Housing and Economic Development Are Intertwined

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

by Jim Schuessler, Executive Director, DCEDC

The recently completed Door County Housing Analysis indicated the need for hundreds of units of attainably priced apartments, senior housing and seasonal housing, and Door County Economic Development Corporation (DCEDC) is working to solve this housing crisis. We cannot solve this problem on our own, so DCEDC is working with county and local government officials and their staff members.

Over the past decade, the housing-affordability crisis has worsened in many places. Young professionals and working families are having an increasingly hard time finding affordable housing, particularly in communities that are well connected to employment options, transportation and other services and amenities. Retiring baby boomers are also moving from owned homes to rented apartments.

Rising housing costs, insufficient new residential construction and stagnant or slow-growing wages have led to a situation in which teachers, engineers, police officers and nurses – as well as workers in retail, restaurant, creative-industry and entry-level technology settings – are forced to commute long distances to find affordable housing or share housing to reduce costs. Often they must leave for “greener pastures” or pass on a Door County opportunity altogether.

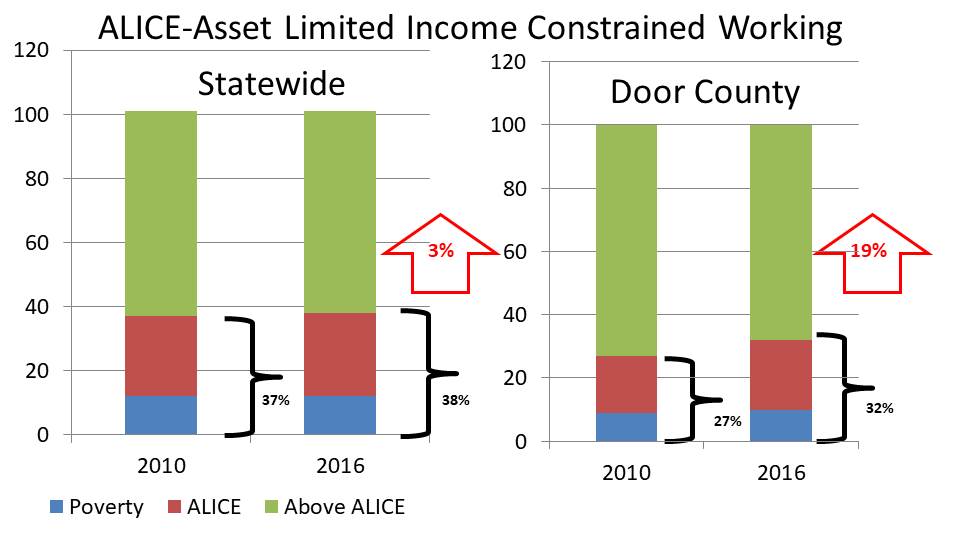

In the county, we have a growing group called ALICE (Asset Limited Income Constrained Working) that is being squeezed out of the local economy. According to the United Way, Door County’s numbers grew an astounding 19 percent over a six-year period, and this indicates that we are headed in the wrong direction.

When the local workforce can’t find affordable housing, the entire community suffers. Research has well established that having access to affordable and stable housing in good neighborhoods is associated with positive health, education and economic outcomes, but having a sufficient supply of housing that is affordable to households all along the income spectrum is also critical to supporting vibrant and sustainable local economies.

There are several ways to think about how housing availability and affordability relate to a community’s economic health and prosperity. Lower-wage workers are among the first to feel the pressure from higher rents and home prices if there is an insufficient supply of affordable housing. This can include workers in the retail and restaurant sector, the travel and tourism industry, and in many critical, community-serving occupations such as child-care workers, nursing assistants and home-health aides. In Door County, for example, wages have not really budged in the past decade for adults aged 25 to 34. This often means that wages are insufficient to pay the county’s typical rent or purchase an average-priced home.

Even if workers do not leave the community, the lack of affordable housing still has implications for the local economy: As workers must spend more on housing, they spend less on locally based goods and services, so the county’s economy is less able to support diverse retail, restaurant, recreation and other amenity options.

As the Amazon HQ2 process illuminated, businesses are increasingly looking at quality of life, economic diversity and cultural tolerance as they seek to locate or expand. Key components of that quality of life are housing availability and affordability for workers from the CEO to the line worker or entry-level salesperson.

This link is increasingly evident in Door County as employers engage in a worldwide battle for talent. In more affordable counties, there is an opportunity to get ahead of the curve: to sustain a high quality of life and a low cost of living that create a comparative economic advantage.

There are strategies to develop a sufficient supply of housing to meet a community’s workforce-housing needs. Some are limited by state statutory authority, but a range of tools is often necessary to develop the right kinds of housing.

Door County is likely suffering from this crisis more than many other areas because of our high demand for vacation rentals, so a pilot project to allow development incentives, including with local townships, would be helpful. Zoning changes to allow smaller homes on smaller lots is a critical tool for promoting attainable housing options. Research shows that millennials want more experiences and less “stuff.” Using publicly owned land and public-private partnerships are increasingly important in building affordable housing. Finally, regulatory approaches, including inclusionary zoning, can be part of a county’s housing toolbox.

But beyond tools, an essential step – for DCEDC, citizens, business owners, community groups such as the Interfaith Prosperity Coalition and elected officials – is to work collaboratively to solve our housing crisis. Supporting housing for our workforce is good for our residents, our communities and our sustainability.