Icelandic Emigration to Washington Island

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

In his role as a bookseller, my father was often asked to give talks about Door County books and authors to various groups and organizations. In those days, most Door County literature was either memoir or history, so my father often began his talks with: “Never has so much been written about a place where so little of significance has ever happened.”

While I generally agreed with my father’s assessment, I was quick to point out that this did not mean that nothing of significance had ever occurred on or around the Door Peninsula. I noted Death’s Door Passage and the many shipwrecks and I also stressed the significance of Washington Island’s Icelandic settlement. And while almost every visitor is intrigued by Death’s Door and shipwrecks, very few appreciate the island’s Icelandic influence.

In the mid-1800s, Iceland was mired in the same economic difficulties that beset most of Europe. Adding to the difficulties was overpopulation on the island in relation to the available resources. This left many young people with the difficult prospect of moving inland where scarce topsoil made farming a difficult, if not an impossible proposition.

The country was under the control of Denmark and though an independence movement was starting to take hold, many Icelanders decided to leave their home for other parts of the world. Between 1870 and 1900, 15,000 Icelanders emigrated: 20 percent of the country’s population.

The first group of Icelanders to emigrate in the United States arrived in 1855, lured by Mormon missionaries to settle in Spanish Fork (still in existence today), but the resettlement to North America really began to take hold beginning in 1870.

The story of Washington Island’s Icelandic settlement (which most feel is the second oldest settlement in America, after the Utah settlement) begins in 1870. At that time, 5,212 Danes were living in Wisconsin and 49 of these were living on Washington Island. Among the Danes in Wisconsin was William Wickman, who, though born in Denmark, had worked for a time in Eyrarbakki on the south coast of I celand before immigrating to Milwaukee in 1865.

celand before immigrating to Milwaukee in 1865.

Wickman regularly corresponded with his former employer in Eyrarbakki, Gudmundur Thorgrimsen, a merchant of considerable influence. This correspondence, particularly Wickman’s often glowing praise of America and Wisconsin in particular, led Thorgrimsen to share the praise with customers in his store.

The first to heed Wickman via Thorgrimsen was 20-year-old Jon Gislason, who worked in Thorgrimsen’s store. With the blessing of his employer and a sizeable inheritance from his father, Gislason began planning a trip for the spring of 1870.

Soon joining Gislason was 24-year-old Arni Gudmundsen, a carpenter who also did work for Thorgrimsen, and Jon Einarsson. While Gislason provided financial assistance to these two men, the fourth man to join, Gudmundur Gudmundsson, was a financially successful fisherman and was able to pay his own way (at 27 years of age, he was also the oldest of the four).

It is interesting that most sources refer to these four men as “the four bachelors,” and while the sources don’t explain this appellation, it can be reasonably presumed that it was important to them to identify themselves as single, unattached men in order to dispel any notion that they had abandoned families back in Iceland.

The four left Eyrarbakki on May 12, 1870, and travelled by road the 50 miles to Reykjavik. From there, as Washington Island historian Conan Eaton wrote, their “route led by post ship via the Faroe and Shetland Islands to Copenhagen; by steamship to Hull in England; by train to Liverpool; across a turbulent Atlantic to Quebec … by eight days’ halting train travel to Milwaukee, which they reached on June twenty-seventh.” It was in Milwaukee where they met up with Wickman, who helped them find work.

In the fall, the four Icelanders and Wickman arrived on Washington Island via a Goodrich steamer, where they began work cutting trees – a profession they had little familiarity with since Iceland is virtually treeless. Still, the residents of Washington Island were welcoming and patiently tutored the four in the art of lumbering.

Not long after their arrival, Wickman and Gislason purchased a wooded 61-acre homestead with 1,500 feet of frontage on Detroit Harbor. This homestead would form the nucleus of the Icelandic community.

Though the work was hard, the four Icelanders managed to acquit themselves well in their new community and, most importantly, sent letters home that, while not omitting the hardships, reported favorably on their new circumstance.

The earliest letter that survives dates from March 8, 1872, and, though the author is unknown, the presumption is that it was either Jon Gislason or Gudmundur Gudmundsson. The letter was reprinted in its entirety in Nordanfari, a local newspaper in the town of Akureyri, and it says, in part:

“This place [Washington Island] is one of the best for poor people to come to, for here they can live off the water and off the land … I dare say there is no lazy and idle man in Iceland that I know, no matter how many children he has got, who cannot live a good life here. Even if the man would be too lazy to do anything, the wife would be able to grow enough in front of the house to live off, but I expect the man to fish in the lake, because there is quite enough fish close to shore, which is good for eating.”

Not surprisingly, given the positive reports in these letters home, more Icelanders followed. A few arrived on the island in 1871, including Einar Bjarnason who arrived with two of his children (his wife and eight additional children followed two years later). By late August 1871, the Door County Advocate reported, “A number of Icelanders are expected at Washington Island this fall to make that place their future home. Quite a colony is expected.”

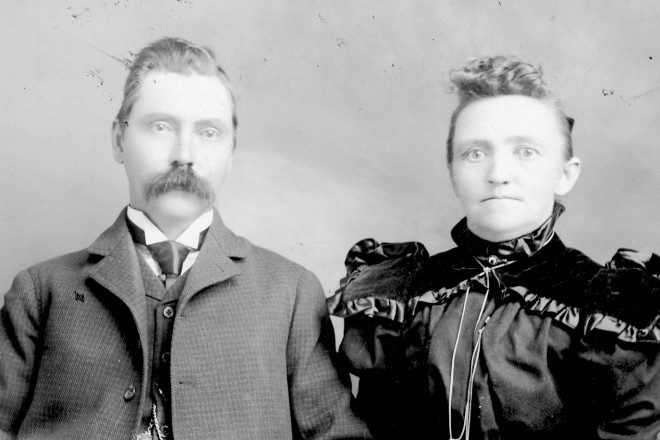

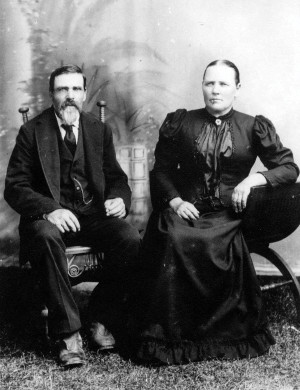

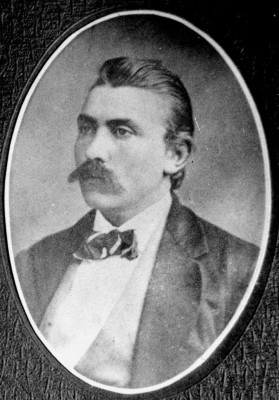

Photo courtesy of Washington Island Historical Archives.

Another 20 Icelanders arrived in 1872 and modest numbers continued to arrive in the ensuing years. By 1885 the number of Icelanders on the island numbered about 70 and, while printed stories in the late 1900s tended to exaggerate the Icelandic population, the number of adult males who settled permanently on the island by the end of the century numbered approximately 20. When women and children are counted this number was slightly more than 100.

Gradually, the immigrants began to integrate themselves into island life. Most significantly, in 1885 Arni Gudmundsen convinced his younger brother Thordur to come to the island to practice medicine. As the lone doctor in the isolated community, Thordur’s contributions to the community were immeasurable and led to the widespread acceptance of the Icelandic population as an integral part of the community.

Descendants of these first Icelandic immigrants still reside on the island and their heritage is honored at numerous sites and namings (Washington Island Ferry Lines ferry “Eyrarbakki,” for example) throughout the township.

Today, there are between 40,000 and 45,000 Icelandic Americans living in the United States. And because this number is so small (as were the total number of immigrants between 1855 and 1910), the Icelandic settlement on Washington Island, though modest, remains a very significant part of Door County’s, Wisconsin’s, and America’s history.

Sources:

Michigan History, Volume 66, Number 3, May/June 1982, “From Eyrrbakki to Muskegon: An Icelandic Saga, letter edited by Conan Bryant Eaton, pages 13 – 15.

Washington Island 1836 – 1876, A Part of the History of Washington Township, by Conan Bryant Eaton, revised edition 1980.

History of Door County, Wisconsin: The County Beautiful, Vol. 1, by Hjalmar R. Holand, Wm Caxton Ltd © 1993

Discovering Door County’s Past, Vol. 1, From the Beginning to 1930, by M. Marvin Lotz, Holly House Press, © 1994

Let’s Talk About Washington Island, 1850 – 1950, by Anne T. Whitney. 1995 edition

Special thanks to Janet Berggren, Archivist at The Washington Island Historical Archives, Washington Island, Wisconsin.