Door to Nature: Snow, Ice and Jack Frost

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Photography by Roy Lukes

One of the great joys of living in the North Country is watching a “mega-flake” snowfall. It was in mid-February 1985 when such an event began. The flakes were huge, flat and fell with very little wind, making them drift down like chicken feathers, as our good friend Ted Kubicz described them. I turned on the powerful yard light occasionally to watch them fall in the darkness of the storm.

That snow continued for 48 hours and amounted to 30 inches on the level. It was concentrated in a wide band from Egg Harbor to Baileys Harbor. It even made the national news, with Willard Scott highlighting the event on the morning Today Show.

Once the snowfall ended, I began shoveling off the deck, and Roy got on his old Ford Ferguson tractor and began plowing the driveway. I watched as he slowly headed south, and all the snow that was pushed aside immediately fell back onto the driveway behind him. We had to call a neighbor on a farm close by who came over on his tractor — fitted with a six-foot-wide snowblower — and successfully cleared our driveway.

There are many definitions of snow. The Encyclopedia Britannica says snow is “the solid form of water which grows while floating, rising or falling in the free air of the atmosphere.”

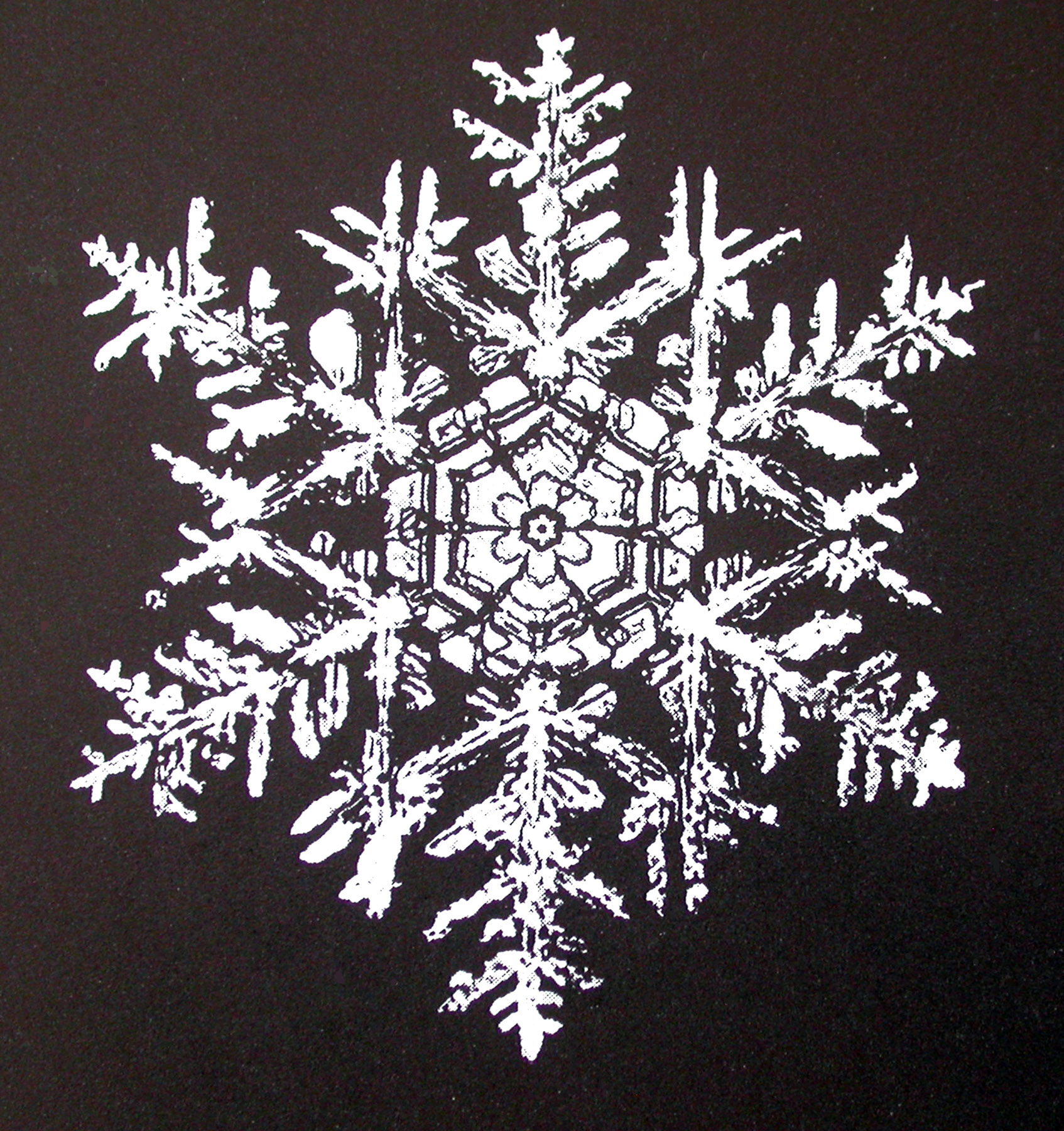

The word “crystal” comes from the Greek word “kryos,” meaning “frost.” Snow crystals, dainty and brittle, are generally hexagonal in pattern and are grouped by snow experts into types such as plates, stellars, columns, needles, spatial dendrites, capped columns and irregular crystals. They form in a wide range of shapes, from simple triangles and hexagons to lacy, fern-like dendrites.

Snow crystals grow rapidly whenever there is a rich supply of moisture in the air. It is common for a single snowflake to have 50 or more interlocking crystals. Given that, each of the “chicken feathers” that we saw fall in February 1985 surely must have been made up of dozens and dozens of individual snow crystals joined together.

Even the wispy cirrus clouds five to eight miles high that are seen during the summer in the middle to low altitudes are composed of ice crystals. Cirrus clouds commonly occur at low elevations in the polar regions. Remember, too, that much of the moderate to heavy rain in our region begins as snow.

When we lived in the upper Ridges Rangelight, Roy kept the snowplow tractor in the garage — so that it would always start when needed — and thus he had to leave our van outside. One cold morning, he discovered that Jack Frost had visited overnight and had painted wonderful filigree patterns on the windshield.

Every section of this snowflake has equally beautiful features.

One January day when I worked in Sister Bay and had an early-morning drive, I saw gorgeous hoarfrost on everything in the countryside about four miles north of Baileys Harbor. There was a clear sky; the air temperature was five below; and the air was calm. I called Roy when I got to my office and told him to try to photograph the beautiful, icy sheets lining many branches and shrubs. It took him several minutes of shooting pictures before he realized that his camera lens was beginning to freeze.

This extraordinary form of frost usually occurs in midwinter at low temperatures. Weeds, barbed-wire fences, shrubs, trees — everything was trimmed with fragile, jagged, nickel-to-quarter-sized, flat, pointed discs of frost of incredible beauty. Roy remembered that as the sun rose and a gentle breeze developed, the tinkling “music” of the huge crystals as they disintegrated and fell to the ground produced another sensation never to be forgotten.

It was about 130 years ago that a bachelor farmer named Wilson Alwyn Bentley of Jericho, Vermont, perfected the technique of photographing a single snowflake through a microscope. His efforts revealed to the world the intricate grandeur and mystery of the snowflake, its universal hexagonal shape and its infinite number of lovely designs.

Snowflake Bentley, as his friends called him, shared freely with others — especially young people — the splendor of snow crystals as seen in his photographs and writing.

Snow crystals are of extraordinary beauty, perfectly shaped because they are free-formed from water vapor in the upper atmosphere. Air, cooling after the sun goes down, can’t hold as much moisture as it can during the day. The summer version is dew: it forms on cool objects, including plants, spider webs and flower pots.

In winter, this vapor turns to frost when the air temperature is below 32 degrees F. It does so by an interesting process called sublimation. That is, it’s transformed from an invisible gas (vapor) directly into a solid: the lovely, delicate, six-sided symmetry that you may have to scrape off your car’s windshield on one of these winter mornings in Door County.

In regard to snowflakes, the more solid, six-sided crystals form in the intense cold of the higher atmosphere, and the delicate, feathery snowflakes — the ones most people know — develop in the lower clouds where the air is still, moisture abounds and the temperature is only slightly below the freezing point. The air temperature drops, on average, one degree F for every 300 feet of elevation above the ground.

You can observe snowflakes at their best shortly after a snowfall begins because later during the storm, crystals collide, resulting in large, rather shapeless masses of snow. Wear dark clothing; use a 10-power magnifying hand lens; and hold your breath as you closely examine the elegance of the shapes of those six-sided masterpieces.

Snowflakes are white due to the many extremely small reflecting surfaces that form along with the air spaces that are trapped between these surfaces. Surely one of the great marvels of nature is how the awesome and powerful forces of a blizzard can come from such fragile, exquisite, dainty, white snowflakes. Bentley called them “gems from cloud land” and said, “There are snowflake jewels for every conceivable occasion.”

What’s amazing is the fact that one stellar snowflake can be so light and delicate, yet multiplied by millions, it produces enough weight to push an evergreen tree to the ground! Play it safe by respecting the phenomenal splendor — and power — of a Door County winter. But don’t let the mile after mile of ice, and drift upon drift of snow, hide from view the delicate beauty of a single snow crystal.