The Holy Grail of the Great Lakes: Le Griffon

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Many people believe Steve Libert is chasing a pipe dream by trying to place 17th century French explorer Robert de LaSalle’s Le Griffon, the Holy Grail of ships lost on the Great Lakes, in Lake Michigan.

“I get a lot of people who are brighter than me that try to tell me I’m wrong, that it’s in Lake Huron,” Libert said by telephone from his home in Charlevoix, Michigan. “They’ve pored through the documents and say there is nothing that could lead you to Lake Michigan. Well, they’re 100 percent wrong.”

Libert has had multiple translations made of the journals of Father Hennepin and Claude Bernou, LaSalle’s attorney, both of whom were on Le Griffon.

“They were describing it as they went on,” Libert said. “I know that area of Lake Michigan, and there were a couple of passages where I said, this is not Lake Huron. This is Lake Michigan.”

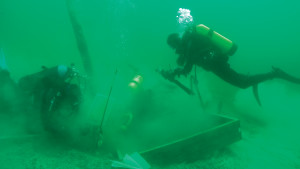

While Libert and his team, the Great Lakes Exploration Group, Inc., have been diving the area (which we will not disclose) for decades, going back to 1980-81, it was 13 years ago that Libert and the team found a 20-foot piece of wood speared into the bottom of Lake Michigan, six miles off what is known today as Michigan’s Garden Peninsula.

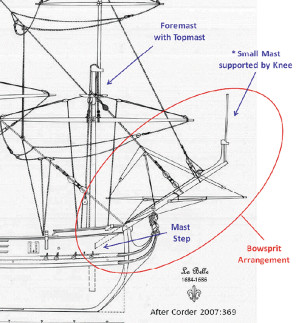

“I’ve always said it was a bowsprit or some type of mast,” Libert said.

Libert suspects it is a piece of Le Griffon, a 45-ton barque that the indefatigable explorer de LaSalle had built in 1678 on the upper Niagara near Fort Frontenac (modern-day Kingston, Ontario) for his westward voyage on the uncharted Great Lakes, in search of that elusive Northwest Passage to the riches of the Orient.

Submitted photo.

Naysayers identify the old wood Libert found stuck in the bottom of Lake Michigan as a stake for a pound net, an intricate net-fishing system requiring stakes driven into the bottom of the lake and used on the Great Lakes.

Tests to determine its age have been inconclusive, but several Carbon-14 dating tests puts the chunk of wood in the range of 1670 to 1950.

While not conclusive, the results give Libert reason to continue the search in the area that has captured his attention. Had the earliest date been any later, it would have completely ruled out his theory. And Libert scoffs at the pound net stake idea.

“I’ve seen many of them in the water and on land, but I’m not an expert,” he said. “We did have an expert on board, Charlie Henriksen, and he’s right there on the Door. He is a commercial fisherman who has used pound net stakes before.”

Henriksen has been part of the search for nearly three decades.

“We’re definitely onto something,” he said. “Every time we go, there’s just a little more evidence.”

Carl Carlson of Ellison Bay has been another longtime member of the team, and it was he who got Charlie involved.

“It kind of fell in my lap because of my good friend, Carl Carlson,” Henriksen said. “Carl has been diving with Jim [Kucharsky, one of Libert’s partners in the LaSalle-Griffon Project] probably 35, 40 years. I got involved because Carl asked me to haul some equipment up for them and help set up their camp on Poverty Island.

“I’m fortunate to be a part of it. The twists and turns it’s taken in the darn near 30 years we’ve been going up there is pretty amazing,” Henriksen continued. “I’ve always been fascinated by the history of exploration, of all kinds, Lewis & Clark, the Griffon, the Kon-Tiki. Things like that have always fascinated me and the whole spread of civilization and what people did to discover this country. It’s pretty amazing. Just the sheer bravado it took.”

Henriksen said proof of how strong the evidence is can be seen in his son, Will, who has signed on for the next search for evidence.

“If this trip goes the way they are hoping it goes,” Henriksen said, “he might miss the Packers home opener, and Will is a diehard. But he said, ‘Well, if we’re not back, we’re not back.’ That’s kind of how I gauge his interest.”

Henriksen’s interest in being a part of lifting the veil on one of the Great Lake’s great mysteries is palpable. “We may never know the whole story,” he said, “but it is certainly fascinating to have a chance to participate in the search.”

This is not a treasure hunt.

“We’ve been called treasure hunters,” Libert said. “If that were true, I wouldn’t be up in Lake Michigan. I’d be off the Gold Coast, the Florida Coast, not up in the cold water of Lake Michigan. I wouldn’t do it if I didn’t think this was the Griffon.”

When Libert talks about the search for Le Griffon being a life quest, he is not kidding.

“A lot of people don’t believe it, but this has been with me a long time,” he said. “I just returned from Dayton, Ohio, where I went to school. It was my wife’s 40th high school reunion. We were high school sweethearts, but I was a year ahead of her. There were a couple people there who remembered because they were there.”

He refers to the moment when finding Le Griffon became a personal challenge.

“It was my eighth grade history teacher, Mr. Kelly,” Libert said. “This is going back to 1968. Mr. Kelly was discussing early explorations by Europeans. He talked about LaSalle and the ship Griffon. He described the figurehead, which is part lion and part bird. And then as he’s walking around the room talking, I’m sitting by the window and I’m looking out the window, but I am listening to everything he’s saying. He walks right up to me and puts his hand on my shoulder. I thought I was going to be in trouble because he thought I wasn’t paying attention. But he goes, ‘Who knows? Maybe someone in this room will find the Griffon one day.’ That really sparked the interest.”

Libert was a high school football star who earned a spot on the Ohio State squad under the legendary Woody Hayes, which kept him occupied on matters other than a 300-year-old vessel.

“After I left Ohio State, I still kept thinking about LaSalle and the ship. I want to go look for that vessel,” he said. “So I learned how to dive. Did a lot of research. Darned if I didn’t bump into something in 2001 after 20-some years of diving and research.”

That’s the 20-foot chunk of wood he and his team found. About 11 feet of the thing was visible, and another nine feet had to be dug out of the sediment.

“One of the major stumbling blocks was the litigation we had with the state of Michigan over this shipwreck,” Libert said. “The state tried to claim everything on the bottom of the lake belonged to them. They told us, ‘You might as well tell us where it is because we own it.’ There were different groups trying to take our discovery over, state and federal departments. We ended up in federal court and it took almost 12 years in  order to get the permits just to do a test excavation.”

order to get the permits just to do a test excavation.”

Lengthy legal battles followed between Libert, the state of Michigan, the U.S. government and the government of France about ownership of the find. France claimed that if Le Griffon is found, it will belong to them because King Louis XIV financed LaSalle’s explorations. In July 2010, the Great Lakes Exploration Group, the state of Michigan and France reached agreement to cooperate in the next phase of an archaeological assessment for identifying the shipwreck. At the time, Libert stated that “if the Le Griffon is found, hopefully France will give us a 99-year lease and that we will be able to go ahead and offer our opinion on what to do with it.”

Subsequent searches, including a 2013 session with three French underwater archeologists, led Libert to believe they have more evidence of Le Griffon 118 feet southwest of where the 20-foot piece of wood was found 13 years ago.

“We decided to go back in June,” he said. “We started searching where I wanted to search to the southwest, 118 feet exactly right from the bowsprit. We started finding timbers with very old fastening devices, I’m talking tree nails (wooden dowels or pegs used in shipbuilding), some wrought iron nails and something like a concave washer that was used in shipbuilding, especially by the French. So we were pretty excited about that. The fastening devices look like they could be from a very old vessel. We know that because they match with the LaBelle [LaBelle was another ill-fated LaSalle ship that went down in a storm in the Gulf of Mexico’s Matagorda Bay off the coast of Texas in 1686 and was discovered in 1995; it is considered one of the most important shipwrecks ever discovered in North America]. Those fittings look exactly like what we saw. So, the French are pretty excited right now. So are we.”

Libert said he and his team have known the location of what they believe to be the hull of Le Griffon since 2006.

“We are sure we know where the hull section is,” he said. “What we know for sure is that we have a ship that’s extremely old. If it’s 300 years old, there’s only one ship it can be that’s been documented on the Great Lakes. Somebody said, ‘How do you know it’s not a Viking ship?’ You know, I would love to find a Viking ship, but I can tell it’s not a Viking ship just by looking at it. We just know it’s very old and it fits right into the research I have. It was described very well by Father Hennepin and Bernou.”

Besides the exploratory visit to the search site this fall, Libert said he is planning a return in June 2015, probably with the French archaeologists. He added that Washington Island may figure into that session.

“There was the biggest argument, did it make it to Washington Island? From primary source documents, it was very easy to figure out where in Washington Island the ship put in, just from the description,” Libert said. “Washington Island is definitely involved. I’d like to get my guys back in there. There are a couple of things I’m still looking for. Who knows, they could still be there. Maybe not. If the French have enough time and this is the Griffon, you may be seeing the French coming to Washington Island. I’m really looking for good things to happen next year. Or even this year.”

And even if he does have to hand over his find to the French, there will be personal vindication for Libert and his team.

“I get a lot of calls and emails, and there are a lot of blogs, people trying to discredit us,” he said. “I think we’ll have the last word on that.”

Not the First to Find Le Griffon

Steve Libert is not the first person to believe he has found Le Griffon.

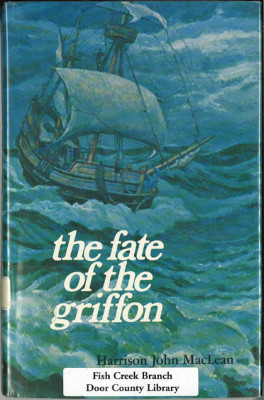

In 1974, a book was published by Canadian newspaper reporter Harrison John MacLean called The Fate of The Griffon (available at the Fish Creek Library). MacLean claimed that a Canadian commercial fisherman on the Bruce Peninsula on Lake Huron had found the wreckage of Le Griffon, and that the fisherman’s family had known about the wreckage for 120 years.

MacLean spent 19 years researching LaSalle’s voyage and Le Griffon before the book was published in ’74, but subsequent independent research of the wreck in 1980 determined that it was a Mackinaw boat used in the fur trade circa the 1850s.