It’s Tick Season, and They Really Bite

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Last spring, “Corona and Lyme” would have sounded pretty good to many people, but now it’s probably the last thing most want to hear about. However, as many people are spending time outdoors and exploring nature without the fear of contracting COVID-19, there’s another serious disease they should be concerned about contracting.

Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium spread to humans through the bite of an infected deer tick, also known as the black-legged tick. Other types of ticks are found in Wisconsin, but it’s the deer tick that spreads the disease in the northeastern, mid-Atlantic and north-central United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Ticks tend to live in shady, leafy, wooded areas or areas with tall grass, and they usually stay close to the ground, crawling aboard people and animals when the host brushes against the tick’s habitat of leaves or grass. Ticks are most active from May to September, particularly when the weather is warm and wet.

A fever, sweats, chills, headache, fatigue, stiff neck, muscle or joint pain, and a circular, reddish rash are early symptoms of Lyme disease. If left untreated – oral antibiotics are most commonly used, and no human vaccine is available – Lyme disease can cause arthritis, meningitis, facial palsy, heart abnormalities, nerve pain and numbness or tingling.

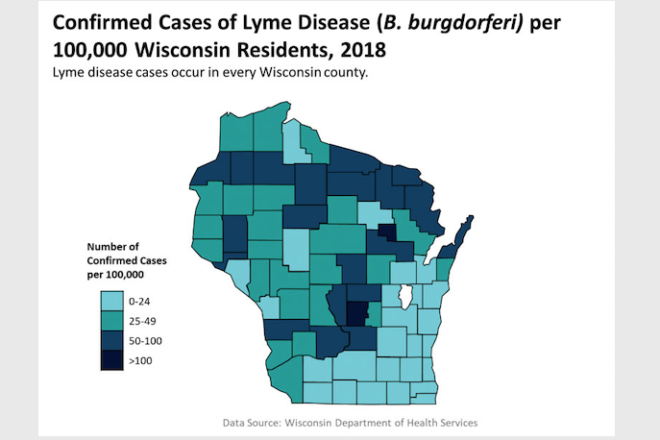

The CDC receives about 30,000 reports of Lyme disease every year, and that could be just the tip of the iceberg. As many as 10 times the number of cases go unreported because Lyme disease is difficult to diagnose and treat. The Wisconsin Department of Health Services reported an estimated 3,105 cases of Lyme disease in 2018, and it, too, suspects the number is much higher. The average number of reported cases has more than doubled during the past 10 years. In 2018, 30 cases of Lyme disease were reported in Door County, compared to just one case 10 years prior.

Small forests tend to harbor many more ticks than large, continuous forests because small forests have larger populations of mice, which are the main culprits in disease transmission, according to Dr. Richard Ostfeld, a disease ecologist and tick specialist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York. Newly hatched ticks attach to mice and other small rodents, obtain the bacterium from their first meal of blood and pass it on to other mammals the following year.

In hosts such as mice, rabbits, voles and foxes, the bacterium spread by ticks is tolerated and does not have negative effects. When humans are bitten, however, the pathogens that the tick injects into the bloodstream result in disease because humans are unnatural hosts.

Differentiating Ticks

• Deer ticks (black-legged ticks) are very small and have reddish-brown bodies and black legs. They transmit Lyme disease and other diseases.

• Adult wood ticks (American dog ticks) are larger than deer ticks and are reddish-brown with silver or white markings. Babies are yellowish-gray. Wood ticks have rectangular heads and mouthparts.

• Brown dog ticks are reddish-brown without any markings and more often attach to dogs than humans.

How to Remain Tick-free

HSHS St. Vincent Hospital, HSHS St. Mary’s Hospital Medical Center and Prevea Health offer these tips to help everyone prevent and treat tick-related incidents.

• To reduce your risk of getting a tick bite, wear light-colored clothing (so that ticks are easier to see), long pants and long sleeves. Tuck shirts into pants, and tuck pant legs into socks. Wear closed-toed shoes.

• Use insect repellents on skin that contain at least 20 percent DEET. Use permethrin-treated clothing and gear, or treat them with permethrin before you hike.

• Stay out of tall grass, brush and heavily wooded areas.

• To properly remove a tick, use tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible. Then pull backward, gently but firmly, using even pressure.

Get the Tick App

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have encouraged people to download a free smartphone app that helps to track and identify ticks. The Tick App – launched in Wisconsin in 2018 – contains information about ticks, asks users to complete a daily log of their activities to assist with research, and allows users to send pictures of possible ticks for identification.