Land & Water Conference: Surface Water Standards a Low Bar

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

In a room filled with, according to Dairy Business Association Director of Government Affairs John Holevoet, “people we’ve occasionally sued and who have occasionally sued us and who are may be involved in litigation right now,” the panel of experts agreed on one thing: standards set forth by the state to protect surface water from excess phosphorus are not very high.

“Certainly, NR 151 [regulation of surface water contamination] is something that’s reasonable for farmers to have to do,” said Paul Zimmerman, director of Government Relations for the Wisconsin Farm Bureau, adding that cost-sharing has historically been a big part of compliance.

“It’s a pretty low threshold,” said Holevoet, speaking about NR 151. “People should already be there. We need to get everyone there as quickly as we can.”

Phosphorus is the primary culprit in surface water contamination, leading to lake and stream dead zones and debilitating algae growth. While NR 217 sets limits on discharge of phosphorus from point sources, nonpoint sources such as agriculture runoff are not regulated by numeric limits and their discharges are harder to track.

“It is in all of our best interest to keep phosphorus on top of our land and out of our surface waters,” said Pat Murphy, retired conservationist with the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

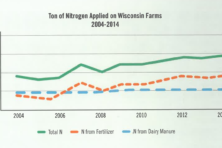

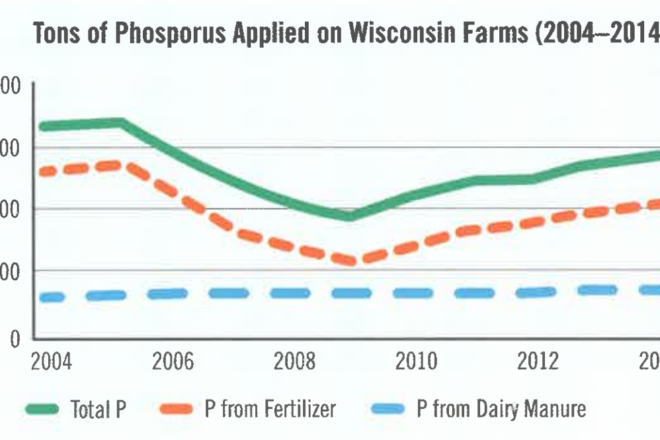

Murphy said a steady increase in use of phosphorus on agriculture land over the past decade, except for a dip immediately after the 2008 recession, could be due to slim profit margins forcing farmers to overload phosphorus in hopes of getting a better crop.

Phosphorus is a necessary nutrient in growth of crops, but excess is likely to leach into surrounding waterways. The panel generally agreed that working with farmers to reduce runoff was more cost effective than treating phosphorus once it hit the watershed.

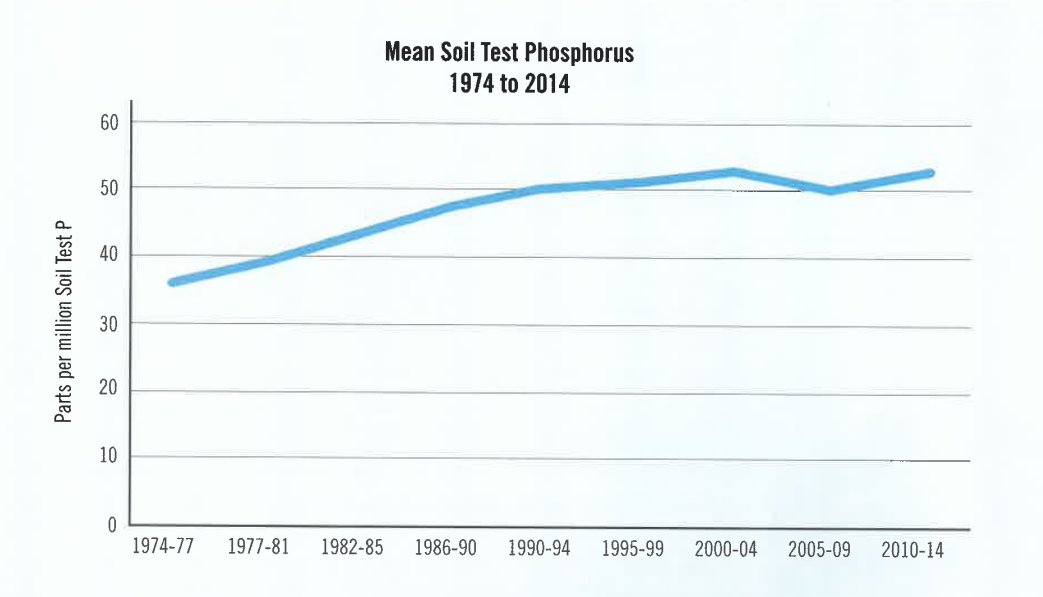

The amount of phosphorus found in soil indicates how much is not being absorbed by crops and is likely to run off into surface water. Phosphorus found in soil has been steadily increasing since the 1970s. Image based on the UW-Madison Soil Testing Laboratories.

Bill Hafs works with NEW Water, the organization charged with branding the Green Bay Metropolitan Sewerage District. He said his organization was attempting to reduce phosphorus going into the bay by one percent. Instead of investing $200-$400 million in a new wastewater treatment plant, he turned to the agriculture industry.

“We think the best way forward is to work with agriculture because it will get us more improvement at a lower cost to us,” said Hafs. Even if remediation in the agriculture community around Green Bay will use taxpayer dollars, it will still be less than a new treatment plant.

Limiting manure spreading is one way to reduce phosphorus runoff, but practices such as cover crops, grass swales in farm fields and not tilling the land can also help reduce runoff. These practices range from no cost to a significant burden to the farmer.

“But in years of low incomes, farmers that see another program that they need to follow and there’s no financial incentive there, they simply will not adopt those things,” said Darin Von Ruden, president of the Wisconsin Farmers Union. “The question is, are there going to be dollars available for it?”

Holevoet said some of the practices are known to increase a farm’s profit after the first few years, but those benefits are hard to swallow short term. Meanwhile, some farms do not have the initial capital to invest in a new practice, even if it is profitable in the long run.

Read more about the topics discussed at the conference.

Kewaunee County in Spotlight for Groundwater Concerns