If Your Feet Are Wet: Legacy of the Public Trust Doctrine

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Growing up as a tourist visiting Wisconsin, I used to hear the phrase, “If your feet are wet, you’re not trespassing.” I remember hearing it while walking along the shores of Chambers Island as a kid thinking it was such a funny rule. Little did I know it was a rule steeped in Wisconsin history and a legacy of the state’s natural resources.

Wisconsin’s public trust doctrine is part of the state constitution and it declares all navigable waters in the state open to the public, no matter what kind of private property surrounds them. That means rivers, streams, ponds and lakes that are deep enough to float a skiff are public.

The doctrine is the subject of many lawsuits related to public versus private rights, including the 2017 trial of the Sturgeon Bay west side waterfront redevelopment. While steadfastly upheld through most of the 20th century, some say the courts have eroded the doctrine’s strength in favor of private rights. With 298 miles of shoreline and even more inland navigable waterways, Door County has much to gain, or lose, from the doctrine.

History of the Public Trust

While the public trust doctrine rests in Article IX, Section 1 of the Wisconsin State Constitution, adopted in 1848, its true origin lies in the original ordinance of the Northwest Territory back in 1787. The language from that ordinance is taken almost word for word in the state constitution.

Hunting clubs surrounding the Horicon Marsh claimed the waterways were private but were overturned when Paul Husting claimed the Public Trust Doctrine opened the waterways for all to use.

“The navigable waters leading into the Mississippi and St. Lawrence, and the carrying places between the same, shall be common highways and forever free, as well to the inhabitants of the state as to the citizens of the United States, without any tax imposed or duties therefor,” said the Northwest Ordinance.

Even then, the concept of free public waterways dates back to the Roman Emperor Justinian, who said the sea, air and running water was common to everyone. That idea made it into the Magna Carta and, finally, common law of the United States.

When the United States got the Northwest Territory in 1787, which included modern day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin, it had only two conditions. First, any new states to come out of the territory must have the same rights as other states. Second, all navigable waterways will forever be free to the public.

Before the doctrine had any strength, it was important to define what navigable meant. Like anything else in state law, that definition has ebbed and flowed with the times.

Early on, when Wisconsin was a champion of water commerce and logging, there was the “saw-log test.” A waterway was navigable if a log could float on it. Today, with recreation such a major part of the public’s enjoyment of the water, it means any kind of floating craft.

The doctrine is now understood to protect any land up to the ordinary high water mark, or the line on the shore where the water typically ends. That ordinary high water mark was a central part of the lawsuit between the Friends of the Sturgeon Bay Public Waterfront and the City of Sturgeon Bay. They debated where the ordinary high water mark was, but no one questioned the mark’s power and legacy in the state.

Public Trust in the Courts

Sturgeon Bay isn’t the first place the public trust doctrine has appeared in the courtroom. It has been tested, expanded and sometimes diminished at various times throughout its history. In fact, the argument by the attorneys in the Sturgeon Bay case frequently cited many of the cases that have historically set the tone of how the public trust doctrine is handled in the state.

The case of Illinois Steel Co. v. Bilot in 1901 is perhaps the most basic strengthening of the doctrine in the courts.

Paul Husting served as a United States Senator from 1915 until his death in 1917. Photo from the Library of Congress.

The City of Milwaukee, during expansion of its harbor, tried to declare portions of the lakebed non-navigable. It then tried to sell those portions of the lakebed to the Illinois Steel Co.

The court ruled, since the language of the public trust doctrine passed directly from the Northwest Territory ordinance to the state constitution while emphasizing the public was the true owner of all navigable waters, the city or state legislature never owned the land and therefore can’t sell it to private landowners.

Just before that, in 1877, it was Olson v. Merrill that determined the “saw-log test.” The government wanted to float timber from a logging operation down a stream that ran through someone’s private land. The court determined that the floating of the logs was in the public interest and thus, as long as a body of water could float a log, it was public.

Perhaps the biggest case to support public recreation on Wisconsin waters happened in the Horicon Marsh in 1913.

Paul Husting was an avid hunter and attorney living near the marshes of Horicon. In the early 1900s, six major hunting clubs in the area ruled those marshes. They each privately owned a portion of land that their members could hunt on. On a brisk autumn day, Husting was hunting on his own small boat in the marsh when a warden with the Diana Shooting Club arrested him and charged him with trespassing. Husting defended himself at the Dodge County Courthouse and before the Wisconsin Supreme Court saying that the waterways were free for access under the public trust doctrine. The courts agreed.

“Navigable waters are public waters and as such they should inure to the benefit of the public,” wrote the court. “They should be free to all for commerce, for travel, for recreation, and also for hunting, and fishing, which are the mainly certain forms of recreations.”

This case went far beyond the economic incentive for the state to preserve public waters for the purposes of commerce and turned Wisconsin into the haven for water recreation that it remains today.

The protection of lakebeds then came to the fore in Priewe v. Wisconsin State Land & Improvement Co.

In 1981, the legislature wanted to drain the Muskego and Wind Lakes and then sell them for private development. A man who owned property on Muskego Lake wanted to keep his lakefront and he sued.

The court held that navigable waterways were to forever stay in the public’s interest and the legislature couldn’t simply sell off the state’s obligation to ensure that.

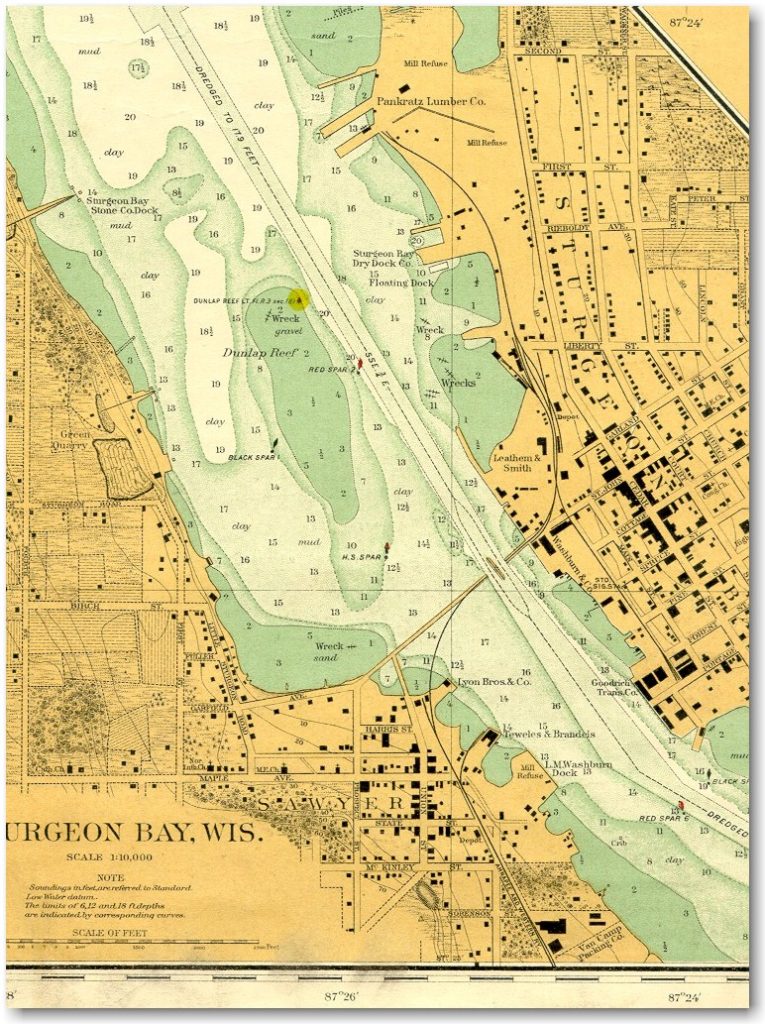

A map from the United States Department of War in 1925 was used during the waterfront trial in Sturgeon Bay. The numbers refer to the lowest water depth recorded, which is at least 2.6 feet below the actual high water mark.

The hallmark case of Just v. Marinette County in 1972 determined a private landowner could not fill in navigable waterways. If so, then someone who lived on a waterway could just fill it in and increase their acreage.

But the public trust doctrine is still being challenged. A case similar to the one in Sturgeon Bay arose in Milwaukee in 2013.

The city sold its old Transit Center site near the lakefront downtown to a private developer who planned to raise a 44-story tower. Old maps show much of the land is on filled lakebed but the court ruled in favor of the development. Much like Sturgeon Bay, it was a battle over the validity of historic maps, but this time the public spaces lost.

In another 2013 case in Rock-Koshkonong Lake, the court narrowly tailored the reach of the public trust doctrine, leaving out wetlands that are in private land next to navigable waterways when setting lake levels that are affected by dams.

“This represents a significant and disturbing shift in Wisconsin law,” wrote Supreme Court Justice Patrick Crooks in the dissent.

The court said since the adjacent wetlands were non-navigable, they could not be considered in the public trust. Some say this was the first time the courts limited the reach of the public trust doctrine.

The shift toward waterfront development paired with the trend of opening up lakeshores to public use creates a tangled battle of development versus preservation. Since waterfront development is likely to continue, so will the importance of the public trust doctrine as Wisconsin’s premier defendant of public lakefront and water access.