The Fire That Took Williamsonville

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

The Peshtigo Fire, which proved to be the deadliest fire in United States history, approaches its 145th anniversary this fall. On the night of October 8, 1871, between 1,700 and 2,500 lives were estimated to be lost as a result of the forest fires that took place in and around the Peshtigo area, including regions of Brown County, Kewaunee County and Door County.

The origins and pathway of the fire, based on the geography, has had some assume that the fire began in Peshtigo and spread south to the lower tip of the Bay of Green Bay and continued northward to Door County.

However, the tragedy that struck northeast Wisconsin was not one continuous fire that traveled from Peshtigo into Door County. Nor did the fire cross the Bay of Green Bay into the Door Peninsula regions. Rather, it was at least three separate fires, two of which engulfed the western side of the bay and one that began just south of New Franken and continued northward to Sturgeon Bay.

The series of fires, collectively known as the Peshtigo Fire, occurred on the same night as the well-known Great Chicago Fire that claimed nearly 300 lives. The heavily populated city of Chicago, the fifth largest in the nation at the time with 300,000 residents, attracted an outpouring of support through media outlets following the loss of more than 17,000 buildings and 2,000 acres of land leaving an estimated 100,000 residents homeless.

Additionally, both the Great Michigan Fire and the Port Huron Fire devastated the Midwest on the same fateful Sunday of October 8, 1871. Those fires claimed at least 200 human lives in Michigan.

The forest fires that occurred in the Midwestern United States were not merely coincidental. Months of dry and hot weather contributed to ideal fire conditions. Lack of rain over the course of that summer caused many of the swamps in the area to completely dry out. Settlers became increasingly worried, knowing that sporadic fires were taking place throughout the region and causing damage to homesteads, livestock and crops, including countless acres of forests.

Poor land-clearing practices of the time, known as slash and burn, created several smaller-scaled forest fires throughout the drought-ridden region. The slash-and-burn practice was a method of agriculture where vegetation was cut down and burned off before sowing new seeds. This method was used to clear and transform forested lands to prepare them for farming.

What caused the forest fire to become widespread were strong winds that swept through the Midwest. A large, low-pressure system that took place in the western-half of the country coupled with a high-pressure system over the eastern United States converged in the upper Midwest to create winds that reached speeds upwards of 32 mph. The strong winds that contributed to the spread of the fires culminated into a larger conflagration.

The wildfires that began south of New Franken spread north and passed through thousands of acres and several towns and settlements. The fire raged through the towns of Union, Brussels and Forestville. It threatened to continue north in the towns of Gardner and Nasewaupee, which would eventually lead into Sturgeon Bay.

However, a smaller-scaled fire that occurred a month prior in the towns of Gardner and Nasewaupee proved to be a saving factor for Sturgeon Bay. Due to the previous blaze that cleared the natural area, the fires on the night of October 8th were slowed due to having little combustible vegetation to further fuel the blaze.

In the fire’s northward path of destruction was the settlement of Williamsonville, just northeast of Brussels, that was essentially wiped off the map due to the devastation of the Peshtigo Fire.

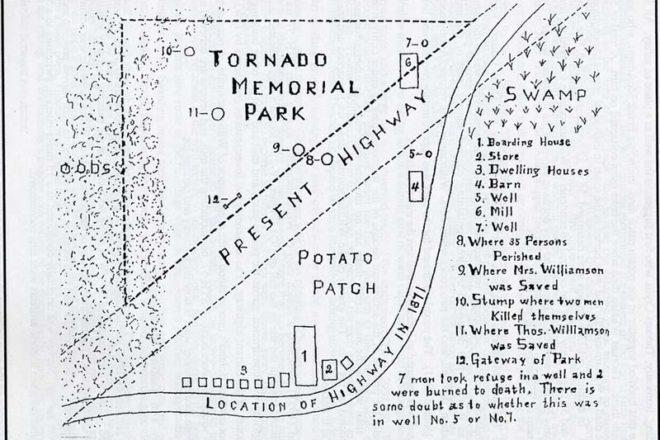

The village of Williamsonville, also known as Williamson’s Mill, had 77 residents and covered an area of less than 10 acres that ran alongside the highway’s route in 1871. The village was founded by two brothers, Fred and Tom Williamson, both of whom ran one of Door County’s largest shingle mill operations. Nearly all of the residents were members of the Williamson family or were employees of the mill.

The buildings alongside the highway consisted of eight homes, a boarding house, a store, and a blacksmith shop. The mill and storage barn were separated from the rest of the buildings. The highway that ran along the settlement was routed slightly differently than the current roadway today.

The forest fires that raged through the eastern side of the bay on October 8th consumed Williamsonville in its path. The greatest loss of life on the eastern side of the bay occurred there.

Of the 77 Williamsonville residents, all but 17 perished in the fires. Despite initial attempts to save themselves and their possessions, the worst fears became a reality as their settlement soon lay in ruin.

What proved most challenging in attempts to escape the firestorm was the rapid advancement of the fires. In addition to the dry weather conditions, the winds over northeastern Wisconsin produced what was described as “tornadoes of fire,” known as fire vortices. These vortices occurred in and around the main fire and contributed to the acceleration of the fire. Many eyewitnesses, never having seen such chaos and horror brought about by the fire, had believed judgment day arrived.

Sixty Williamsonville residents lost their lives in the Peshtigo Fire. Tales of desperate efforts to survive were true for all 77 souls affected. Seven men had sought refuge in a well to escape the inferno, where five of the men survived. The speed of the fire consumed several men who attempted to outrun the blazing firestorm. Some residents used wet blankets to cover themselves from the flames. Most did not survive. In a potato patch, 35 individuals perished, huddled together hoping the flames would pass by the cleared land. Two men, suffering from the intense agony of the fires, resorted to ending their own lives by beating their heads upon a stump.

Those 17 that did survive did not do so unscathed. The majority suffered severe burns to their feet, hands and eyes. One individual lost both legs as a result of the fire. These saddening accounts were not exclusive to Williamsonville. Throughout all regions affected by the Peshtigo Fire, similar events and horrors unfolded.

The somber end that came for 60 lives and the tragic affects, both physically and emotionally, that remained with the 17 survivors marked the end of Williamsonville.

The settlement of Williamsonville was not rebuilt. No more than seven years later, an 1878 map of Door County marked the site as “Tornado,” where Williamsonville once stood. The Peshtigo Fire transformed the region’s economy. Lands that once served as harvesting grounds for lumberjacks soon became rich farmlands for crops.

Although news of the Peshtigo Fire was slow to reach national news outlets, partly due to being overshadowed by the Great Chicago Fire and also due to a lack of communication via telegraphs from the region, word soon spread throughout the nation.

National and statewide relief efforts helped the region begin its recovery from the destruction of the fires and helped those who survived rebuild their lives.

Tornado Memorial Park, established in 1927, now serves as a permanent reminder of those who were affected by the Peshtigo Fire in former Williamsonville. The well that saved five of the seven men still stands today, marked by a wooden arch with an inscription of their survival. Two bronze plaques, located under the Tornado Memorial Park sign, memorialize the lives both lost and affected by the most devastating forest fire in our nation’s history.

Sources: “Tornadoes of Fire at Williamsonville, Wisconsin, October 8, 1871,” Joseph M. Moran and E. Lee Somerville in Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters (Volume 78), Carl N. Haywood, 1990

“The Great Fire of 1871, Door County, Wisconsin” in History of Door County, Wisconsin: The County Beautiful (Volume I), Hjalmar R. Holand, 1917