Heart in Sound: Billy Triplett Found a Home

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

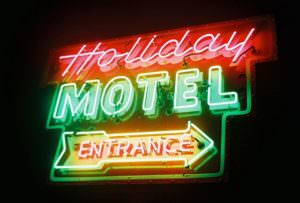

When I sat down in July to talk with Billy Triplett about his life in music and what brought him to the Holiday Music Motel in Sturgeon Bay, there was no way to know that Billy had only 24 more days to live.

As we were doing the final edits for this fall issue, word came that Billy suffered his fifth and final heart attack in his room at the Holiday Music Motel in Sturgeon Bay. He was 56. Here is his story.

After decades of touring the world as soundman and get-’er done guy for individuals and bands as diverse as James Brown, Joe Walsh and James Gang, Robert Cray, the Goo Goo Dolls, Pat Benatar and Prince, to name just a few of his many musical associations, Billy Triplett accumulated a million stories of life in the rock ‘n’ roll fast lane.

Not every tale was the expected rock ‘n’ roll excess. Sometimes it was a story of trying to find some degree of normalcy in a very abnormal life.

Because he was born with an extra helping of empathy, which allowed him to read situations quickly and react to them appropriately, he was recognized as more than the sound engineer.

“Being able to work with people and dealing with artists, it’s a whole other level, especially at a top level,” Triplett said. “Prince, he’s probably the top on my list, well, him and James Brown, side by side of figuring out how to deal with somebody who didn’t want to deal with anybody. These guys are brilliant geniuses. They have no time for what they think is stupid stuff. You had to figure it out. If you had to go to the source and ask him, you’re probably going to get fired, and Prince fired people on a daily basis. If you open your mouth, you better have a very good idea or suggestion. That’s what I was taught.”

Triplett’s last big tour was with Pat Benatar, who grounded herself on tour by doing laundry with her own washer and dryer, which the crew had to set up at each stop on the tour.

While the rest of the crew grumbled about it, Billy understood Benatar’s need for some semblance of normalcy as she toured.

“Instead of being a rock star, she’d be doing laundry,” he said.

Despite the mutinous grumbles from others, Triplett made sure the washer and dryer were set up for her so everyone would have a good concert that night.

“Somebody’s paying $80 to $100 a ticket, there better be entertainment and it better be magical,” Triplett said. “You try to make that happen every night, even when someone in the band’s sick or something’s not right, you try to make that magic happen, that illusion. That’s our responsibility, especially in production.”

That ethic placed a ton of stress on Triplett over the years, especially when he moved from being the sound engineer, to head technician, to production manager and tour manager.

“I’d get hired in the middle of tours, never in the beginning, but when everybody was mad and they fired their sound engineer and tour manager,” Triplett said. “The tours would be ready to mutiny. The band ready to kill. That’s when I’d get flown in. The first day, everyone hates you. You know that right off the bat because you’re the new guy and no one can trust you. So I just do my thing and show them, ‘Wow, he can mix.’ That’s the first thing you have to prove. If you can figure out how to make things run a little faster and keep everyone organized, you’re in. They’d bump your pay up with the extra work, but you’re doing four people’s work. It’s a heavy weight to bear when you’re responsible for the tour.”

In 2006 Triplett had his first heart attack.

“It laid me up pretty good,” he said, “but I got back on my feet and went out on tour with the James Gang. I was doing other tours on the side, as tour manager and sound guy, taking care of bands and crew guys. A lot of stress. And I had another heart attack. That pretty much wiped me out because I had no insurance.”

He recovered from the second heart attack but was broke. He had only one choice – he had to hit the road again. That’s when he signed on for the Benatar tour. After a year-and-a-half in that position, Triplett had his third heart attack.

“It was the stress getting to me. The doctors were telling me, ‘You can’t tour anymore’,” he said. “But that’s all I did – tour, tour, tour. I never saw the stress. It was a vicious cycle. You go out on the road with all this stress, and stress is a killer. I never realized that.”

What’s a man to do when it appears he has reached the end?

* * *

Billy Triplett got goosebumps when he recalled the moment he knew he would spend his life with music.

He was 18, in his hometown of Kallispell, Montana, “just a stupid kid who listened to whatever pop-rock was on the radio,” he said.

Triplett was about to leave home to pursue a course of study in film and television when someone told him about a guy who had recently moved to Kalispell from Los Angeles and had built a recording studio in his home.

“I went to this guy’s home and he opened his studio for me,” Triplett said. “It was an amazing control room. He played Bob Marley Exodus on a very, very expensive sound system, and I heard the bass. I’d never heard the bass before. It was so clear you could hear the shakers. He opened my mind to music that was so expanding. I knew at that moment, this is my life. I never did anything else.”

Instead of going away to school for film and TV, Triplett bugged the guy into taking him on as a raw but eager student of the art of sound.

“At first, he said no, he couldn’t teach me. So I just kept showing up at his door. Every day I would knock on his door. After about a week of kicking me out, he said, ‘You’re never going away, are you?’ So he took me in, trained me and taught me how to hear. He would buy every record that was ever reviewed and we would listen to them. Why do they say this is a great record and what is great? Not only was it production that was great, it was all about performance and the artist.”

Triplett spent two years under the wing of the relocated Los Angeles soundman before setting up his own studio to record local bands and touring bands that passed through Montana. In 1979 he moved to Portland to pursue a studio recording career in that growing music hub.

Then he got a call from a pal in Missoula who had started a live sound company and was booked to do a Maynard Ferguson concert at an auditorium in Spokane, Washington, and Maynard was hot at the time on the back of the Rocky theme. But his pal couldn’t make the gig and was worried that it would ruin his business. Couldn’t Billy do the gig?

“I don’t do live,” Billy told his friend, but his pal needed help.

“So I go down there,” Billy said. “Had to strap four Yamaha boards together because there weren’t boards big enough then. It was the worst night of my life. I was soaked with sweat. It was horrible trying to mix all these horns in this horrible concrete room. I got done and sat down and was shaking my head, saying to myself, ‘I will never, ever mix live sound again.’ And then the tour manager came over and said, ‘That was really good. Want to finish the tour with us?’ That’s when I got into live sound and what I became known for. I can mix in difficult conditions on difficult gear.

“I do guerrilla recording. I record anywhere. It’s about the performance and the source sound. If you’ve got a great source sound and performance, just get it to the machine. Too many people try to EQ and change it [“EQ” stands for “equalizer,” which are controls used to adjust the tonal characteristics of the signal after it arrives in the mixer from the source]. If you have to do all that to it, there’s something wrong with the source sound.

“I got hired by bigger sound companies to go out on smaller tours of the northwest and California. Once you start working, it becomes a clique. They found out I was pleasant and wasn’t too hard to take care of. Then they found out I could lead lost children, and that was the end of my life.”

* * *

The prognosis is not good as Billy recovered from his third heart attack. Going on tour again was not an option.

“I was really, really broke, and not much of a future, either. I can’t go out and do what I do. What is it worth being around?” he said.

Triplett was living in Laguna Beach, California, at the time. A drummer friend by the name of Wally Ingram, former drummer for the band Timbuk 3, was telling him about an event he had been a part of in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. It was the third Steel Bridge Songfest.

“He was telling me all about Steel Bridge 3,” Triplett said. “He kept telling me about Chris Aaron. He said, you two should really meet.”

Guitarist Aaron was doing the recording for the week of songwriter sessions at the Holiday Music Motel that precede every Steel Bridge Fest.

The two hooked up when Aaron was visiting Laguna Beach.

“I went into a club because my neighbor was the drummer of the house band. Chris was on stage jamming with them. He came looking for me and Wally kind of gave him an idea where he might be able to find me,” Triplett said. “Chris was really involved in the fest and the motel. He said, ‘You’ve got to talk to pat [mAcdonald].’ He put me on the phone with pat, telling him my situation, that I wasn’t going to be able to tour any more, no insurance, bad health, broke. Pat said, ‘Sure, come on out.’”

Triplett flew to Milwaukee and worked with Steve Hamilton of Makin’ Sausage recording studio to help mix the 4th Steel Bridge CD.

“After my mix on that, I went back to California,” Triplett said. “They invited me to come back and do Steel Bridge 5 [in 2009]. The motel had suffered a fire and been closed down for two years. When I first got here, I didn’t know if they would be able to pull it off because there wasn’t even a bed or piece of furniture. The bottom floor was still under construction, but they were able to open the top floor. I put a studio on the first floor in two rooms on the very end. That’s how it all started. Then they asked me to stay and everybody kind of accepted me.”

“The engineers are an important part of the format,” said pat mAcdonald, creative director of the Steel Bridge Songfest. “We are somehow weirdly blessed with Billy and Steve both. They are people of infinite patience and consistent positivity. I’ve been in a lot of recording situations with a lot of engineers, and I’ve seen a lot of recording engineers throw little hissy fits. I’ve seen real pros, too. But there’s something about working with these guys that makes people feel good. They don’t just have the technical side of it, Billy has a special way of making people feel good. He’s got a real talent for it, making people feel comfortable and not interfering with the creative process, letting it happen. That’s a real art.”

In 2009, Triplett moved to Sturgeon Bay for good, residing at the Holiday Music Motel. The last week of October each year features another original music project at the Holiday Music Motel, Dark Songs. A couple days after the 2009 Dark Songs, Triplett had his fourth heart attack.

That’s when friends he made here helped him get health insurance. “They helped me go through all the paperwork,” he said. “Finally I got early retirement disability and now I’m on Medicare. It saved my life. I made a lot of money, but I also paid a lot of taxes. That’s why they let me do this at 55.”

Triplett said his doctor had him on a strict regimen that had improved his health. “I’ve got a new hip. They put a bunch of stents in my heart. I’m getting better and better and better. Wasn’t even supposed to be here.

“The real cool thing is to come out here, not only did everyone accept me, broken, they helped me get better so I can do this here. It’s pretty cool. Then to have the excitement back in your life. That’s the thing about Steel Bridge. It’s so big here. It finally won over the town. There were a lot of bridge haters, and festival haters too, but now they say it’s the best weekend of the year. It’s for the community. That’s what I love about pat, man. He and melaniejane just give to the community. People don’t know about it because they don’t broadcast it,” Triplett said.

“You can’t describe the magic that happens in this building when you get that many creative people in the building and everyone’s focused on writing songs. It’s magical. You sit here and the energy just vibrates in the hallways. People use their hearts here. That’s why the energy is so good for me. It brought me back to life. It gives me a reason.

“That’s the joy of having music still in my life. I was in really bad shape. I would not be here today if it wasn’t for the Holiday. I really wouldn’t and I am still learning. That’s the best part. They push me past the bounds now.

“Fitting that I end up in a motel. I’m strangely attracted to that.”