Drawing Lines: Door County’s Geographic Rivalries

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Can defining what divides us help bring communities together?

It simmers just beneath the surface of many a Door County conversation – a rattling lid barely keeping it from boiling over across a bar, into the ink of a letter to the editor, or onto the diamond from along the fence at a county league ballpark.

“It” is that strong sense of competitiveness among the communities of Door County and the perceptions, both founded and not, that we all have of our neighboring communities. It’s something you sense intuitively if you’re from here, something you acquire if you stick around long enough, and something newcomers struggle to grasp.

Aside from Sturgeon Bay, all of Door County’s towns and villages might appear fairly similar to the eye of the un-initiated. Sure, they have their little style quirks (like Ephraim’s obsession with white paint and Egg Harbor’s blue sidewalk lights) but they’re all small towns, they’re all pretty sleepy in the winter months, and they all have a similar mix of core businesses – a gas station, a food mart or grocery, a hub intersection where traffic “jams.” But to the people who live in each of these towns, especially those who grew up in them, community blood runs thick through their veins.

Bobby Schultz is a Haba Boy through and through, and a dedicated caretaker of the A’s admired field. Photo by Len Villano.

If you want proof, try your luck telling somebody who grew up in Baileys Harbor that his town is pretty much the same as Fish Creek or suggest that Egg Harbor is better than Ellison Bay. Or, if you want to risk getting kicked out the front door, try asking a Sturgeon Bay shopkeeper how much farther north you have to drive to get to Door County.

“You wouldn’t believe how often people ask me that,” a retailer on Sturgeon Bay’s west side once told me. “It makes me so mad. We are in Door County! And I really hate it when they say, ‘Well, you know what I mean. Like, really in Door County.’” She shook her head and huffed a big, calming exhale. This was coming from a shop owner who could walk to the end of her driveway, look down the highway, and see the bright sign of the Door County Visitor Bureau Welcome Center.

There are more than a few residents who won’t set foot in certain other towns unless it’s absolutely necessary, and the community ribbing is often merciless.

“The best thing that ever came out of Baileys Harbor,” John Bastian once said, “is Highway 57.” Bastian is famous for stoking the fires of “Grudge,” the Door County League Baseball rivalry between the Sister Bay Bays and Baileys Harbor A’s. Ironically, Bastian actually starred as a pitcher for both sides in that notorious rivalry, winning a league championship with “the Haba,” but even a title didn’t soften those old town lines.

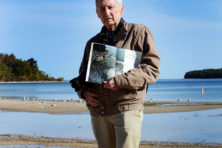

Bobby Schultz sits on the other side of that rivalry, one of Baileys Harbor’s proudest and a member of the town board. Quick to laugh and generous with his smile, Schultz has friends all over the peninsula, no doubt a byproduct of years playing Door County League Baseball and working for the Door County Highway Department. When I spoke to him a few years ago about the football and soccer facility project he had just spearheaded in Baileys Harbor, he was careful not to say it was better than any other town’s park.

WDOR’s Eddie Allen calls a Door County League Baseball game, a signature aspect of many a Door County rivalry. Photo by Dan Eggert.

“We’re proud of it,” he said, his beaming face making that plain to see. “But we don’t want to take anything away from what Sister Bay has built up there. They got a nice thing going on. They have the ice rink and broomball, and we have football and soccer.”

Schultz was being diplomatic, but as someone who grew up in Baileys Harbor when the town kids still attended elementary school at the Baileys Harbor School (now Orphan Annie’s) he knows there are still certain perceptions people have about their neighboring communities.

“I like Sister Bay, but when I was growing up, it just always seemed like the Sister Bay guys thought they were better than everyone else,” he says. “They thought they were the big city and we were all hicks.”

A woman I spoke to who grew up in the Appleport area a few miles east of Sister Bay proper couldn’t deny that there was a little truth in Schultz’s impression.

“Well, we did think we were better,” she said with a laugh. “But it wasn’t just Baileys Harbor. If you were from Appleport, you couldn’t go to the Sister Bay beach. That was only for the kids who went to the old Sister Bay school. We had to go to Sand Bay [beach]. We didn’t even consider Egg Harbor part of Door County back then.”

That, of course, may be the biggest point of contention – which part of the peninsula is the “true” Door County. A lot of folks in official positions will tell you it’s a stupid argument – “I don’t buy into that crap anymore,” Schultz says, “we’re all in this together” – but the debate continues amongst the rest of us anyway. When folks really want to start an argument, they’ll begin moving the county line, with Sturgeon Bay folks cutting off Southern Door, and Northern Door folks cutting off Sturgeon Bay.

Those in the north like to define Door County by its tourism brand, a relatively new phenomenon that took hold after the industry boomed when National Geographic magazine ran a feature article about the peninsula in 1969. For decades the bulk of visitors flocked to Ephraim, Fish Creek, Sister Bay, and more recently Egg Harbor; the rest of the county largely eschewing the tourists pocketbooks.

It’s not uncommon for Northern Door workers to say that the real Door County starts a few miles north of the Bayview Bridge, and not totally in jest.

Farming remains integral to the life of Southern Door residents, but has slowly disappeared in Northern Door. Photo by Dan Eggert.

But if any community can lay claim to the most authentic connection to the county’s historical roots it may be Southern Door, where agriculture still dominates the landscape in Brussels, Gardner, Forestville, and their surrounding towns. According to George Evenson, president of the Door County Historical Society, at least 50 percent of farmland in the area in and around Brussels in Southern Door is still farmed by descendants of the original Belgian settlers that claimed plots there in the mid-1800s.

Only a quarter century ago farms and orchards dominated the Northern Door landscape as well, but as property values skyrocketed and development of condos, shops, and vacation homes boomed, the farming heritage of the northern end of the peninsula faded.

North vs. South

Sturgeon Bay, meanwhile, is an island of its own, split by a canal that once created a fierce East Side/West Side rivalry. Today it’s a city in transition, warming to tourism, but still justly proud of its industrial heritage as a working waterfront.

Shipbuilding defines Sturgeon Bay, and for decades, the industry employed hundreds of Northern Door farmers in the winter months. Photo by Dan Eggert.

The city is home to county government, the county’s major hospital, the Department of Motor Vehicles and the Door County Courthouse. Nearly 60 percent of the county’s residents work in the city, though it is home to just a third of the county population. These factors create a powerful dynamic that may be at the root of the feeling many in the city have that, when it comes to county politics, it’s them versus everybody else – everyone living outside the city needs to go there, while those who live in the city don’t need to go to the other communities for anything.

“I know someone on the county board who has never even been to Cana Island in Baileys Harbor – a county park,” says Dan Austad, a Sturgeon Bay resident who has served on the Door County Board of Supervisors for 28 years.

Eddy Allen has been broadcasting the county’s news and sports over the airwaves at 93.9 WDOR radio for more than 40 years. He says he runs across people fairly often who’ve never been to Sister Bay or Baileys Harbor. “It’s not on the way to anywhere,” he says.

Though the stark dividing lines of the past are harder to identify, Evenson – who has spent all of his 82 years on the same property in Sevastopol – says the accepted borders of Northern Door remain largely unchanged.

“You could argue that Northern Door starts when you get over the bridge,” he says, “but as a long-time resident, I always thought it was pretty much a line from Egg Harbor to Jacksonport and north.”

Urban vs. Rural

Northern Door is an area reliant almost exclusively on the tourism economy and features an interesting internal dynamic of its own. It has a large population of wealthy second and seasonal homeowners and retirees dependent on services provided by a local population of servers, shopkeepers, and tradesmen.

That breeds an unorthodox urban versus rural dynamic in a county where it’s a stretch to use urban as an adjective. (My father, himself a Chicago transplant, calls it “a peninsula of rural communities and urbanized influences.”) City transplants and seasonal residents from Milwaukee, Chicago and St. Louis heavily influence the population of Northern Door, creating a culture and vision often at odds with their Southern Door counterparts

For many who grow up just 15 or 20 minutes south of Evenson’s Egg Harbor demarcation, their first trips to Northern Door come when high school sports teams from Southern Door or Sturgeon Bay travel to Fish Creek for a game. As a result they might only see

Fish Creek or Egg Harbor in the offseason, when the streets look all but abandoned.

To many Southern Door residents, Northern Door is a land of artists and wealthy second home owners only. Photo by Dan Eggert.

With a large contingent of second homeowners, Northern Door appears to many from the south as a land of wealth. As a friend who grew up in Sturgeon Bay and later waitressed in Sister Bay told me, “I think everyone kind of saw up north as being all tourists and rich kids. They don’t realize that there’s this huge working class population in Northern Door that works in the restaurants and hotels.”

Or, as Allen says, “You see all those fancy houses along the water when you go up there, and you assume that’s how everyone lives.”

Part of that perception can be traced to a glance at a restaurant menu. In Southern Door you can still get a fish fry for under $8 if you know where to look, and a lunch for less than $5, so when those residents travel north they experience a dose of sticker shock. “I know guys who absolutely hate Northern Door,” Schultz says. “They say they can’t afford to come up here.”

Wherever they’re from, Allen says folks on both sides of the argument trumpet the same complaints. “People in Southern Door feel like they get treated worse than the city and Northern Door when it comes to county services,” Allen says. “They’ll tell you all the good things go north because they get all the tourists. And folks in Northern Door think everything goes south because that’s where the city is. And of course everybody thinks the other part of the county gets their snow plowed first.”

That waitress friend recalled that her co-workers in Sister Bay nicknamed her SBT – Sturgeon Bay Trash. It was a joke, the kind of friendly ribbing common in the restaurant world. “I guess it implies that all we do in Sturgeon Bay is hang out at Wal-Mart and go to the races. When my shift was over we would joke about going home to the ghetto, because that was kind of the perception.”

The ribbing trickled down though, each town finding their own counterpart to knock.

“In Sturgeon Bay, we would take it out on Brussels,” she said. “Like Southern Door is a bunch of hicks or less educated. It’s all in good fun though. We always called Southern Door cow-pie high, but the reality is it might be the best school up here.”

Coming Together

In younger generations the battle lines have softened. The consolidation of one-room schoolhouses between 1960 and 1990 went a long way toward easing some of the old town rivalries. Then came the increasing complexity of local government, driven in large part by the challenge of creating a suburban level of service for a three-month population boom in otherwise rural communities.

That complexity made it harder for municipalities to operate as islands. In the 1990s municipalities had to start talking to each other and working together to survive. Fire departments merged services, relying on each other for mutual aid and training, and joint libraries were created. Then as the century turned it became apparent that traditional industry was dying and tourism was the best bet to fill the void. In 2007, a coalition of tourism advocates finally convinced all 19 municipalities to sign on as members of the Door County Tourism Zone Commission and collect a uniform room tax, an achievement deemed unthinkable just 10 years earlier.

In the end, the community pride that often divides us isn’t all that uncommon, Austad argues. Most cities, he says, have a north side and south side, or an east and west. Most counties have an urban center and rural outposts. “I don’t think it’s unique to Door County,” Austad says.

Though it may not be unique, understanding what those different perceptions are and where they come from helps you understand how decisions are made, how rifts develop, and most importantly, how to overcome them.