A Failed Social Experiment: Prohibition in Door County

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

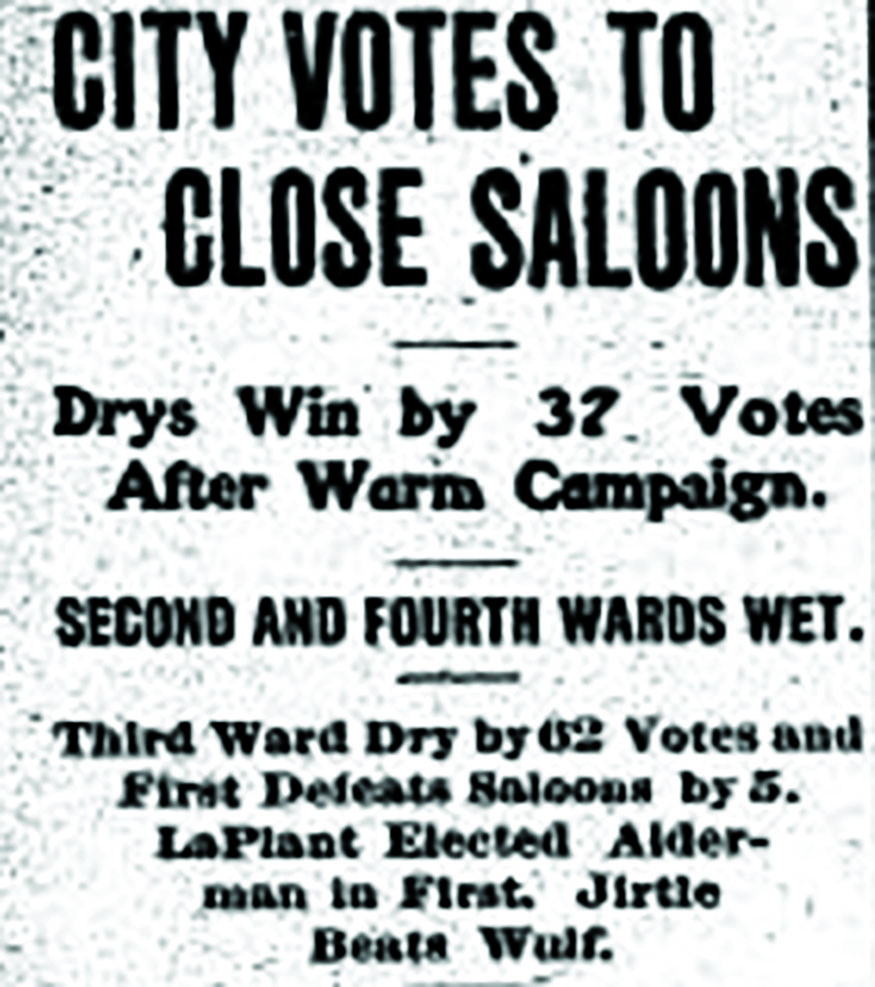

Eleven long and rocky years before America went dry by Constitutional Amendment, most of Door County voted to shut down its saloons.

In the April 1909 election, all but two of the county’s municipalities voted to go dry. Baileys Harbor and Nasewaupee were the wet holdouts.

In the city of Sturgeon Bay, the vote was 526 to 489, or 37 votes in the majority for dryness, as reported prominently on the front page of the April 10, 1909 Door County Democrat:

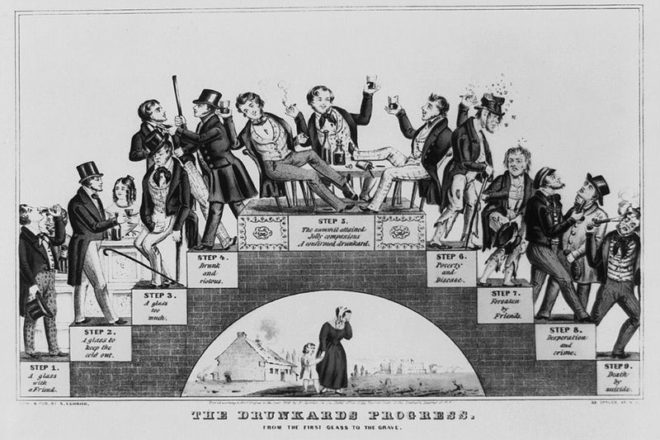

It was no big surprise. The dry movement had been a long-simmering political force that found its most strident voices in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which was founded in 1874, and the Anti-Saloon League, founded in 1893.

From the late 19th century well into the 20th century, Door County newspapers printed a WCTU column. A Sturgeon Bay branch of the WCTU was in existence into the 1960s.

The political arm of the anti-drink movement is known as the Prohibition Party, the oldest third party in existence. The Prohibition Party’s 2012 presidential candidate Jack Fellure, a perennial presidential candidate since 1988, took home an impressive 518 votes, because who even knew the Prohibition Party still — or ever — existed?

And in case you hadn’t heard, the Prohibition Party has candidates in the 2016 presidential election. They are 20-year Marine Band veteran Jim Hedges and former high school band director Bill Bayes (hedgesandbayes2016.org).

Pledge of the Wisconsin Temperance Society

We, the undersigned, do agree, that we will not use intoxicating liquors as a beverage, nor traffic in them — that we will not provide them as an article of entertainment, or for persons in our employment — and that, in all suitable ways we will discountenance their use throughout the community.

Wisconsin Temperance Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1, Milwaukee, April 1840

The first temperance society in the Wisconsin territory was formed in Green Bay in 1835, led by Thomas and Nelson Olin, New Yorkers who had moved to Green Bay two weeks before the society formed, according to the Green Bay Press Gazette of May 25, 1921.

In 1839 the territorial legislature was asked by Samuel and Henry Phoenix to create a dry county named Walworth, after a prominent eastern temperance leader. By the 1850s, the experiment was abandoned. The Phoenixes began a temperance colony in Delavan, where a Temperance House was built in 1840 that still stands. The first annual meeting of the Wisconsin Temperance Society was held February 13, 1840, in Troy, Wisconsin.

The confluence of the dry movement and World War I made conditions ripe for enacting national Prohibition. In August 1917 the Lever Act was approved. It banned distilled spirits production for the remainder of the war in favor of grain for food production. Anti-German sentiment was strong, and most of the breweries of the day were German owned, so it was easy to support the war effort by being dry. By 1919, 27 of the 48 states had enacted prohibition laws (including Wisconsin).

You can see in those old WCTU columns that the group was at first not naïve enough to believe it could make all of America dry, but it did hope to curb the influence of the saloon on domestic life. Once Prohibition was in effect, WCTU members recognized they were surrounded by scofflaws.

“You laugh at the Prohibition laws; the libertine laughs at the marriage laws; the anarchist at the property laws — watch out that your son does not laugh at all laws. Let’s quit laughing at any law!”

— from a WCTU column in the Dec. 20, 1923 Door County News

The decision to advocate for Prohibition appears to be a fundamental failure in understanding human nature by leaders at all levels, for there is one absolute certainty in this life: Prohibit something and an underground movement of avid anti-prohibitionists will spring up somewhere. That is both part of human nature and the American way. Or as Will Rogers once put it, “Why don’t they pass a constitutional amendment prohibiting anybody from learning anything? If it works as well as prohibition did, in five years Americans would be the smartest race of people on Earth.”

The hatchet-wielding Carrie Nation claimed she had divine ordination to promote temperance by destroying saloons. She was arrested more than 30 times for her “hachetations.” She is seen here in a 1910 public domain photo.

Among the many unintended consequences of Prohibition was the creation of a new class of criminal, not to mention $11 billion in tax revenue the federal government lost during that 13-year period of legislated abstinence.

With so many people against Prohibition at all levels of society, there were, of course, many loopholes in the law. Doctors could prescribe alcohol, and pharmacists could dispense alcohol. The number of “pharmacists” in New York State tripled during Prohibition. People of the Jewish faith could drink upon the advice of their rabbi. Suddenly everyone had a rabbinical dispensation. Catholics still needed their sacramental wine. Orders for red wine from Catholic churches tripled. Homebrewing of beer and wine probably rivaled today’s homebrew movement, in numbers if not technique.

Danish immigrant Tom Nelson skirted Prohibition at his bar on Washington Island by obtaining a pharmacist’s license and dispensing 90 proof Angostura bitters “to calm upset stomachs.” Today, Nelson’s Bitter Hall continues to serve shots of bitters to guests who want to join the Bitters Club, which gives the place two distinct claims to fame — the longest continuously operating bar in Wisconsin and the biggest consumer of Angostura bitters.

The Hotel Roxana, at the corner of 3rd and Kentucky in Sturgeon Bay, kept the wets happy during Prohibition.

Prohibition also exhibited a great divide in America. The federal government in its justification for its failure in enforcement blamed a “foreign element” for the continued failure to contain America’s thirst. True Americans, the feds reasoned, would abide by Prohibition, but Germans and other European immigrants obviously were not fully assimilated because they were unwilling to give up their beer and wine for this great experiment in Americanism.

On the other end of the spectrum, the then-thriving Ku Klux Klan was both anti-immigrant and virulently pro-Prohibition. At their height in the mid-1920s they claimed 15 percent of the “eligible” population in the United States belonged to the organization, or as many as four million adherents. The Klan during Prohibition years was known as the extreme militant wing of the dry movement.

The large “foreign element” in Door County — almost 9,000 of its 19,000 residents in 1929 were identified by the feds as “foreign element” — led to it being identified as “very wet” in a 1929 federal survey of enforcement efforts in Wisconsin, one of only five counties in the state (along with Iron, Marathon, Sheboygan and Taylor counties) to be so recognized (as opposed to just wet or dry).

“Wisconsin, to the average American unacquainted with actual conditions therein, is commonly regarded as a Gibraltar of the wets — sort of a Utopia where everybody drinks their fill and John Barleycorn still holds forth in splendor. From the standpoint of actual votes and of present conditions, Wisconsin is undoubtedly a wet Commonwealth.”

— Federal agent Frank Buckley, beginning his 1929 report on Prohibition enforcement in Wisconsin

During Prohibition, soft drink parlors popped up everywhere. Today we know them as speakeasies, but Door County newspapers of the Prohibition era never mention the bust of a “speakeasy” but the bust of “soft drink parlors” was a common event.

OFFICERS MAKE RAIDS

SATURDAY EVENING

Under the direction of Mayor Green the police on Saturday evening made a raid on the soft drink parlors of Jule Mallien and Albert Lautenbach in the fourth Ward and secured a quantity of moonshine…

Door County News, February 5, 1925

GETS JAIL AND FINE

George Paul, proprietor of a soft drink parlor and dance hall in Sevastopol, charged for the second offense with possessing illicit liquor, was fined $200 with about $14 costs and sentenced to serve 30 days in the county jail.

Door County Advocate, September 14, 1926

The beginning of Prohibition was marked by the Door County Advocate with a front page editorial on January 16, 1920, the day Prohibition began. The newspaper pointed out that Sunday, January 18, was designated “Law and Order Sunday” and clergymen throughout the land were asked to bring attention to the importance of obeying laws as the cornerstone of Americanism. The editorial also pointed out that when a preacher in Appleton complained to police that a local saloonkeeper stayed open on Sunday and even sold liquor, the case went to trial and the jury acquitted the saloonkeeper but fined the preacher $5 for working on Sunday. The editorial ended with this thought: “They say to make the law effective the sentiment of the people must be for it.”

The law was in effect for 13 years, but it was never an effective law for that very reason — only some of the people were for it.

Searching through old newspaper files, you see some names recurring in connection with Prohibition. One of those is John Peltier, a Door County commercial fisherman and farmer who was elected to the state Assembly. In an April 1923 interview with a Milwaukee newspaper, Peltier also revealed that he was a Spiritualist who received legislative guidance from voters beyond the grave. The report went on to say that Assemblyman Peltier “has received frequent pro-dry inspirations from the other world with a result that he is convinced that the wet movement can bring nothing but evil if it is successful.”

A full-page ad (which cost $42, it states on small print at the bottom) in the October 28, 1926 Door County News by the Wisconsin Division Association Against the Prohibition Amendment asked folks to “vote YES on the Beer Referendum” and “A Vote for BEER is a Vote for Farm Relief!”

The Paul family of Door County had no qualms about where their sympathies were during Prohibition. Photo courtesy of the Door County Historical Museum.

The ad went on to explain that prohibition reduced the demand for barley, not just for brewing beer, but for making bread for the sandwich that you would have with the glass of beer. The ad lists the many sacrifices farmers had to make because of the Volstead Act, including $90,250,000 lost revenue annually in brewers’ grains.

The same organization produced an ad in 1929 that took another tack against Prohibition: “Our Wisconsin police, if kept busy chasing bootleggers and raiding speakeasies, have no time to spend on murderers and burglars.”

Wisconsin’s Republican Governor John Blaine began to openly question the wisdom of Prohibition as early as 1923. Blaine is largely forgotten today, but he was known in his time as the “Father of the 21st Amendment” for having led the repeal movement as a United States senator when he introduced the 21st Amendment to repeal the Volstead Act on December 6, 1932. So you might want to tip a glass to Senator Blaine.