Highlights from the Great Lakes Water Level Community Workshop

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Docks continue to tower above the surface of Lake Michigan and Door County communities continue to search for funds to dredge harbors, but the state of Wisconsin wants shoreline residents to know they’re here to listen.

“We want to hear from you,” said Door County conservation officer Bill Schuster. “We want to hear what you see as problems of lower lake levels and if you have thoughts and ideas that the legislature and the agencies potentially can be doing. This is your opportunity to say that.”

Schuster was speaking at the Great Lakes Water Levels Community Workshop held at Crossroads at Big Creek on Thursday, Aug. 8. The workshop was one of four held around the state where legislators and state agency employees explained the science behind lake levels and the programs available to help communities deal with it, and to listen to public comments and questions. More than 80 people attended the Sturgeon Bay meeting.

The meeting started with an explanation of the science behind lake levels by University of Wisconsin Sea Grant coastal engineer Gene Clark. He explained how water comes into the lakes from precipitation and runoff, plus man-made diversions into the basin, and leaves through evaporation, more man-made diversions and outflow to the Atlantic Ocean. Dredging in the St. Clair River, which drains Lake Huron, also contributed to lower levels.

Clark said warming regional temperatures have led to less ice cover over the lakes, which leads to more evaporation and less water.

“It doesn’t take many degrees of warmth to make that ice layer go away,” Clark said. “Just a few degrees difference means no ice, and no ice means no evaporation, and that’s extremely important because now we’re losing that water.”

Todd Thayse, vice president of Bay Shipbuilding Company, said low water has affected the shipping industry, and so has the lack of funds available for dredging harbors and navigation channels.

“Inches certainly do matter and we’ve lost a lot of inches over the years,” Thayse said. “We can’t make it rain any more, we can’t bring any water into the Great Lakes, so from the perspective of the Great Lakes navigational community, one of the solutions is dredging.”

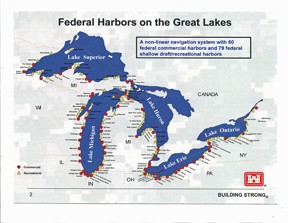

Funds for dredging and maintaining federal commercial shipping channels and harbors such as Sturgeon Bay are collected through port user fees and put in the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund. For years, a lot of that money has been diverted and not used for maintenance, even when the Army Corps of Engineers reports that 36 out of the 60 federal commercial harbors in the Great Lakes need dredging.

A bill in Congress, the Realize America’s Maritime Promise Act, would restore that fund to ensure that all the money collected for the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund actually goes to dredging and maintaining harbors. It was referred to the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure in January, and is still there.

Dredging was a big topic of conversation at the community workshop. Many people attending voiced concern about dredging practices, saying dredging seems like an expensive “band aid” solution to a larger problem.

Mike Kahr, owner of Death’s Door Marine, said dredging is important for the short term, but is a difficult job and shouldn’t be the only solution.

“The confines in what I can do and the limitations of what I have are very, very limited sometimes,” Kahr said. “You can’t wave a magic wand and get these things to happen all at once.”

Others asked the state agency representatives to look into allowing more ways to reuse dredged sediments.

There was one takeaway piece of advice from Schuster.

“Plan to be adaptive,” he said. “Certainly changes have occurred in the past and they’re going to continue to occur.”

Workshop Facts and Figures

- The Town of Baileys Harbor has dredged its marina for five consecutive years, and spent $74,451 on the last dredging project.

- Water levels are so low, ships are forced to leave as much as 15 percent of cargo behind.

- Annual recreational boating-related spending is $2 billion in Wisconsin, and supports more than 37,000 jobs and almost 800 businesses.