Heroes of the Storm: U.S. Life-Saving Stations Rescued Many People in 130-Year History

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Bob Desh retired as a captain after a 36-year career in the Coast Guard, then served as executive director of the Door County Maritime Museum. He is also a former executive director of the Foundation for Coast Guard History and presently serves on the Museum Exhibit Advisory Panel for the National Coast Guard Museum, scheduled for construction on the waterfront in New London, Connecticut. A long-time maritime and Coast Guard history buff, Desh shared his knowledge of the Coast Guard’s predecessor, the U.S. Life-Saving Station, at a recent meeting of the Door County Historical Society at the Lodge at Leathem Smith.

The 130-year history of the life-saving stations had its unlikely beginning in 1785 as the Massachusetts Humane Society. It pioneered the concept of establishing shore-based structures to be used by shipwrecked mariners who were able to make it to land. These little huts, called “houses of refuge,” held food, candles kindling and fuel, but no boats. They were situated near busy ports, and left large sections of the coastline without lifesaving equipment.

In 1848, Congress appropriated $10,000 for surfboats, rockets, carronades (line-throwing guns) and other necessary apparatus for the better preservation of life and property from shipwrecks. It was a start, but it was limited to the coast of New Jersey between Sandy Hook and Little Egg Harbor. On Jan. 12, 1850, a great storm struck that area and wrecked many vessels. Because there was a station at Squan Beach with a crew and equipment, 201 of the 202 people on the sinking Ayrshire were saved.

A crew displays their long oars. Submitted.

In subsequent years more stations were added, with nearly two-thirds in New Jersey and New York, but the crews were voluntary, and there was no standardization of regulations or practices. In 1871, Congress appropriated $200,000 to create a life-saving service under the Treasury Department to employ crews of paid surfmen and to build new stations where needed. Seven years later, Congress created the United States Life-Saving Service, with Sumner Increase Kimball as general superintendent.

The Life-Saving Service used two types of boats – lifeboats and surfboats. A lifeboat was too large to be launched in the surf. It was either kept in the water or launched from rails. A surfboat was carried on a cart and launched from the beach by the life-saving crew.

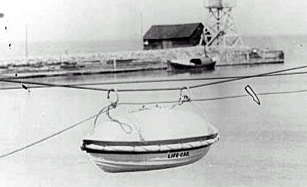

Equipment for rescues included cork lifebelts, a heaving stick and line, a line-throwing Lyle gun and a “faking box” for organizing the shotline to keep it from tangling, a sand anchor, shovels, a breeches buoy or life car, a Coston flare and a cart for hauling all the items, pulled to the beach by a horse or the crew. The life car, that looked like a small submarine, was especially interesting. It had holes to let in air, but little water, and could carry up to four people, who lay down inside. Many, however, refused to get in for fear of drowning.

This boat on a rope was known as a lifecar. Submitted.

Forty-one life-saving stations were established on Lake Michigan, including one on the Northwestern campus, crewed by college boys. Door County had three stations – the Sturgeon Bay Canal, established in 1886, and Baileys Harbor and Plum Island, both established in 1896.

On Oct. 10, 1895, lifesavers from the Sturgeon Bay Canal Station No. 288 rescued the crew of six from the schooner Otter shortly before it went to pieces in the surf on Whitefish Bay. Photographer William shot the rescue for the Advocate.

The Baileys Harbor Lifesaving/Coast Guard Station on what was then called Station Road (later Ridges) was a major part of life in Baileys Harbor until 1948, when it was closed “because of inadequate lake traffic.” It was manned by a captain and six surfmen. Local men, including those from the Anclam, Hickey and Levanger families, were favored for hire, because they knew the lake and the weather. Through June 1935, the station responded to 465 calls for assistance. The most spectacular was the rescue of 15 men from the stranded steamer Philetus Sawyer on Oct. 27, 1916.

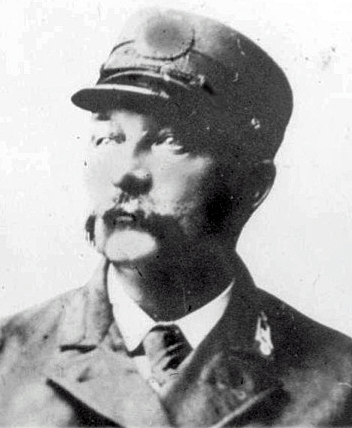

The Gold Lifesaving Medal was awarded to life-saving crew members if the rescue or attempted rescue was made at the risk of his own life with evidence of extreme and heroic daring.

Frederick Hatch was the only two-time recipient of a gold medal lifesaving award. Submitted.

Frederick Hatch, the only two-time recipient of the Gold Lifesaving Medal, was awarded his first medal in December 1884 for his actions as a surfman at the Cleveland Life-Saving Station for rescuing those on board the schooner Sophia Minch. Deciding that a surfman’s job was too dangerous, he requested a new assignment. Ironically, he was awarded his second gold medal in 1891, for rescuing those on board the schooner Wahnapitae, while serving as keeper of the Cleveland Breakwater Lighthouse.

Capt. John Anderson, a native of Ellison Bay, received a gold medal for outstanding bravery in rescuing 17 men from he wrecked steamer H. E. Runnels in Lake Superior in 1919. He started the Plum Island Station and went on to serve 40 years in the Coast Guard, helping to save 4,700 people from drowning in Lake Michigan. His only son, John, Jr., died in the torpedoing of a U.S. ship in 1942, after rescuing seven shipmates.

Ingar Olsen, appointed keeper of the Plum Island Life-Saving Station No. 290 in 1896, had been awarded a Gold Life-Saving Medal while a surfman at the Milwaukee Life-Saving Station in 1893.

Other outstanding recipients of Gold Life-Saving Medals included Joshua James, who initially joined the Massachusetts Humane Society. As keeper of Point Allerton Station, he was credited with saving more than 540 lives in his career. He and his crew received their gold medals for saving 13 lives on the schooners Gertrude Abbott and H.C. Higginson in November 1888.

Surfman Rasmus Midgett, stationed at the Gull Island Life-Saving Station in North Carolina, single-handedly rescued ten people from the grounded ship Priscilla in 1899.

Ingar Olsen served on Plum Island beginning in 1896. Submitted.

The Pea Island Life-Saving Station, located on North Carolina’s Outer Banks, was manned by an all African-American crew in 1896, when they rescued nine people, including the captain, from the wrecked schooner E.S. Newman. They received a commendation, but no medals. Posthumous Gold Lifesaving Medals were belatedly awarded to them a century later, after urging by the descendants of the men who had been saved.

The Evanston crew, all students at Northwestern University, earned their gold medals by saving the entire crew of 18 from the steamer Calumet as she foundered in a blizzard on Thanksgiving Day, 1889.

Crewmen from the Kill Devil Hills Life-Saving Station in North Carolina received gold medals for assisting Orville and Wilbur Wright on their first flight on Dec. 17, 1903. They helped carry the plane to its starting point for each of the three subsequent flights on that day. Surfman J.T. Daniels snapped the photograph which proved the first flight of a powered “heavier-than-air” machine.

In 1915, Congress passed an act that combined the U.S. Life-Saving Service and the Revenue Cutter Service (that had been established in 1790 upon the recommendation of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton to serve as an armed customs enforcement service) to create the Coast Guard.

At last the “heroes of the storm,” who were told they had to go out, though nothing was said about having to come back, were, for the first time, eligible for retirement pensions.