Door to Nature: Royal Fall Wildflowers

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

The exciting array of showy wildflowers that decorates northeast Wisconsin’s country landscape in all directions might be called the “royal purple and gold” of autumn.

One of my absolute favorites is the New England aster, which is in peak bloom by late September. Asters — sturdier and more successful than most wildflowers — are in the composite family, the largest in the United States. This amazing plant family has representatives in the great majority of yards, gardens and fields. Ornamental flowers include zinnias, dahlias, chrysanthemums, asters and sunflowers.

The scientific name for the genus has been replaced by new labels, but nevertheless, we can still call them asters. These conspicuous, widespread plants are largely perennials that range in color from white to blue, lavender, pink, purple and a host of intermediate shades.

An aster blossom is made up of thin, outer, strap-shaped ray flowers and a closely packed cluster of disk flowers, so that what is referred to as one flower is actually many individual flowers. Pick an aster blossom, carefully pull it apart down the center, and you can easily examine the individual parts. A magnifying lens will help considerably.

Each ray flower consists of what is normally called a petal. Attached to the inner end, angled upward, is a small, Y-shaped stigma. Fastened to the inner end of the ray flower, which is a pistillate flower, but angled downward, is the ovary, which, when fertilized, will produce a fruit. This is often erroneously referred to as a seed.

Fastened to the upper tip of the ovary is the pappus, a cluster of tiny hairs or bristles that takes the place of the calyx, or group of sepals, in individual flowers and eventually serves as a parachute to carry the ripened fruit to a new location.

The central part of the blossom — the cluster of staminate disk flowers — is usually yellow at first, but it turns to red as the flower ages. Each tubular disk flower contains a thin, Y-shaped stamen. Long-tongued insects such as bumblebees and butterflies can reach the nectar in the tubes, and some animals, including ruffed grouse, tree sparrows, cottontails and even white-tailed deer, occasionally make use of the “seed” heads as food.

Several easily seen characteristics will help you learn about some of the asters. Your knowledge of plants in general will improve as you study features such as the leaf size and shape, the margins of leaves, whether the leaves clasp the stem, the size of flower heads and the color of ray flowers and the stem.

Asters are primarily North American flowers, with around 150 species found here. They grow sparingly elsewhere around the world. Canada has 60-70 species, and Europe and Russia each host 10. What’s exciting about asters is that they live in so many different habitats, from wetlands to prairies, deciduous to evergreen woodlands, and environments that are practically deserts to cold, wet bogs.

The other widespread autumn wildflower that graces many fields and roadsides is goldenrod. Wisconsin is home to about 28 species and varieties — a rather large percentage of the approximately 100 species found in the United States.

The genus name for goldenrod is Solidago (sol-i-DAY-go), from the Latin “solidare,” meaning “to join or make whole.” In olden days, it was common to cut goldenrod plants into small pieces, boil them in water and use the cooled liquid as a healing wash for wounds.

A favorite that used to grow in our front yard is Canada goldenrod. Some plants grew to a height of six feet and had large flowers. Another that’s easy to identify — because of the tendency of the flower tip to bend over — is gray goldenrod, or dyer’s-weed. Due to poor soil in the ditches where many of these plants grow, they are frequently no taller than 10 inches. They’re small, dainty plants with fine hairs on the stems that give them a grayish cast.

One of the earliest to bloom, often in August, is the flat-topped Ohio goldenrod, which can be found near the shore of Lake Michigan. One of the rarest species — dune goldenrod — is also seen along sandy beaches in a few areas. It can be identified by its narrow, plume-like inflorescence and deep-maroon-colored stem.

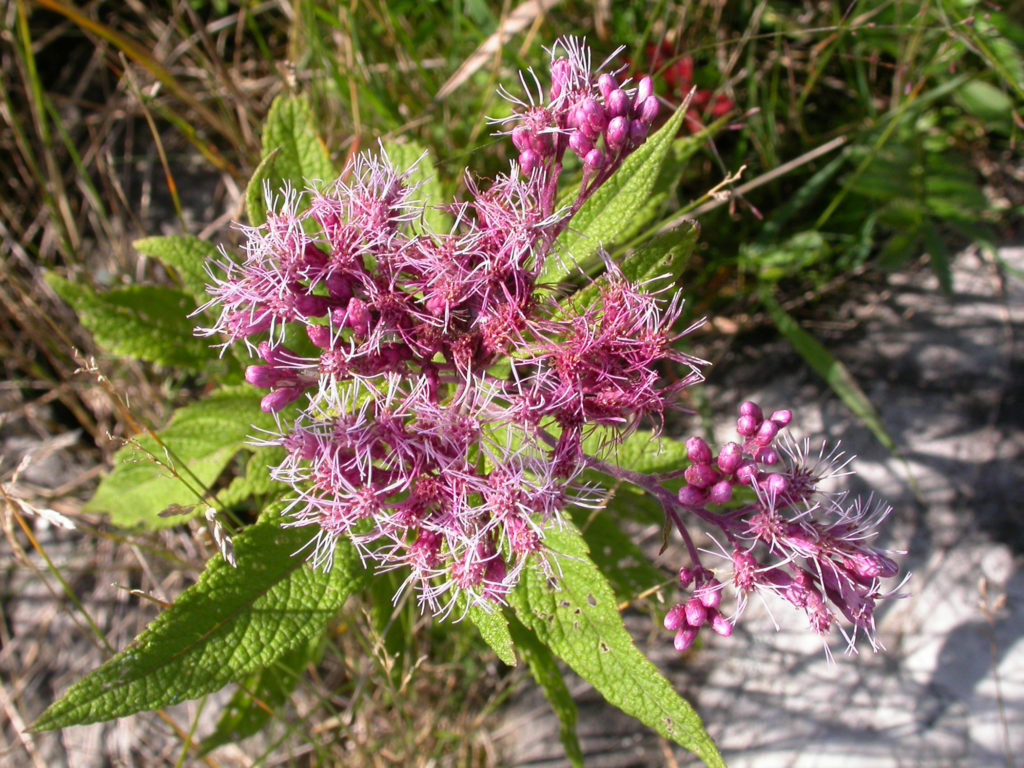

The tall bog goldenrod is a real beauty that often grows by itself in sunny wetlands. You may also find another tall, purple flower growing in the same wetland, continuing the purple-and-gold theme of autumn. That plant is joe-pye weed, in the genus Eupatorium (you-pa-TOR-ee-um) and also a member of the composite family.

The soft, wine-colored sprays of joe-pye weed that are sometimes seen in roadside wetlands will be on plants that may reach a height of eight feet. You don’t realize how numerous and widespread these native wildflowers are until they come into bloom.

The last of the golden flowers of fall are sunflowers. Little did the Greeks realize that two of their words — “helios” (HE-lee-ohs), meaning “the sun,” and “anthos” (AN-thos), meaning “a flower” — would be combined to form a word describing one of the warmest, most radiant, sunshiny plants known to humankind: Helianthus (he-lee-AN-thus), or the sunflower.

Native Americans knew this plant well and used its seeds for food, flour and cooking oil; its stalks for fuel; and its ashes as fertilizer. What the Native Americans may not have realized technically, but knew through many years of use, is that sunflower seeds are extremely nutritious: They’re rich in protein, calcium, phosphorus, thiamin, riboflavin and niacin.

Sunflowers — wild, as well as those grown in gardens — also belong to the composite family. It is the disk flowers that develop into the wonderful seeds that humans and many bird species relish.

Get out to enjoy the landscape’s purples and golds during the “royal” days of autumn. Take time to slow down, observe carefully and be grateful for the last “rays” of summer as we enter the fall season.