Never Forget: Veterans Day

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

By Mike Shaw

“If anyone’s good at following orders, it’s going to be a veteran.”

With those words, Beth Wartella, a former U.S. Navy enlistee and now Door County’s veterans service officer, described why those who have served in the military should have little trouble abiding by strong stay-at-home advice this Veterans Day, however reluctantly. It’s because the “generals” in the ongoing pandemic war – doctors, nurses and researchers – say so.

But although the coronavirus may have the power to cancel the special day’s traditional in-person observances, it can’t erase the emotions and memories that Nov. 11 conjures.

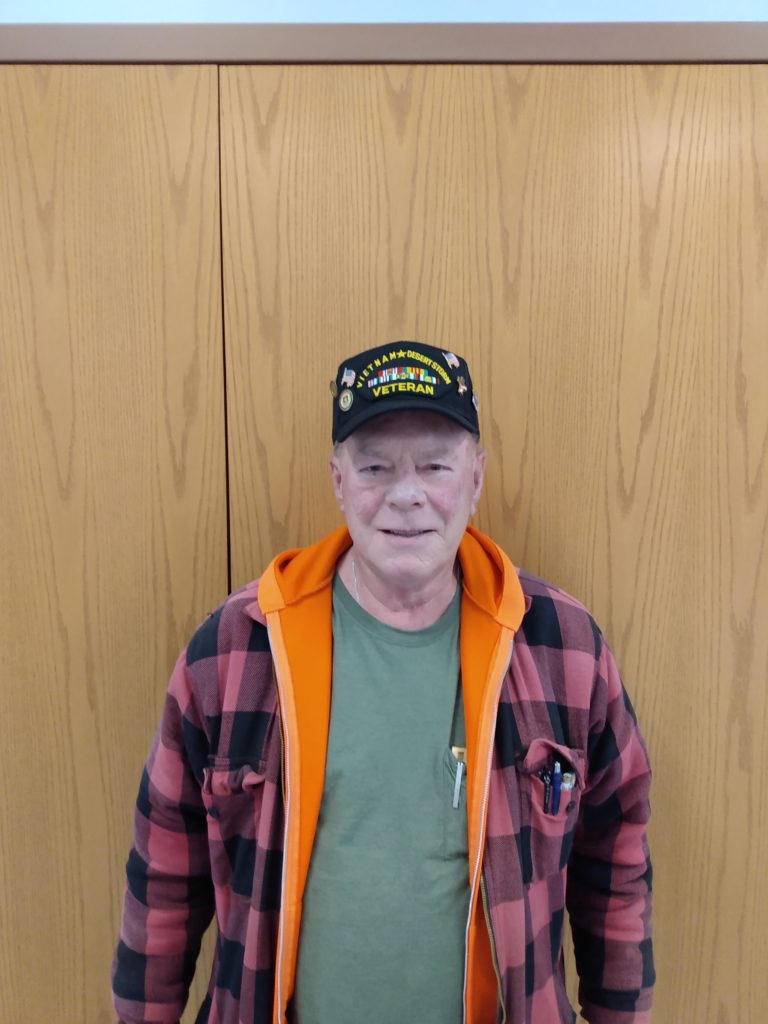

The Peninsula Pulse spoke with two representatives each from two generations of Door County veterans during a recent group interview: Wartella and her assistant, Nathan LeClair, who served during Operation Enduring Freedom, known popularly as the post-9/11 War on Terror; and Bob Gamble and Dennis Ott from the Vietnam era.

Ott hails from two military branches, reenlisting in the Army about a decade after his late-1960s Air Force combat tour in Vietnam, later retiring as a “career military man” in 1994.

Veterans Day: By the Numbers>>

The Hidden Casualties of War>>

Devotion to Duty: Norman Carrol Recalls Life in the Pacific>>

Door County’s Final Civil War Veteran Remembered>>

“When I was little,” Wartella said, “our older church members would wear their military uniforms to church [around Veterans Day]. How they still fit into them, I don’t know. But being exposed to that as a child, and getting a good perspective on what it means and to fight for your country, that’s where it was all instilled.”

LeClair has a great-grandfather who suffered through the Bataan Death March during World War II and an uncle he never knew, Phil Overbeck, who died while serving in Vietnam.

“Every single day, at some point in the day, I think of some of my friends who I lost [in combat],” LeClair said. “On Veterans Day itself, I call about six of them who are still around and chat.”

Gamble recalls his childhood experience of school classes pausing to recite the Pledge of Allegiance at precisely 11 am each Veterans Day. The class then turned to the east – toward Europe, symbolically – to commemorate where and when the armistice ending World War I took effect.

The Nov. 11 date was chosen for Veterans Day to mark that “11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month” when the ceasefire for the War to End All Wars occurred.

Gamble comes from a family with “everyone in the military,” so he did not need to be forced into the service through the draft. He never served “in country” during his Vietnam-era Army tour from 1964 to 1967, but he cites statistics showing that every combat veteran depends on seven supply and support personnel to do his or her most risky jobs.

Part of his time was spent helping to establish a training battalion at Fort Benning, Georgia. He laughs at memories of his laidback unit’s culture clashes with the more buttoned-down, poster-perfect soldiers of Fort Benning.

“It was a pretty gung-ho base, and we were engineers [by training],” Gamble said. “So they didn’t like us coming down there with our sloppy fatigues and our shirts hanging out.”

Gamble also salutes the unofficial homefront veterans who get America through the grinds of its wartimes, noting that his father-in-law could not enlist during World War II because he worked as a lead machinist at the Manitowoc Company shipyard – a job that was deemed too essential to vacate.

Ott’s half-a-lifetime in the military spanned from Vietnam to Operation Desert Storm, from combat operations in the Far East to managing enemy prisoners in the Middle East.

As part of the generation that fought the bitterly divisive Vietnam War, Ott belongs to the only group of American overseas fighters who returned home to protests and insults. He blames the ugly homecoming partly on what he called one-sided press coverage that focused on carpet bombings of North Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia but ignored the off-duty humanitarian efforts by Ott and his unit.

“We took up a clothes collection for an orphanage there, and only [the chain store] Montgomery Ward ever responded to us,” Ott said. “It was that controversial. I mean, we didn’t even get rejections – nobody ever responded.”

Ott believes in a peacetime draft or, preferably, mandatory military service for at least two years. It’s not unheard of around the world: democracies such as Norway and Switzerland still use the draft, and it was just during this century that Italy got rid of compulsory military service for all.

Because of its huge population, the United States, like China, has never needed a draft to fill its peacetime military ranks. Instead, Ott views military service not in terms of maintaining troop numbers, but for its value in bolstering feelings of loyalty and patriotism toward the country.

‘That will never happen to another veteran, ever’

Ott’s three fellow veterans agreed that he and his contemporaries were at a disadvantage by returning home as individuals rather than with their units. Wartella and LeClair arrived back on home soil to applause, marching bands and cheering family and friends.

“I think the Honor Flights we’re doing now and those [types of receptions that] Nate and I received, it’s almost like an apology from my generation to yours,” Wartella said to Ott. “We have a sense of making up for that lost recognition.”

“We all made a commitment that that would never happen to another veteran, ever,” Ott said of his fellow Vietnam vets.

Ott and Wartella both said their time in the military gave them an appreciation for cultural and racial diversity because each individual had to put her or his life in the hands of every other team member.

“During my first holiday season spent in the Navy, one of the [African-American sailors] said the holiday always meant eating black-eyed peas,” Wartella said. “I had never encountered any answer like that from my background. They all become your ride-and-die buddies.”

Wartella held top-secret security clearance while working in security at an intelligence base in Sugar Grove, West Virginia, from 2008 until 2011. LeClair held naval posts from 2005 until 2013 as an aviation technician, base security officer and bow gunner on anti-piracy patrol boats in the strategic Straits of Hormuz. The latter assignment helped to keep supply and naval shipping lanes open for American forces during the War on Terror.

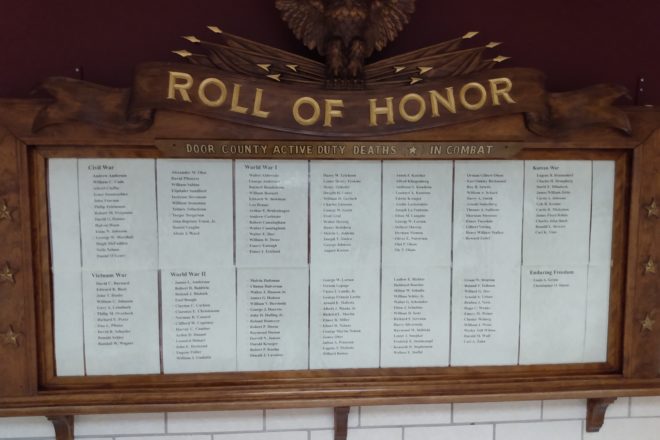

Wartella estimates that fewer than two dozen World War II veterans are still alive in Door County – an area with about 2,000 veterans in all. A total of 172 Door County residents died while on active duty in America’s conflicts from the Civil War to Enduring Freedom. Seventy of those war dead succumbed to disease, auto accidents or other causes of death, and 102 fell in combat.

“Every day is Veterans Day for me because I work with such a great group of people who come back and contribute to their communities,” Wartella said. “I see the American flag flying [on the county office grounds] every day, and realize I still have an opportunity to push myself. I hate exercise – I hated boot camp – but now when I’m working out or running and exhausted, I can keep going, knowing there are so many who no longer have that option.”