Photo Essay: A Story of Ice

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

With a few rare exceptions, Lake Michigan’s Green Bay freezes over every winter, usually for eight to 12 weeks or more. It’s one of only a handful of places on the Great Lakes where this happens on a regular basis.

Depending on the speed and severity of the freeze, ice can form to a thickness in excess of three to six feet on the bay, making the 1,600-square-mile expanse of water look more like the North Pole than the great inland sea that we all know and love during the summer months.

Over the years, I’ve looked out across our small slice of the cryosphere and found little of photographic interest, other than the crisp, minimalist line of the horizon. I didn’t grow up on the bay, so I never thought much of venturing out onto it during the winter. Yet that is what many have done, from the earliest settlers taking goods to market, to entrepreneurs moving entire hotels across the ice, to today’s weekend warriors zooming over it on snowmobiles and fishing through it in heated shanties.

Sunset over Green Bay near Ellison Bluff County Park. Photo by Brett Kosmider.

Photo by Brett Kosmider.

My first foray over the ice was actually by air, with a drone. It wasn’t until I trained my camera straight down did my interest in lake ice consume me.

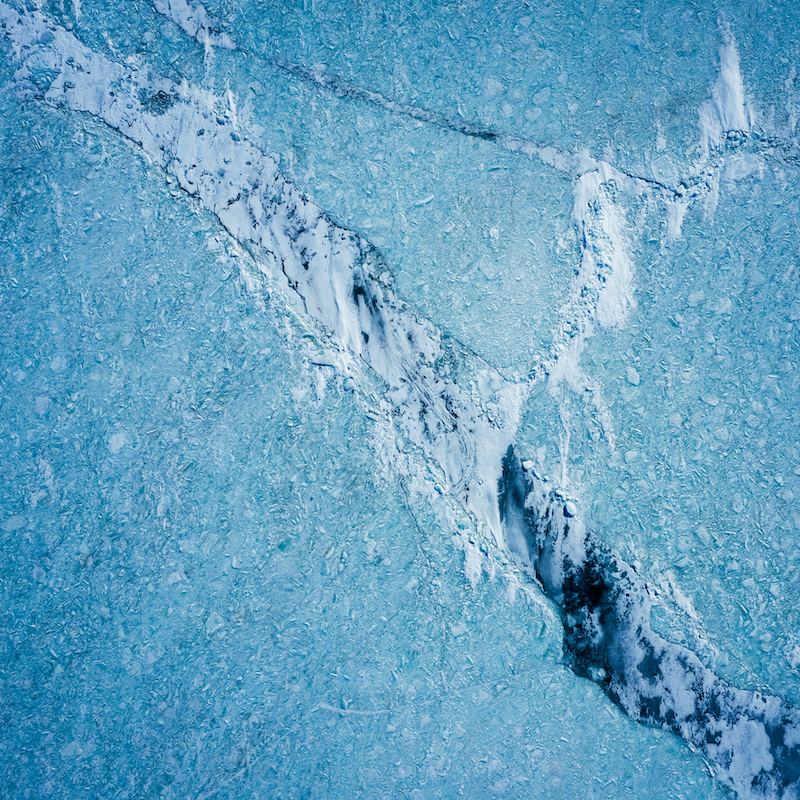

Here is a world that few have had the chance to see: a dynamic world that varies day by day, from one location to the next, as the ice continuously evolves in shape, color and texture. There’s gray ice, white ice and black ice. Ice feet, ice rind and pack ice. Like the Inuit language possessing many words to describe snow, so there are many terms to describe ice on the Great Lakes. Each relates how the ice was formed or the state it’s in.

Typically, ice begins to form in smaller inlets and bays, usually in mid- to late December, when the water near the surface is cooled by subfreezing air with little or no wind and few, if any, waves. This sheet can quickly extend out from the shore, but it also freezes down into the depths of the lake.

During a series of very cold, still nights, the entire bay freezes over. Some of the more visually interesting ice formations are created by the churning up and refreezing of sheets of primary and secondary ice into a fruitcake-like amalgamation called agglomerate ice.

Scientists are studying the effects of lake ice on local weather patterns courtesy of records that have been kept over the past five decades. They’re finding that without lake ice, Great Lakes communities bear the brunt of larger snow events, and the basin as a whole is facing decreasing Great Lakes water levels through increased evaporation.

Photo by Brett Kosmider

Little Harbor, Sturgeon Bay. Photo by Brett Kosmider

Sure, we’re coming off historically high water levels, but the trend of a warming climate and warming waters in the lakes sets the stage for long-term losses in Great Lakes water levels: something that will affect everyone from local merchants, fishers and resort owners to large manufacturers in distant cities that rely on the Great Lakes to engage in commerce.

I’ll always look at the bay differently now during the winter months: as a constantly evolving visual playground full of drama and conflict, with opposing natural forces creating an infinite palette of wonder that I can return to on a daily basis to find inspiration.

But I’ll also look at the bay and its ice as reminders of my duty to my friends and neighbors — whose livelihood depends on that sweetwater miracle that is literally outside our doorsteps — to do whatever I can to preserve it. My muse is a complicated beast: one full of power and might, but also surprise, beauty and delicacy. My muse is the water all around us: life giving, sustaining and worth protecting for all.