Philip Graupner, A Man of Letters

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

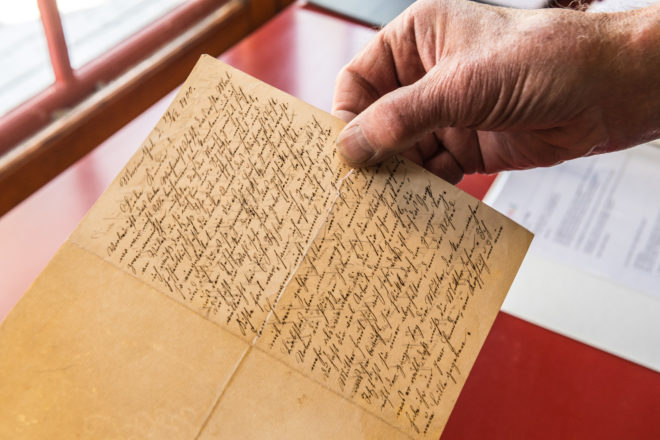

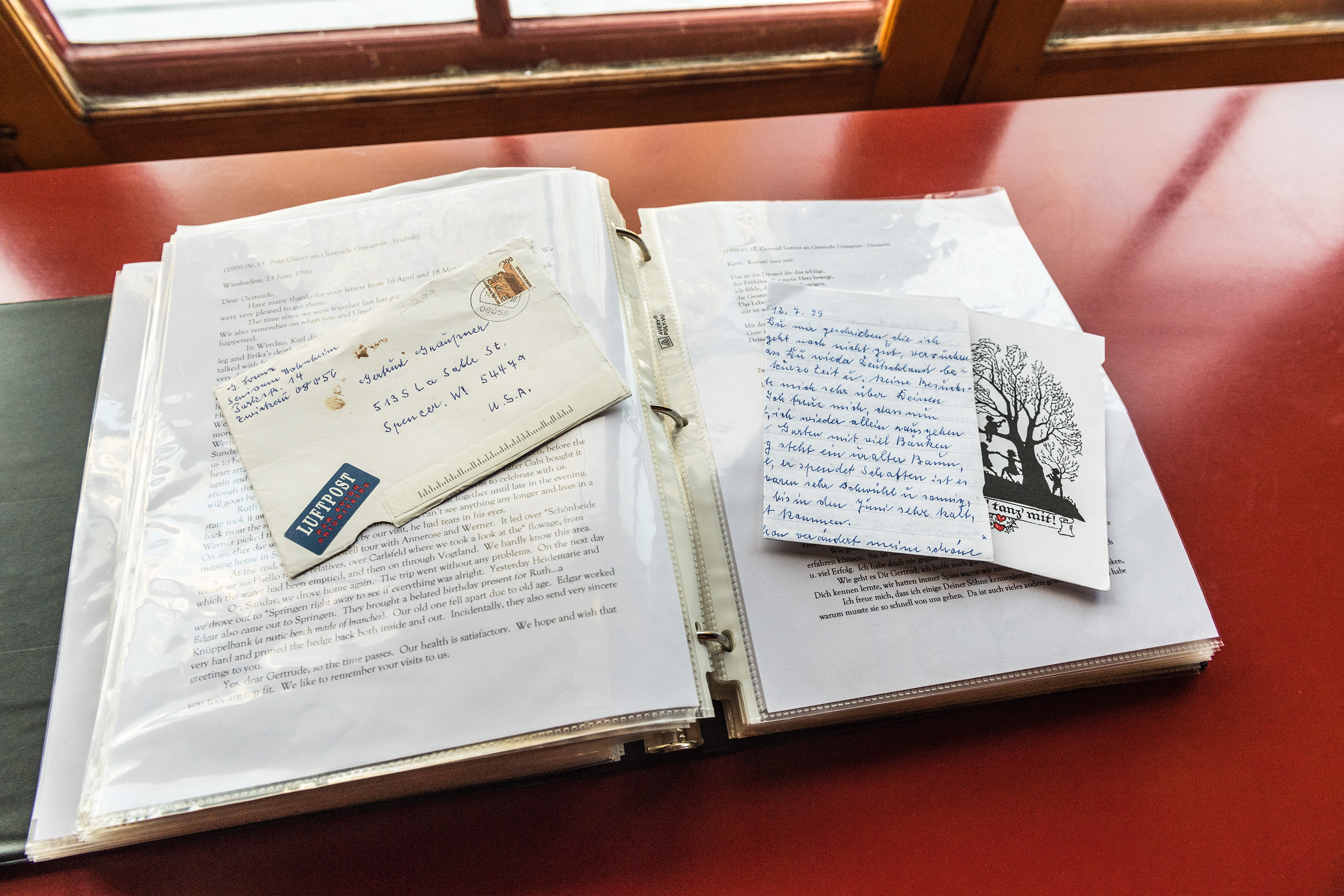

A man of letters, indeed – there are nearly 1,700 of them in what Philip Graupner calls “The Graupner Letter Collection.” Each letter is in its own transparent cover, along with the original stamped envelope (except for the stamps Graupner’s mother clipped off for her church’s collection).

The 27 large binders in which the letters are filed chronologically by family fill seven feet of shelving in the glassed-in porch of his home on Highway Q. There are another 10 binders with letters from Graupner’s mother’s side of the family and other distantly related families.

The first letter was written Dec. 29, 1900, by Selma Auguste Gläser of Marienthal (now the town of Zwickau in East Germany) to her oldest daughter, Anna Gläser Graupner, who married C. Hermann Graupner the previous June and moved to the Ruhr region near Essen.

And there begins the tale of the Graupner family letters. Anna and Hermann had seven children: Anna Selma (1901), Ida (1902), Elsa (1904), Hermann, Jr. (1906), Karl, also called Carl, (1908), Paul (1911) and Johanna, usually called Hanni, (1919). Hanni was the only one of the seven who never married. The others all had children, and there were dozens of aunts, uncles and cousins on both sides of the family – many of them prolific letter writers, too.

Because of the effectiveness of the British blockade, WWI meant “hunger years” for civilians, and the time after Germany’s defeat was marked by political and economic upheaval. In 1917, Karl signed up to spend his vacation working on a farm in Pomerania, several hundred miles away on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. Although he was only nine, his parents allowed him to go because there wasn’t much to eat at home. And worse was to come. Reparations enforced by the winning forces in WWI led to hyperinflation. A loaf of bread that cost 250 marks in January 1923 had risen to 200,000 million marks by November. Letters spoke of having to carry money to the store in a wheelbarrow.

In 1923, Ida and Karl, ages 21 and 15, immigrated to a farm near De Pere, Wis., owned by their mother’s first cousin, Frank Boser. Siblings Elsa and Hermann, Jr., 21 and 19, followed them to Wisconsin in 1925, soon after the marriage of their sister Anna to Adolf Beckers.

Elsa and Ida found jobs in Milwaukee. In 1928, Ida married a German immigrant named Willard Liepert, and they took over his family’s farm near Boltonville. Elsa married August Dauer after they returned to Schlangenbad, Germany, at his father’s insistence, to take over his cabinet-making shop. Hermann. Jr. married Malinda Bloedorn in Greenleaf, Wis., in 1938, and Carl married Gertrude Boock, a Lutheran schoolteacher, in Spencer, Wis., in 1939. Paul, an engineer, married Gerda Scheidhauer in 1938, and they remained in Germany, suffering terribly during WWII. Hanni, the youngest, cared for her parents through their old age.

It fell to Carl’s son, Philip, to preserve the Graupner family’s voluminous correspondence. Many of the letters were saved by the siblings who came to Wisconsin, but because there had been a major change in the style of handwriting during the years, later generations could not read them.

Philip, who majored in German at the University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point, later lived in Germany from 1965-69 and attended commercial art school in Wiesbaden from 1966 to 1968. After that he worked in the bookbinding department of a publishing company until 1969, when his passport expired. After the death of elderly relatives there, he went back to Germany to save hundreds of letters and photos that would have been destroyed.

Back in the U.S., Philip enrolled in the new School of Design at UW-Milwaukee. While a student there, he rented living quarters in the home of Irene Haberland and her daughter, Anne. When they moved to Door County in 1969 so that Anne could open Edgewood Orchard Galleries on the 80-acre cherry orchard on Peninsula Players Road, Philip came with them. He and former classmate, Minnow Emerson, an artist and architect, worked at the gallery in the early years, and Minnow later married Anne.

Like the Emersons, Philip remained in Door County. When Lutherans in Baileys Harbor built a new church in the early 1980s, he got permission to take down the original 1890s church and used the lumber to build his rustic cabin on Highway Q. Letter translation became Philip’s hobby. His occupation was designing and building homes, mainly with Jeff Ward and also for a while with Paul Sterenberg. They built 27 new homes, along with remodeling, additions and homes designed by others. He retired in 2009 to focus entirely on the letter translations. In 2014, he self-published a translation of a book about the Civil War written in German by an artillery officer who was a German immigrant.

He’s spent the past 21 years translating the hundreds of family letters and compiling 58 of them, dated from 1900 to 1948, in a 227-page book, Letters of the Graupner Family, divided into seven sections: The First Letter, Immigration Period, Courtship Letters, Depression Years & Starting Families, World War II and Post-War Period. The book ends with three long narratives.

The first, dated June 30, 1948, is a letter Paul Graupner sent to the Women’s Guild of his sister’s church in Wisconsin, thanking them for the help they had provided to his family during the war. The danger and hardships Paul and Gerda endured are hard to imagine. Knowing she was at risk of being captured by the Russians, Paul walked 300 miles across the Alps, staying above 6,000 feet to avoid enemy troops. By the time he found Gerda, she hardly recognized him. His clothes were remnants of old army uniforms; his unmatched shoes were from two amputees.

In the second narrative, Ida’s son, Gerald Liepert, recounts his experience after WWII, caring for livestock being shipped to Europe by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency to feed thousands of starving people. The “sea going cowboys” were paid $150 for each round trip. Delayed by a strike in Newport News, Virginia, from starting his first voyage, Gerald got a job in a restaurant, working 16 hours a day for $8 a week and meals.

The third narrative is the story of the trip Gerald’s aunts, Elsa Graupner Dauer and Hanni Graupner, made in 1946 to meet him in Bremen, Germany, when his ship docked to unload livestock. The aunts had never seen Gerald, train travel was very erratic, lodging was scarce and food was available only on the black market or with ration cards that could only be used in one’s home area. Bremen was three occupation zones (American, French, English and American again) away from the aunts’ home in Schlangenbad. But the determined ladies made the trip and visited with their nephew for eight days, sleeping in a corner of a room in a mostly-destroyed house and trading cigarettes for bread.

Access to the entire collection is available on request to Philip Graupner, 920.839.2227 or [email protected].