Le Guin’s Lessons Shine through Science Fiction and Fantasy

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

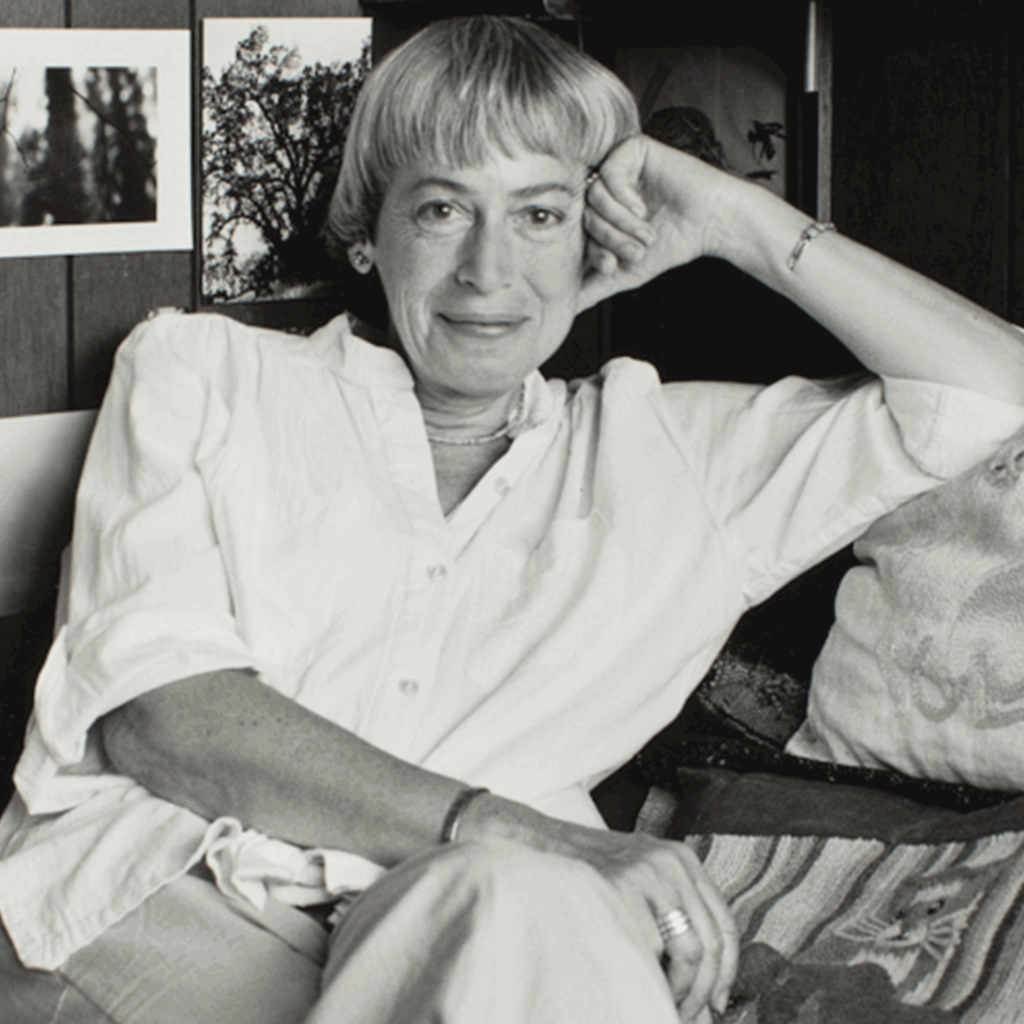

Welcome to a new installment of the Door County Readers series. Twice a month, we invite readers to talk about which books have been most influential to them, their favorite authors, what they’re reading now and more. This week, Logan Thomas shares his newfound appreciation for Ursula K. Le Guin. Let the discussion begin!

by Logan Thomas

I was introduced to Ursula K. Le Guin during the past year. I had been trying to convince a friend that Kurt Vonnegut was the greatest American novelist and that he had been sidelined because he wrote science fiction novels – much like Bradbury and other novelists who liked to use the genre. I have a full bookshelf of Vonnegut at home and have intentionally acquired extra copies of his novels so I can lend them out without fear of damage or loss.

After singing Vonnegut’s praises to this friend for months – and forcing at least three novels onto her reading list – she gave me a copy of Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, and I couldn’t put it down. I can’t say that Le Guin usurped my love for Kurt, but I’ve certainly added her to my ongoing rant about authors who have historically been marginalized as genre authors.

Like a lot of people during the last few months, I’ve returned to reading as one of my primary forms of entertainment, and Le Guin has been one of the most prominent figures on my quarantine reading list. I started with one of her science fiction novels, the fantastic The Dispossessed, and then I delved into her series of novels centered around the fantasy world of Earthsea.

The science fiction and fantasy genres are particularly useful in creating worlds that can be used to speak about our own, mirroring it to talk about issues and themes that our own reality often isn’t ready to face yet. Le Guin uses this toolbox to its best potential.

During the 1960s and ’70s, she was tackling problems that still challenge us today, but she insulated herself by masking these issues in future alien planets and fantasy archipelagos where wizards and dragons can speak the true names of things and change the fabric of their reality.

Le Guin explores gender fluidity and nontraditional relationships through an earthling who’s trying to add a new planet to a coalition in The Left Hand of Darkness, and The Dispossessed explores how two communities with different philosophies can use those differences to produce enlightenment by framing it as two planets engaged in a cold war. (It’s no coincidence that this was written in the middle of the real Cold War and that the two planets were paragons of capitalism and anarcho-communism, respectively.)

The first three Earthsea novels examine a man’s life in the most human of ways: his brashness in youth; his fearlessness and mastery as an adult, which may also prove to be overconfidence; and his eventual acceptance of powerlessness in old age, even though this character is a wizard.

Le Guin knows that in order to connect with readers and find true understanding of humanity, sometimes it’s more important to create stories and settings that illustrate the themes and issues that humanity faces and less important to be writing about humans. Presumably, the human who’s reading the text will make the connection.

These books have all made me think about the world in different ways. I’m lucky to have been introduced to Le Guin at a time when I was ready for the insights in her works. Vonnegut, Bradbury and Le Guin are truly some of the greatest American novelists and do not deserve the qualifier of “science fiction” and “fantasy” before that title.

Vonnegut may still be my favorite author, but my Le Guin shelf has been getting more crowded every day, and I’ve started pushing her novels on friends more and more often.