- Door County

- Door to Nature

- Nature

- Features

- Algoma

- Baileys Harbor

- Education

- People

- Egg Harbor

- Green Page

- Kewaunee

Nature Boy: The Wonder of Roy Lukes

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Editor’s Note: Our esteemed nature columnist Roy Lukes is battling metastatic cancer at his home in Egg Harbor. As he fights, we honor his immeasurable contributions to this publication, his readers, and all those who love the Door Peninsula with a look at the life of the man behind the byline. Thank you, Roy.

In 1964, the board of directors of The Ridges Sanctuary hired their first full-time employee, a young teacher by the name of Roy Lukes. It’s hard to believe any hire was ever a more perfect fit for a job.

The Ridges was not then what it is now. There was no state-of-the-art nature center building, few boardwalks or bridges, and the range lights, now so picturesque, were in disrepair, but Roy was in his element. He immediately set himself to the job of transforming The Ridges into much more than a preserve, documenting the plants and animals that called it home in astounding detail and leading twice-daily tours of the grounds, introducing thousands of people to the wonders hiding amongst the swales. He built bridges, cleared trails, and forged invaluable relationships with guests, donors and schoolteachers.

“I don’t even know where to start,” said Steve Leonard, executive director of The Ridges Sanctuary since 2006. “He just took it to a whole other level with programming. He was so immersed in the sanctuary and put so much of that down on paper. He really turned it into an educational facility.”

I asked Carl Scholz, a Ridges Board member for 35 years, what Roy meant to the facility.

“Everything,” he replied. “Everything.”

Emma Toft and Roy Lukes on the day she handed him the keys to the Upper Range Light in 1968. Photo courtesy of Ridges Sanctuary.

Emma Toft, a founder of The Ridges and one of the county’s most ardent and influential conservationists, knew they were lucky to get a naturalist and manager of Roy’s caliber. He had earned his undergraduate degree at the University of Wisconsin – Oshkosh, served in the Korean War, then earned his Master’s Degree at the University of Wisconsin – Madison before becoming a teacher at the Door-Kewaunee Teachers College in Algoma, not far from the home where he grew up.

Now he was the face of The Ridges, and Emma arranged for him to live at the Upper Range Light on the grounds, a sparse abode the Coast Guard had abandoned two years earlier. The doors barely closed, there was no insulation, and the heat came by way of three stoves. Roy spent his first night sleeping on three sofa cushions spread on the floor, and wrote later that he feared the wind would blow the tower off the house.

But the young naturalist was thrilled by the opportunity, and in 1968 Roy approached Door County Advocate Editor Chan Harris with an idea. “What if I wrote a nature column for the paper, would you run it?” he asked. Harris gave him the go ahead, starting a 48-year run of columns appearing in the Advocate, Green Bay Press-Gazette, Appleton Post-Crescent and Peninsula Pulse, through which he would become the voice of the natural world in Door County and far beyond. Living at the range light, he shared his adventures and observations in print, inviting readers into his experiences with an unsurpassed knowledge and unrivaled joy for the subject matter.

“I think Roy had that passion, that love to begin with, but to have the opportunity to live in The Ridges range light 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, he could live and breathe what the Sanctuary was all about, and he communicated that to his readers,” Leonard says.

Roy’s articles delved into the science behind the habits of birds, the growth of trees, the delicacy of the Yellow Lady’s Slipper, but it is his personal touch that enthralled his devoted readers, a wide-eyed, boyish awe of the natural world that he has never relinquished.

“Usually he would share some information about an animal’s behavior or habitat, but also a story about an encounter that he had had with that animal in the past,” says longtime reader Laura Menefee of Little Sturgeon. “I think his observations, as well as the photographs, enable those of us who are not naturalists to be more receptive and perceptive to the natural things around us.”

“I think everybody was anticipating it,” Leonard says. “What was the new thing Roy was looking at? Maybe they weren’t in Door County, but people felt that they were right there with him at the range light.”

In 2007 he took his columns to the Peninsula Pulse, where co-owner Madeline Harrison was proud to welcome his voice.

“What I came to notice over years of reading his words, week in and week out, is what a tenderness he has toward nature,” Harrison said. “It isn’t all science and biology. There’s something very touching about the way he regards plants and birds and animals – there’s a true kindness there.”

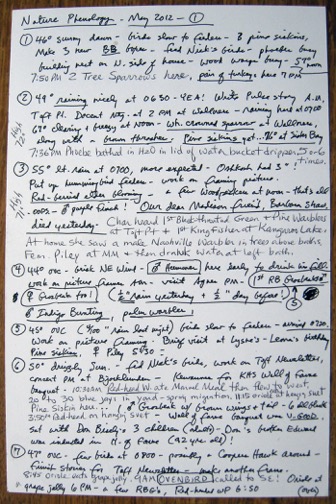

Each day Roy and Charlotte record detailed notes of their observations of the world around them in their daily nature phenology cards, creating an invaluable reference guide to document how the environment of Door County is evolving.

Before the internet, many readers clipped his columns to save as references, piled up in desk drawers, file cabinets, and on desktops, as Roy earned a fan base throughout Wisconsin and far beyond. The column brought growing notoriety to The Ridges, and nature lovers began to clamor to meet him and join him on his hikes.

Talk to people who know Roy, who’ve worked with him or joined him on tours, and only one thing trumps his knowledge of the natural world, and that’s his ability to connect with children. It wasn’t honed in teaching school, but rather it comes naturally to him, most likely because he remains one of them.

As we age, we lament that the little things no longer bring us the joy they once did, crowded out by pressures wielded by financial obligations, family and careers. We wish we could go back in time to those moments in our own lives that seem impossible to experience again. For Roy Lukes it isn’t. At 86, he remains a boy in all the best ways, enamored with every plant, tree, and bird, as curious about their habits as he was as a boy growing up in Kewaunee, the formative years he returns to so often in his columns.

That was when his parents instilled in him a love of nature. His father was a wonderful gardener and mushroom hunter, his mother a lover of wildflowers who would take him down to the river or into the woods to explore, listen to the birds, and admire the power of its trees. Those forays have stayed with him all his life.

As a young adult, Roy observed a huge flock of birds cross in front of his car on the way to class at the Door-Kewaunee Teachers College, and he went home obsessed with identifying them. A new mission was imprinted upon him. “If I was going to teach children, I had better learn about birds and plants and animals and everything else of interest in the out-of-doors,” he wrote.

Years later the author Norb Blei, in profiling Roy in his most famous work, Door Way, was spellbound by Roy’s connection with children. He wrote:

“What I recall more than anything that morning was the constant consideration he afforded my seven-year-old son, always giving him first crack at the telescope or his own pair of binoculars. ‘After all,’ he told us, a group of about 10 adults and one child, all strangers, ‘this little guy is the most important member of the group. He’s the fella we’re going to have to depend on someday.’”

“He thought it was so important to reach children,” said his wife Charlotte. “He’d say that if you grow up not knowing, not caring, then how can you preserve it?”

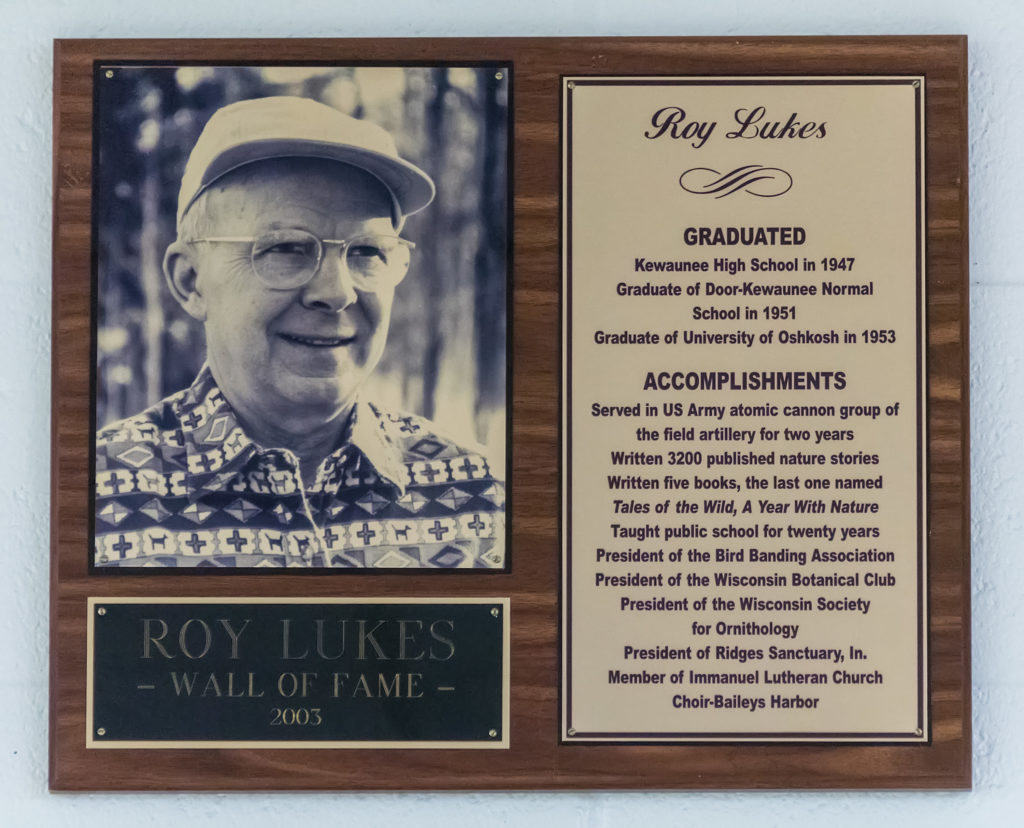

Roy Lukes’ plaque in the Kewaunee High School Wall of Fame. Photo by Len Villano.

After Gibraltar Area Schools decided they didn’t need him as a full-time teacher anymore in 1970, he became an environmental education specialist, visiting all the village schools throughout the peninsula at regular intervals. Teachers marveled at the way he could hold 25 second-graders in the palm of his hand.

“He would get them so quiet that a whole class could sneak up on a bird at a bird feeder,” said Mike Madden, who taught at Sevastopol for 35 years and credits Roy as one of the reasons he became a teacher. “I think it was his integrity and sincerity, and something special about his deep, masculine voice and the way he delivered his words. If a child came up to him and showed him a small rock, they would walk away thinking it was the most special rock in the world.”

When he wasn’t wooing them with his quiet sincerity, he was mesmerizing them with his excitement about a new discovery.

“He could get so excited working with children, I’ve seen him jump up and down and yell ‘whoopee!’” Madden says.

Those students from so long ago remain inspired today. Not long ago Steve Jorns, an old student from Egg Harbor, called the house to see how Roy was doing.

“He told me that Roy once took the class out into the woods,” Charlotte said. “Roy stopped and quieted the class before whistling a bird song, and out of the trees a bird came down and sat on Roy’s shoulder.”

“Was it a chickadee?” Charlotte asked him, knowing it was.

She knew because it was a trick Roy learned from Emma Toft, one of the greatest influences in Roy’s life. She taught him the art of luring Black-capped Chickadees and Red-breasted Nuthatches to his hand for food, which he would use to create one of Charlotte’s favorite memories of their courtship.

They met in 1971, when Charlotte visited Baileys Harbor from her home in Milwaukee. She joined her friend on a hike at The Ridges, but she had to borrow jeans and a flannel shirt from her friend’s husband. That day she met Roy, clad in his old Army shirt, threads dangling from its cuffs, his hat stained, his work jeans full of holes. She saw him again at a presentation soon after, was awed by his photographs, and when Charlotte returned to Milwaukee they began exchanging letters, then visits.

For Christmas Roy gave her a bird book, binoculars, and a special hat for hiking. He didn’t give her a ring, but he invited her up to Baileys Harbor for New Year’s Eve. Charlotte made dinner for Roy and some friends and Roy invited her to breakfast the next morning.

“Wouldn’t it be great if you lived up here all year?” Roy asked her at the Range Light.

“Where, at the Nelson Motel?” she replied, referring to the only hotel open in the winter.

“No, here at the Range Light,” he said.

“Yeah, but wouldn’t the neighbors talk?” Charlotte replied.

And that’s when Roy asked her to marry him. She said yes, and they went snowshoeing out to Toft Point, Roy’s favorite place. “Roy had this red woolen hat on,” Charlotte said. “He told me to take my gloves off, and then he put birdseed in my hand, and he began to whistle. And this bird, a chickadee, comes and lands on his hat, crawls down his arm, and eats the bird seed out of his hand.”

Roy Lukes with his “partner in nature” Charlotte. The two have been inseparable since they met on one of Roy’s guided hikes at The Ridges Sanctuary in 1971. Photo by Len Villano.

That day Roy secured himself not just a wife, but an editor for life and his “partner in nature,” one who revered the natural world every bit as much as he did. In time, few would mention Roy without mentioning Charlotte, the pre-eminent mushroom expert of Door County and the rock that Roy leans on to this day, as his health declines.

He can no longer drive or embark on the spur-of-the-moment adventures he loves so much, those that come when a reader or friend calls with a question – “What is this bird, what is this sound?” – or to suggest he measure a tree, or, as Nick Anderson once did, to tell him that a beautiful Northern Hawk Owl had just landed in his yard.

“I’ll be right over,” he told me. “He was excited, and he and Charlotte raced over to our house and took pictures. He loved it, really loved getting those calls from people.”

“It was kind of like people giving you ideas of something new to explore or investigate,” Charlotte said. “You can’t be everywhere, so it helps to lead you in a new direction. We’ve met so many wonderful people who are interested in the same things we are, kindred spirits.”

“He talks longingly of the times that he could go into the woods and wishing he could get back on his feet and go measure some big trees,” Anderson said. “This last year, he couldn’t drive anymore. I called him up and said, ‘I’m heading to Toft Point, you better come along.’ He’s so close to that place. Every time he’s out there he’s transformed back to those early days of his life and helping Emma. It’s so important to him. He’d have a camera along, capturing every moment, just revitalized, and he’d take a deep breath being in the presence of what he worked so hard to preserve. It was magical being out there with him.”

As his energy waned last year Charlotte thought it might be time to stop writing his column. But Roy said no. As long as they can write it together, he wants to keep the columns coming, keep sharing his observations with the world, culled from decades of detailed daily journals of his observations. So for the last several months, Charlotte has reviewed his old columns and updated them with new observations, getting Roy’s approval at the dinner table, their byline now shared.

His article count now stands at a little more than 3,000, chronicling the environment of the peninsula as few others have chronicled any place. He has written five books and received at least 19 awards for environmental advocacy and stewardship, including most recently the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology. He’s proud of the columns, the books and the honors, but only in their role in reaching a greater goal.

“I think he’s most proud of just being able to help teach people about nature,” Charlotte said. “It’s rewarding to him when people tell them how he’s improved their lives by making them aware of the world around you. He’s proud to have helped the average person love nature.”

Roy Lukes on the grounds he knows better than anybody else, leading a tour celebrating the 75th anniversary of The Ridges Sanctuary. Submitted.