Island Incubator Withers

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

It’s not often that a developer takes hundreds of thousands of dollars across Death’s Door with a proposal to invest it in a multi-faceted business development in the middle of Washington Island.

So when Chicago architect and island property owner Scott Sonoc presented a plan to rehab the old cheese factory on the corner of Range Line and Town Line Roads and build a business incubator that would house a commercial kitchen and several spaces for other start-ups, the proposal excited many islanders. But now Sonoc’s project has stalled, and he blames the Door County Planning Department for placing too many hurdles and conditions in the way of the project.

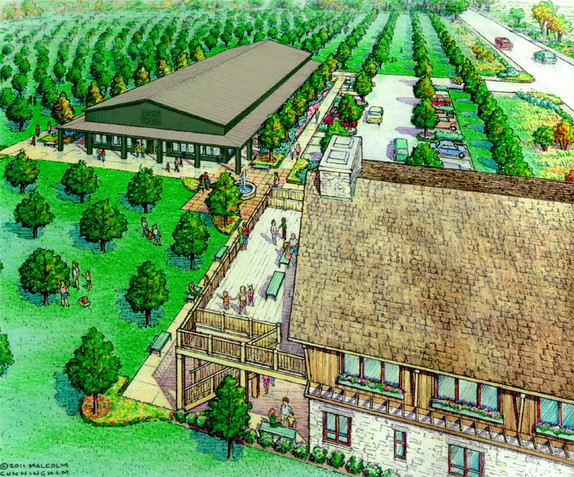

An artists rendering of Scott Sonoc’s business incubator and chalet project located at the old cheese factory (in foreground). Sonoc said county zoning regulations killed the project.

To proceed, Sonoc must get the property rezoned from General Agriculture to Mixed Use Commercial and obtain a variance from county setback requirements to rebuild a deck that collapsed decades ago. He also must obtain conditional use permits for the different businesses that could be located in the incubator.

Sonoc said the cost of the permits, the lengthy review process required to obtain them, and the cost of fees for lawyers and architects to pursue them, made it impossible for him to move forward. In a Dec. 4 statement announcing the cancellation of the project, Sonoc said Door County government staff “have created a business climate that is unstable and that actively discourages investment.”

“A huge amount of time and money gets wasted,” Sonoc said, and he contends that if a zoning administrator makes a mistake, it is far too costly and time-consuming to challenge that mistake.

County officials, however, say the variance fees and permits don’t even cover the expense of reviewing applications and making site visits. Further, they point out that the process required to obtain them is determined by the state, not the planning department. In fact, county officials say they have bent over backward for Sonoc.

“We have presented several options for ways he can get the project approved,” said Kay Miller, the zoning administrator who oversees Washington Island.

Sonoc and his supporters, which include Town Chairman and County Board Supervisor Joel Gunnlaugsson as well as Dick Purinton, CEO of the Washington Island Ferry Line, argue that the planning department should do more to help Sonoc and other developers move forward.

“I can’t see anyone else taking something like that on,” Purinton said. “His incubator proposal seems to fit the island community and economy as well as any idea to date. This should be a project that should be approached with an attitude to help make it happen. Maybe the planning department staff has done all they can in terms of the letter of the law, but maybe there needs to be a re-examination of the way they operate to make something work.”

But Door County Planning Department Director Mariah Goode said she and her staff don’t have a lot of latitude for interpretation of state statutes and ordinances.

“For good or bad, there are definitive rules,” Goode explained. “We have been hired to administer the rules, and it’s not fair to our staff to jump up and down in anger when we administer them. We can’t just not administer rules and follow the processes in some cases. If someone doesn’t like the rules, then let’s look at changing the rule, not get upset with the people administering the ones we’ve chosen.”

Sonoc believes the zoning code does leave room for interpretation, however, and argues that there should be a simple, cheap process to crosscheck decisions.

Gunnlaugsson proposed that the county eliminate fees for variances and site visits (which are rarely charged, Goode said), but his proposal went nowhere.

“I understand the county’s position that it costs money to deal with an appeal, but I believe that that cost should just be on the tax roll,” he said. “I think it’s part of the job and the process.”

Two other developers who have completed many projects throughout Door County said the variance fees have never been a hindrance to a project. Sonoc said his frustrations aren’t solely related to the fees.

“I’m standing on principle,” he said. “The variance requirement kicks open a process where you must submit drawings, bring in a surveyor, submit it to the town plan committee, then the town board, then to the county board. It can take three months to get to the Board of Adjustment. If they deny the application, then your only recourse is to go to Circuit Court, so you have to have a lawyer and architect with you at the review, because if you’re not prepared you’re going to have to go to court.”

Goode downplayed that notion, saying that very few people bring a lawyer to Board of Adjustment hearings and that nearly 80 percent of variance applications are granted, and she said there’s little possibility that Sonoc’s would not be.

“What he’s asking for is pretty innocuous,” Goode said. “I can’t see how it wouldn’t get approved.”

Essentially it requires going through the motions, and though Sonoc’s backers would prefer that step be eliminated, the planning department and county board doesn’t have the authority to do so. State statutes require a permit for projects that don’t conform to established zoning, and statutes also mandate that the public be given a chance to comment and that proper notice of a hearing be posted.

Door County went beyond state requirements by giving the towns, at their request, the option to review projects and make a recommendation to the county’s Resource Planning Committee. Goode said that’s the only step the county could eliminate, “but I don’t envision the towns wanting to give up that option.”

“It’s more cumbersome,” said Door County Administrator Mike Serpe, “but it’s probably healthy. The towns want to have their say. The rules are there because the people of Door County have decided that that’s what they want.”

Purinton – who has reviewed the trail of correspondence between Sonoc and the planning department – said the county should do more to move projects like Sonoc’s along.

“I do feel that there was an inability on the part of the county to cut through the impasse and find a path to move forward,” Purinton said. “It seemed as though there was some entrenchment on the part of the planning department.”

“Door County is more difficult to do a development in than any place I’ve worked,” Sonoc said. “In other places they ask ‘What can we do for you?’”

Goode said it’s inappropriate to label her department as discouragers of business or development. Planning Department staff members, she said, do their best to facilitate projects and have proposed changes to county zoning to streamline processes for various uses. “We are, however, legally bound by the ordinances the county has adopted and, often, by state statutes.”