Farming the Peninsula: Inflation of Agricultural Education

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

The days of riding in the tractor with dad and taking over the family farm soon afterward are over. As an increasingly complicated job, farm operators have seen an increase in the level of education they need to successfully run a farm.

“It used to be uncommon,” said Southern Door farmer Eric Olson about formal education in agriculture. “You used to just get done with high school and come back to the farm.”

Olson is one of the many farmers in his generation who attended the Farm & Industry Short Course (FISC) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. It is a one- or two-year crash course on the farm industry.

But Olson’s son, Zach, plans on going to college for his four-year dairy science degree at Madison or River Falls. A sophomore at Southern Door High School who is involved with the local Future Farmers of America (FFA) chapter, he admits the decision has a lot to do with simply wanting the college experience, but he is not alone in seeking a high level of education.

“You went from no college to short course to now everyone is getting four-year degrees,” said Austin Vandertie, senior at Southern Door High School who also plans on getting his four-year dairy science degree.

“Initially I was looking just at short course [FISC],” Vandertie said. “When I looked at the four-year program, you get a lot more interaction with people who are going to be in the industry of agriculture, not just on the farm. You make those connections that last with you for a lifetime.”

Don Niles, owner of Dairy Dreams, said those connections are essential in modern agriculture.

Economics professor William H. Kiekhofer, shown here in the late 1940s, lectures in the large Agricultural Hall auditorium. Agricultural Hall was completed in 1903. Photo courtesy or UW-Madison Archives.

“The world has gotten way too complex for any one person to be a master of everything,” Niles said. “But now we have access to people that know everything.”

The explosion of ancillary businesses to farm operations is one of the biggest changes in agriculture in the past few decades.

Melissa Bender, director of education and programming for the new Farm Wisconsin Discovery Center outside of Manitowoc, said agriculture education has expanded and become more specialized.

“They focus more on getting back to hands-on but catering to students so that it’s not just dairy,” Bender, a former agriculture educator, said. “There’s so many other opportunities in the agriculture industry.”

“It’s part of the increasing complexity of the job,” said Dr. Kent Weigel, chair of the Department of Dairy Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “Technical parts, nutrition, genetics reproduction, the ability to integrate all those pieces of information, it’s crazy what you have to be able to do.”

Weigel agreed that higher education is becoming a more essential part of farming, primarily due to the increasing use of data.

“You don’t walk on a farm and sniff the feed,” Weigel said about the changing dairy science curriculum. “Dairy management starts by downloading all the data from the farm and doing diagnostics before you ever step foot on it. You want to look at it objectively first.”

Weigel said the objective data-driven side of the new agriculture curriculum also helps farms tailor their practices because not all farms are alike. While best management practices have their place in proper farm management, farms within one mile of each other can have dramatically different characteristics. Analysis of geography, nutrient management and soil health through data can tailor practices more effectively, but those analytic skills are hard to learn by simply working on the farm.

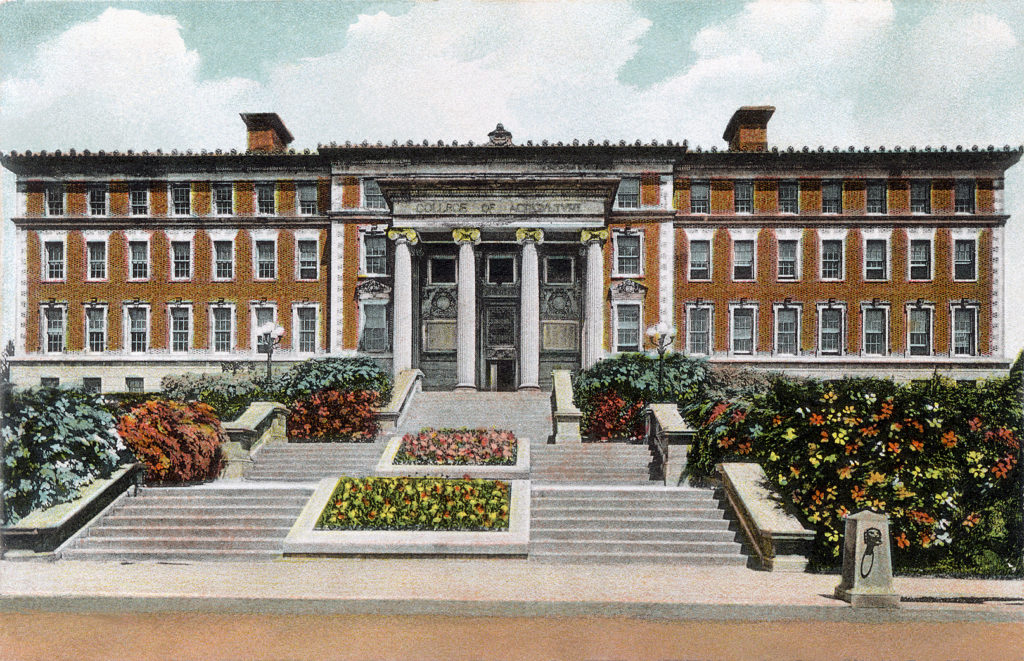

Historical photograph of the classic Beaux Arts-style Agricultural Hall completed in 1903, from a colorized postcard probably dating from the 1920s or 19030s. Photo courtesy of UW-Madison Archives.

“It takes a lot of moving parts to keep a dairy farm going because you got to milk and you have to more intensely care for the animals so you need people to fix those things,” said Tony Brey, co-owner of Cycle Farm Holsteins in Sturgeon Bay.

Lee Kinnard, owner of Kinnard Farms in Kewaunee County, said he has monthly meetings at his farm with agronomists, nutritionists and veterinarians. He considers it his own continuing education.

“With your consultants on your farm, you’re bringing the classroom home… I’m just wowed when I sit around our consultant meeting at the information that comes to that table,” Kinnard said. “It’s the who’s who in agriculture, they’ve all got instant access to scientists.”

Weigel sees the increase in higher agriculture education, including master’s and doctorate programs, as meeting the need for the consultants and scientists that farmers like Kinnard use. Weigel said approximately 50 percent of graduates from his department serve in those agriculture service roles while 25 percent go into farm ownership or operation.

For those farmers that go on to operate their own business, all said a business degree would go a long way on the farm.

“To be successful we all have to be the conductor of the dairy,” Niles said, likening it to a band leader. “You don’t necessarily have to know how to play the violin and play the oboe, but you need to know how to direct the person playing the oboe.”