The Remarkable Life of Artist Gerhard Miller

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

For most boys, growing up in Sturgeon Bay in the early years of the 20th century – whooping through the woods, skating, sailing and swimming – being felled by polio at age 10 would have been a tragedy. For Gerhard Carl Friedrich Miller, once the agony of recovery was over, his illness led directly to success in a career that spanned nearly 90 years.

When he was diagnosed in October 1913, the doctor told his parents he didn’t expect their son would ever walk again, but he underestimated the family’s determination and tough love. Before leaving for work each morning at the Miller Clothing House, Gerhard’s father put the boy on a blanket on the floor, telling his wife that Gerhard must learn to turn over alone. By spring, he was riding a tricycle. Then Adolph Miller heard of the McLean Sanitarium in St. Louis. He borrowed from every source possible to amass the $8,000 it would take for Gerhard and his mother to stay there for six months.

As an adult, Gerhard described the torture he endured, including a machine called “the rack” that stretched his crippled left leg, and the operation, without general anesthetic, to sever the tendons in his twisted foot and ankle. To help take his mind off the pain, his grandmother taught him to crochet. Two hundred dishrags later, Gerhard put down the crochet hook and picked up a pencil. Pictures of the Door County he loved filled his head, and he discovered he had a remarkable talent for putting them on paper. When he returned home, two years behind in school and no longer able to keep up with his friends’ games, drawing became his escape – something he could do that others could not.

In 1927, when his father became seriously ill, Gerhard dropped out of his junior year at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, where he’d been studying business, and came home to run the store.

In 1929, he married Edna Knudson. They honeymooned in Europe for three months, returning with $4.60 and a love of Norwegian architecture that influenced the home they would build years later. He’d begun to paint by this time, working in oils at an easel his father helped him build. During all the years he managed the family business, he found time before work, at lunch and in the evening to pursue his passion, reading every art book he could find and practicing what he learned. He was in his 60s before he had an art class, and a professional who evaluated his work said that being self taught and having remarkable self discipline were what enabled him to develop his unique style of imaginative realism.

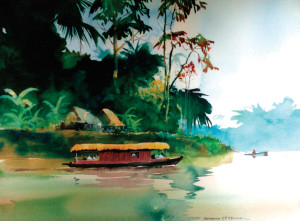

Gerhard’s paintings decorated the walls of their home for some time before he sold his first one for $15. As sales increased, part of the money went for more art supplies, and the rest went into a “travel kitty.” The family’s second trip to Europe included their children, David and Margaret. As the money for paintings began to flow in, the trips became longer and more frequent. Gerhard used to say he’d pedaled twice around the world on his stationary bicycle, and his actual travels took him to 44 countries. He sketched and painted his way through all of them.

When, in 1936, Gerhard felt he could afford the Norwegian dream house he’d designed, he found that he could build it himself, with minimal help, for just over half of the carpenter’s bid, and he did – learning to carve and plaster to add special touches. It was too expensive to have the wrought iron chandeliers he’d designed made, so he created them, too, borrowing the well driller’s forge and the plumber’s shears.

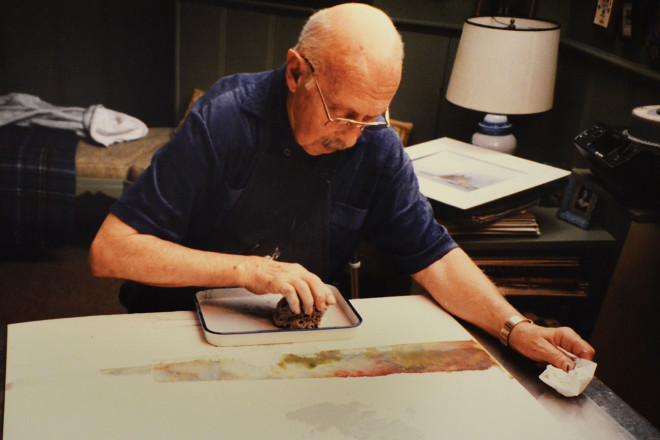

During World War II, as the population of Sturgeon Bay burgeoned with ship builders, work at the store was extremely heavy, cutting into Gerhard’s painting time. Because working with oils required hours spent cleaning brushes and palettes, he switched to watercolors. He said the medium had a “sporty” quality. Soon his paintings were selling well, not only in the little gallery beside his home – said to be the first in Door County – but also in two galleries in New York.

Gerhard was a close friend of Jens Jensen and for eight years traveled to The Clearing to teach weekly art classes. He was always generous with his time to work with aspiring artists. His life was complete and fulfilling. Then, in 1956, Edna died suddenly, and he said later that his devastation struck to the core of his entire world. For the first time in more than four decades, he had no inspiration to paint.

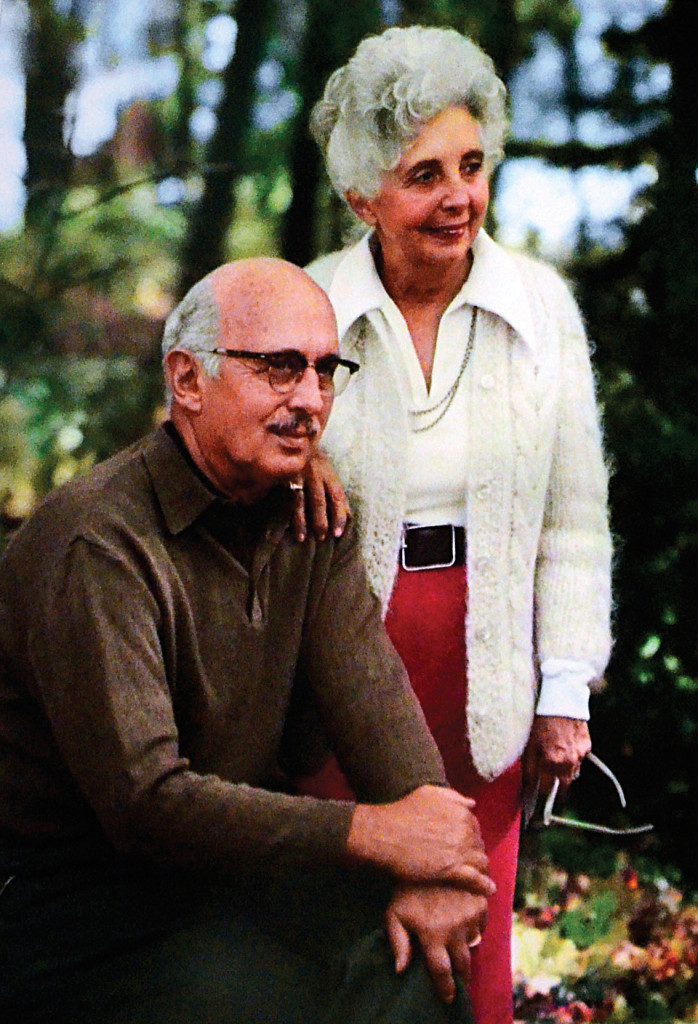

His spirits improved after a winter in the south, and he returned to Sturgeon Bay to sell the store and devote full time to his painting. One of his first commissions was from a woman in Milwaukee, represented by an interior decorator named Ruth Morton, whom Gerhard and Edna had met through business some years earlier. Ruth had studied art in her youth, but after two years realized she would never be a great painter. After she and Gerhard were married in 1957, he often told friends that he had been twice blessed to have shared his life with two wonderful women and quipped that Ruth, who had studied art, handled the family business, while he, who had studied business, was the artist.

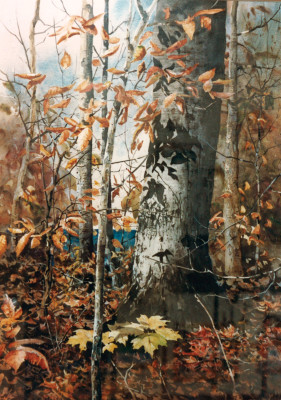

By 1966, Gerhard’s work was becoming nationally known and Ruth, a talented writer, was working on her second textbook on interior decorating. Both received fellowships for study at the Huntington Hartford Foundation in California. Although they were eligible for six months’ residency, their lives were so busy that they requested to stay for only two. But it was during these months, in the first art class Gerhard had ever taken, that his career took a major turn. He was introduced to egg tempera, the most ancient painting medium known. It became his favorite for the rest of his life. And, it paid off immediately, when Vincent Price, commissioned by Sears Roebuck to organize an art program, bought 25 of his paintings. Already a member of the prestigious American and Wisconsin watercolor societies, Wisconsin Painters and Sculptors and the Audubon Artists, Gerhard’s fame spread through exhibits in several states, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The Moravian College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, awarded him an honorary Doctor of Humanities

Although Gerhard loved to travel, his heart was in Door County, and as his success grew, he wanted to give something back. While on a trip to Italy in 1970, he thought of creating an art center in the new county library being planned in Sturgeon Bay. That first room, with space for only 30 paintings, was funded entirely by the Millers, on condition that the public donate money to build the library. The Ruth Miller Mezzanine was added in 1983, and the final expansion in 1995 doubled the exhibit space. As a surprise, a wing was named for Gerhard.

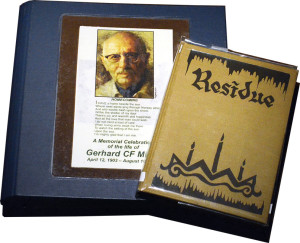

Even in his later years, his lifelong work schedule never varied: His little gallery, steps from his back door, was open from May to September. In the fall, he “warmed up his hands” by doing 30 to 50 small pencil sketches, followed by 30 to 50 small watercolors. After the holidays, he did 16 to 18 full-sheet paintings – and framed them all before May. Ruth Miller died in 2001. Gerhard was still painting when he celebrated his 100th birthday, just months before his death on Aug. 16, 2003.

The dean of Door County artists achieved fame far beyond what the boy with polio could have imagined. He traveled the world. His work, including six self-published books, brought joy to many. And he gave much back to the county he loved.

He had dozens of prominent friends, but he never lost touch with the common man. One day while he still worked in the store, a customer came in, carrying his son on his shoulders. Gerhard asked why the boy was not walking. The man answered that the child had survived polio, but could no longer walk.

“I had polio,” Gerhard said. “I learned to walk again, and you can, too. The day you walk in here, I’ll buy you the finest bicycle in Sturgeon Bay.”

Months later the jubilant boy hobbled through the door. He and Gerhard limped out together in search of a bicycle.

Miller Art Museum Fulfills Artist’s Dream

It was the dream of Gerhard and Ruth Miller to make art accessible in Door County year round, and the Miller Art Museum fulfills that dream.

The permanent collection of 617 pieces, representing 198 Wisconsin artists from the early 20th century to the present, is displayed in the museum’s main room and in the Ruth Miller Mezzanine on a rotating basis, changed every seven weeks. The

Gerhard CF Miller Wing displays 100-plus of his paintings on a rotating basis. Many came directly from Gerhard, who every year donated one or two that he considered his best work.

The Millers also wanted the museum to be educational, and on the second Thursday of each month from September through June it hosts a free lecture or create-it-yourself program. There are also classes for children and adults, tours, a unique gift shop and outreach activities.

Bonnie Hartmann and Deborah Rosenthal are the museum’s director and curator, respectively. There are three part-time employees and 135 volunteers, without whom, Hartmann says, “We could not possibly survive.”

Information:

Address: 107 South 4th Ave., Sturgeon Bay

Phone: (920) 746-0707

Website: www.millerartmuseum.org

Hours: Open Monday 10:00 am to 8:00 pm.

Open Tuesday through Saturday 10:00 am to 5:00 pm.