Ingert & Al

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

I call Al and Ingert at home to set up an interview. Al answers, saying simply, “Al Johnson” – as always, no “hello,” nothing at all prefacing his name, his tone making you wonder if you’ve somehow already irritated him. (Which, maybe, you have: he doesn’t like interruptions and he prefers dealing with people face-to-face – he really dislikes cell phones, e-mail, and answering machines. I personally suspect his favorite thing about telephones is hanging up when he is done with the conversation – although you may still be talking – his customary closing, if you get one, being a loud “yeah, good-bye.”)

Al says Ingert won’t do an interview – she “doesn’t like that kind of thing” – but he’ll talk to me “in a few days” (he’s been saying this for weeks). Then I hear Ingert in the background, her voice still characterized by a thick Swedish accent even after decades of living in the United States, asking, “Is that Mariah? Let me talk to her. I have some ideas for articles.” We proceed to talk for an hour, starting with her article ideas – local people she thinks more interesting than she and Al, and the fact that Sister Bay in particular and Door County in general have turned into places inhabited primarily by retirees rather than working residents and young families – but easily shifting to the article I am in fact writing.

Born in Sweden in the small village of ضsterbymo, Ingert came to the United States in the late 1950s for a one-year visit. She was 17; she knew no one, had no job, and had only $100. She didn’t like her first job – babysitting for a family on the south side of Chicago for 18 dollars a week – but quickly found waitressing jobs first at a small restaurant, then the Swedish Club, then Tam O’Shanter’s. She liked the U.S. so much she stayed two years before returning to Sweden for even a visit.

While living in Chicago, Ingert visited Door County with artist friend and roommate Malin Ekman. (Malin – whom Ingert and others who knew her in her teens and 20s call “Marlene,” but who most people call by her childhood nickname, “Tudy” – now lives in Baileys Harbor.) Ingert decided to move here in 1959, saying, “It was kind of fun – I didn’t know anything about Door County other than from visits with Marlene and her parents. I saw the Gordon Lodge ‘Help Wanted’ ad in the Chicago Tribune and called. They told me to come on up, so I did. I had no radio, no TV, no telephone, no nothing. I thought it was heaven, especially since people on vacation were much nicer than in the city.”

Ingert remembers meeting Al in 1958 during one of her visits with Marlene. She says, “I saw him up at the Sister Bay Bowl. He chased me and chased me and chased me. I didn’t want to go out with him.” Eventually, she gave up; they married in 1959.

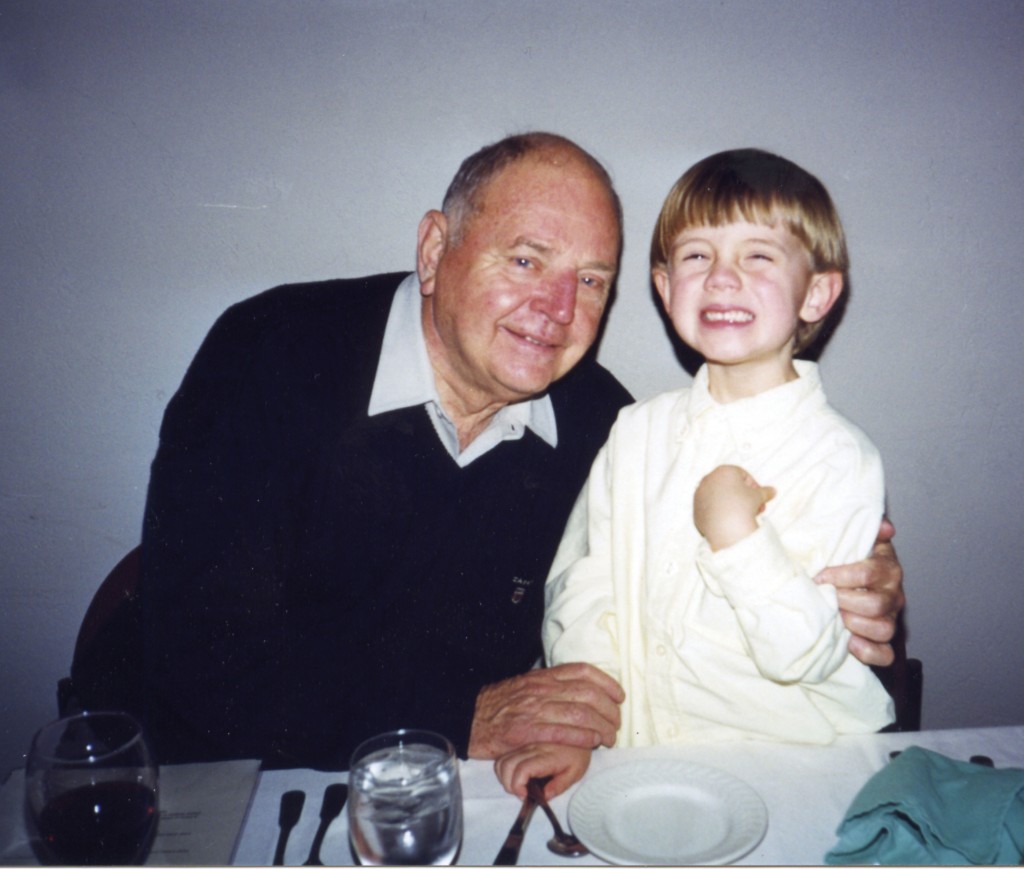

When I sit down with Al a week after my conversation with Ingert, he says Ingert is correct – he really had to convince her to date him. According to Al, however, they met in 1959 and married in 1960. At any rate, they did get married, had three children – Lars, Annika, and Rolf – and then two foster children, John and Dennis. Between their five children, they now have ten grandchildren.

Al had been living in Door County full time since 1947 and had started the now-famous Al Johnson’s restaurant in 1949. After serving in World War II from 1943 to 1945 in the 101st Airborne, he had subsequently graduated from Marquette University with degrees in criminology and psychology.

Al was born in 1925 on the south side of Chicago to first-generation Swedish immigrants. He barely mentions Chicago when talking about his childhood, instead immediately talking about Door County. He remembers, “The first time I was up here was when I was a little kid. I spent most of my childhood up here. My parents sent my sister and me up here every summer to get us off the streets of Chicago. I spent every summer in Door County ‘til the war.” He also notes, “I went to Sweden with my sister Millie when I was six years old to live for two years with my mother’s parents, in Vännäs.”

When he and Millie were in Door County, they stayed with families his parents knew from their vacations in the Sister Bay area. One family, the Larsons, had a grandson – Winky – with whom Al became fast friends. It was Winky who years later gave Al the birthday gift of a goat to put on the sod roof of the restaurant, marching the bow-decorated creature into a dining room full of customers.

When asked about community involvements, Ingert first says she’s done “nothing.” Then she remembers she headed the local Cub Scouts for seven years. And, “oh yes, worked also with beautification – I wanted the billboards down! And we did it, we got the Sister Bay billboards down.” She also off-handedly mentions that they had “34 kids in our house, over 34 years. Anytime someone came to work at the restaurant and had no place to live, I gave them a place to live.”

Al served on the Sister Bay Village Board in the 1950s, the Gibraltar School Board for 17 years in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and the county police commission. He laughs, saying, “I’ll tell you a little story about when I was on the village board. I made a motion to buy Mrs. Lamb’s property – the Helm’s property the village just bought for $4.8 million. It was for sale for $35,000. The motion was defeated 4-2.” The biggest challenge the village faced during his tenure, he says, “was over the issue of putting sewer and water in at the same time. When people complained we couldn’t afford to put in water, too, I said we couldn’t afford not to! We were right, too – look at the water quality issues other communities up here have had. When customers in the restaurant ask me if our water is safe to drink I pick up their glass and drink from it.”

Neither Al nor Ingert mention that they and their children – all of whom have at one time or still do work at the restaurant – have contributed to the community through the restaurant itself, although they frequently provide non-profit donations and event sponsorships. Al does note he has probably employed more than 2,000 people over the years, proudly pointing out that many worked at the restaurant for many years and/or “put themselves through school working here,” nodding my way as he remembers both statements to be true for me. (The longest tenured employee was June Kwaterski: she started waitressing for Al in 1949 when the restaurant opened and faithfully worked there in one capacity or another until she died a few years ago.)

Many locals and regulars would consider the “coffee table” one of the restaurant’s major contributions to the community. A large table in the back where people – mostly men, until recent years – gather before the breakfast rush and after the lunch and dinner rushes, it is probably the place to find out what people are doing, thinking, and talking about in Northern Door. Al recalls, “When my father-in-law came over here visiting from Sweden, he thought it was unbelievable and remarkable you could have a doctor, a lawyer, a banker, a teacher, an owner of a company, a carpenter, and a plumber all sitting at the same table. That wouldn’t have happened in Europe – at least not at that time – they were very class conscious.” Al is also proud that while discussions are frequently lively and heated all part and consider themselves as friends (Al has always been a staunch Democrat, but many coffee table regulars are Republicans).

Al doesn’t get excited talking about celebrities that have eaten in the restaurant over the years, preferring instead to talk about politicians. He proudly notes, “One time, we had four different governors from four different states in here – Illinois, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Indiana – eating at four different tables at the same time.” As to his current political concerns, he says, “The biggest thing right now is the election coming up. We’ve got to have a change of direction. We’re going the wrong way. There used to be a time when you came from America and you would to go Europe and they really respected you. Now, more people despise us than in any other given time. The one thing we haven’t learned is you can’t tell people how to live their lives. You just can’t tell other people how to live, in other countries or at home.”

Fairness and responsibility – for our own actions, for individuals we come across in our lives, and for our broader community – are key values to Al and Ingert. Indeed, neither have ever been afraid to take on duties assigned to employees. Waitresses scatter when they see Ingert coming, afraid of what cleaning chore she might undertake and who she might enlist to help. Well into his 70s, Al raced around the restaurant clearing tables and pouring water and coffee for customers and, his favorite, relieving the dishwashers, convinced he did dishes faster and better than anyone else. On rare occasions when waitresses were completely swamped, he started taking orders and serving tables. (He never wrote anything down, claiming a perfect memory. I suspect customers just meekly ate whatever he put before them.)

Even now, Al or Ingert are frequently out in front of the restaurant and gift shops sweeping, weeding, picking up garbage, hosing off sidewalks, and watering plants, and Al frequently still does the restaurant register evening close-out. Ingert laughs that she has always been largely behind the scenes, so “people don’t know who I am – they ask me all the time if Al is still living. Everyone always thought June was Al’s wife because she had worked there for so long and because people always saw her there. When they ask me that, I usually tell them he seemed okay at breakfast!”