Finding the In Between

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Lynn Gilchrist’s art career has traversed the spectrum of the expected and unexpected

The way Lynn Gilchrist talks about her life and art is to describe a series of breakthroughs – or pivots – in her thinking about art. She left a quiet Chicago suburb in 1968 to attend Oberlin, a top-ranked liberal arts college, to major in studio art and art history because she was so fascinated by what was happening in contemporary art. She studied with Ellen Johnson, a powerful force in promoting contemporary art during the 1960s.

“Ellen brought artists from New York City to speak,” Gilchrist said, “and even though we were a little rural Ohio college, New York and Los Angeles seemed to be alive because she went there, and she wrote about the art there.”

The primary goal or requirement in art at that time was that it had to be new: new ideas, new in form, but above all else, new, she said.

“I was so steeped in the time – wild and crazy, cutting-edge art, something different, something with intellect behind the art,” Gilchrist said. “I aspired to be one of those artists, but it’s like, how do you begin? Where do you find the best ideas that nobody’s ever had before? The problem with that is that if you say you don’t want to do it because it’s been done before, if you follow that to its logical conclusion, then you wouldn’t do any art.”

Gilchrist set out to impress a new instructor who was just out of grad school with her concept for an independent study.

“So I’d sit and make these diagrams for possible performance art – we had a big, strong, very contemporary dance-movement group,” Gilchrist said. “So I would draw out some of these ideas.

“I showed him all this stuff, thinking, ‘He’s gonna realize I’m, you know, I’m on my way to being a little more on the hip side,’ and his impression was, ‘You’re really good at drawing. Why don’t you draw?’ That seemed so retro, but it obviously stayed in my mind.

“I remained interested in making art that created some questions rather than predictable answers,” Gilchrist said. “I did do some figurative drawings, but they were large and more about impersonal juxtapositions than about human interactions.

“I also did a lot of ‘drawings’ using coffee grounds, sticks or string; and collages with rubbings using magazine photos and solvents. I did one painting that was a precursor to the many landscapes I have painted for decades. It included Western imagery from our childhood trips and was divided into three sections because a straight landscape would have seemed too ‘boring’ in those days.”

Postcollege life included earning some credits at the California Institute of the Arts and waiting tables in Washington, D.C., where Gilchrist met her husband. She moved with him to his hometown of Sturgeon Bay, got an office job and did a little drawing and painting on the side.

Gilchrist continued to feel stuck between creating pretty drawings that people without an arts background would understand, and the idea of creating work that was more original and challenging. She began to work with an old set of pastels and – inspired by a figure drawing by Mary Ellen Sisulak that was part of the Miller Art Museum’s annual juried show in 1978 – entered her own drawing the next year. She was happy to be accepted.

“It was kind of my breakout in a way – or breaking in – to building a body of work,” Gilchrist said.

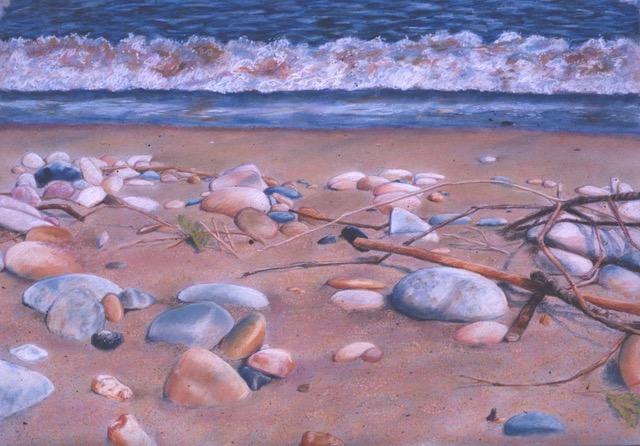

She started doing large pastels of beach scenes from an ant’s point of view – big pictures of small subjects such as the little pebbles on a beach. They proved popular, but eventually she wanted to move on from that medium and subject matter.

“There just came a point where I realized I had never done much actual painting – with brushes and paints,” Gilchrist said. “These pastels were subtle, and I wanted to go bolder.”

By the mid-80s, she was doing representational work: art that represents reality in a more or less straightforward way. She also had a young daughter, was getting divorced and decided to try to earn an MFA with the goal of teaching at the college level.

But, Gilchrist said, “I was doing it so part time with a little kid, so I didn’t last long.”

A discussion with an art professor, however, marked another turning point.

“He pointed out to me that I was acting as if there was representational, or there was nonrepresentational art, and there was nothing in between,” Gilchrist said.

“And I remember going to a show at the Art Institute of Chicago that was somebody’s collection of works on paper,” she said. “I realized that amid some pretty crazy, brazen big stuff, there were also a lot of very quiet, little, sensitive drawings – the kind I had started out drawing. And I thought that if it’s in the Art Institute, maybe there’s something to be said for the whole range from big and bold to delicate, small, personal works.”

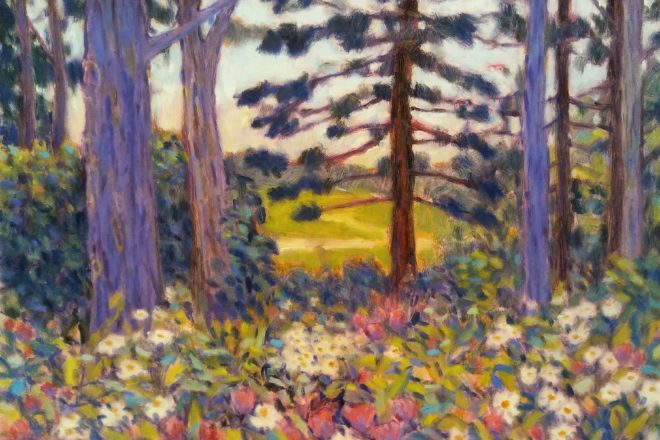

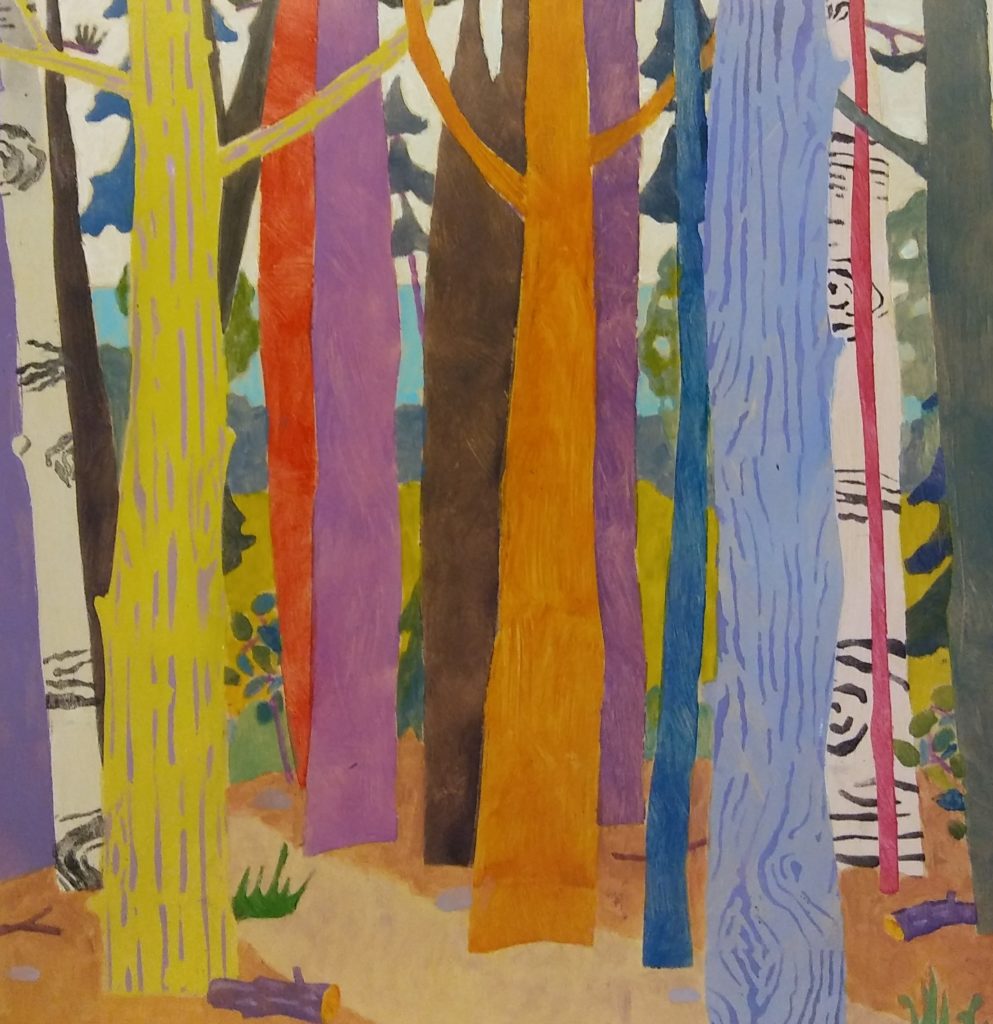

Gilchrist’s work is now a lively representation of real subjects, often depicted with strong color and movement, and her subject matter includes landscapes, still lifes and figurative work. Lately, besides her plein air landscapes, she paints scenes of trees using stencils that she cuts to create clean edges.

After a number of changes in her approach to art, she’s pretty comfortable with where she is now.

“I have been 100 times more productive in the last four years than I was in my four years at Oberlin,” Gilchrist said. “Then, I was so caught up in the studying of art, and I was a little frozen over thinking that what I was doing wasn’t good enough. The result was that I was not very productive.”

This winter, she wants to be more exploratory in her art, “without thinking it is for a specific show or that it has to come out in a certain way,” Gilchrist said. “I want to set some winter challenges for myself – to make things that don’t look like they looked before. What would Black Lives Matter look like without doing people, without just simple narration? Now if I say this, I’m gonna have to stick to it. Next year, same time, you have to check in on me.”