‘Good Seeds’ Author Brings Menominee Indian Food Memoir to Door

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

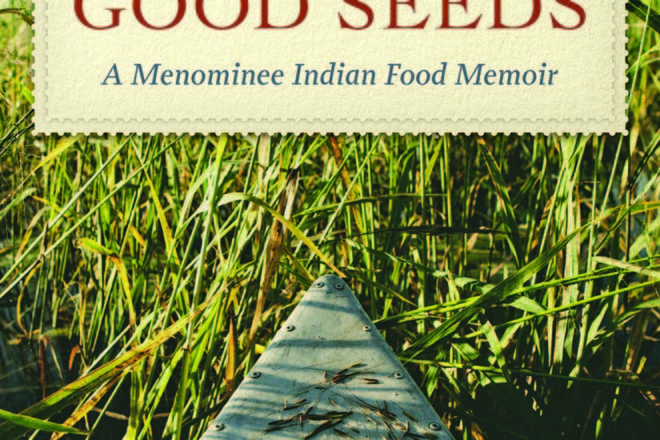

Because my Wisconsin dairy farm family foraged for hickory nuts, morel mushrooms, and wild blackberries, I read with interest Thomas Pecore Weso’s new book, Good Seeds: A Menominee Indian Food Memoir. A member of the Wisconsin Menominee Nation, Weso takes readers through an indigenous culinary history of his people, every chapter devoted to a different food. Each begins by citing relevant historical text and then draws upon the author’s experiences as a youth, concluding with pertinent recipes. The title Good Seeds is taken from manomin, the wild rice that gives the Menominee Indians their name.

“I want the Menominee and others to understand how interrelated we are,” Weso said. “In Wisconsin I grew up influenced by the German, Polish and Scandinavian people as well as Forest Band Potawatomi and Ojibwas.” While they had separate communities, they drank at the same bars, he pointed out, hunted deer and fished.

“I thought cottage cheese was an Indian food,” he said, “and the same with sauerkraut and pickled pigs’ feet.” He finds that “the mystery is in the intangible, distinct essence of each community with its traditions that make us all adapt the same materials in different ways.”

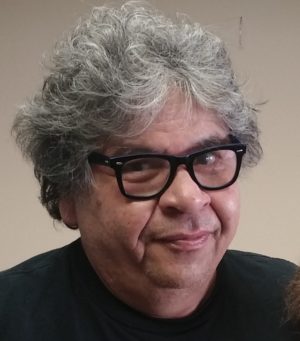

Thomas Weso

Weso, who holds a master’s degree in Indigenous Studies from the University of Kansas, earlier attended and later taught at the Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas. Coincidentally, his grandfather, mother, uncles and aunts, along with his daughter all studied at the same institution. Now he teaches at the Kansas City Kansas Community College.

The book is a culmination of the memories he shared with his wife about his life on the reservation. She made typescripts, and when the couple noted that most of the stories were about food, Good Seeds seemed the perfect way to share them with others.

“Recipes reflect the food environment,” he wrote, “as well as how people are interacting with that environment, which is food culture.” He asked students at the beginning of a term to bring in their family chili recipes and then they compared them in class to illustrate this concept.

Four people appear as central characters in Weso’s Good Seeds. One is his grandmother Jennie whose story opens the book in the chapter “Fire: Grandmother’s Morning.” While she, like her husband, had “attended assimilationist boarding schools where they learned about the dietary culture of the larger United States,” the couple nonetheless “perpetuated ancient hunting, gathering, farming, and storage practices from the earliest Algonquin woodland dwellers.”

She was the one who “made fire,” rising at 4 am every morning to prepare breakfast for an extended family, a meal that might include bacon and eggs, or fish, squirrel, and partridge. She was the matriarch devoted to feeding her family. “I never saw her sit down and eat a meal in peace,” Weso recalled.

His grandfather Moon “was considered a medicine man,” Weso said, and “his morning prayers were the foundation for each day’s meal.” The chapter “Prayer: Grandfather’s Dreaming” is devoted to him, “one of the last of the old Indians from that era before substantial intermingling of cultures,” speaking his native language fluently, and serving as a “cultural go-between” and “a public leader among whites.”

“Part of Grandpa’s teaching was gardening,” Weso added. The family always had a garden where they could see their efforts bear fruit. “That reward also had a spiritual aspect.”

Uncle Buddy, Weso said, “was the closest thing to a father that I ever had.” While he was “smart, brave, loyal, educated,” he was a “flawed hero” of World War II who could not forget the horrors of the white man’s wars, the months he spent guarding German prisoners at Auschwitz.

In the chapter “Blackberry Wine” Weso tells of the time his uncle purchased six shiny new garbage cans, persuaded kids on the reservation to pick blackberries for him, and made wine. “People talked about the 330 gallons of blackberry wine for years afterward,” he said. “The batch lasted the reservation the entire summer.”

For those interested, the recipe is in the book.

Wallace, the family’s hired hand, appears in the chapter “Partridge.” Weso remembers hunting partridge eggs with Wallace, breaking the shells and eating the egg raw.

A Navy veteran, Wallace had a tattoo of a bare-bosomed grass-skirted hula girl who danced when he flexed a muscle on his arm, a novelty for young Thomas. Wallace taught the boy how to whistle and how to crack a deerskin bullwhip.

When Wallace quarreled with Grandmother and moved in with another relative, “He left me with experience of how to be a Menominee man,” Weso said.

Speaking of his family’s cooking, Weso explained “traditions continued side by side with more modern practices.” He points out that “one of the only good things which white people gave us was the frying pan – every thing was cooked on the stove top, long, low heat.” But while some of the recipes are relatively conventional, others seem exotic, for example, roasting porcupine, beaver tail, or bear, sometimes with barbeque sauce, or preparing milkweed, dandelion greens, or a wild rice casserole.

He includes anecdotes, such as seeing staggering bears drunk on the alcohol content of rotting apples. He recalls an experience of taking his young daughter fishing, helping her with her first catch, and then cooking it for her on the spot on a portable grill. And he recalls a local connection, when his family picked cherries at the Reynolds Orchard in Door County.

Readers have enjoyed this informal study of a culinary culture, and appreciate the extensive bibliography included in the book. For those who would like to meet the author, Weso will be at the old Calvary Church on Highway 42 in Egg Harbor (the old white, wooden church directly on the highway next to Village Cafe) on Oct. 14 at 7 pm for a book talk and readings, followed by a book signing.

Good Seeds: A Menominee Indian Food Memoir, by Thomas Pecore Weso, 122 pages, the Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2016.