evidence of Scandinavian exploration in the Midwest.

Today the Kensington Stone is housed in the Runestone Museum in Kensington, Minnesota, and though the preponderance of opinion still holds the stone to be a forgery, ardent supporters still insist on its authenticity.

Hjalmar Holand Bibliography (listed with original publication dates)

History of Norwegian Immigration, 1908

History of Door County Wisconsin: The County Beautiful, 1917

Old Peninsula Days, 1925

Coon Prairie, 1927

Coon Valley, 1928

The Last Migration, 1930

Wisconsin’s Belgian Community, 1931

The Kensington Stone, 1932

Westward From Vineland, 1940

America 1355 – 1364, 1946

Explorations in America Before Columbus, 1956

My First Eighty Years, 1957

A Pre-Columbian Crusade to America, 1962

NOTE: Virtually all of Holand’s books are now in the public domain and free from copyright restrictions. Thus, if you go to search books from Holand today you will find numerous other titles reissued by various publishers. Any title that does not appear in the list above is typically a portion of one or another of the above titles republished with a new title, or is in fact one of the books listed above published under another title.