Prohibition Era in Door County

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

As the harsh Door County winter settled in shortly before Thanksgiving in 1933, John R. Seaquist addressed the Door County Council of Religious Education at the Ephraim Moravian Church. On that 19th day of November, just two weeks before the repeal of the 18th Amendment would be ratified, Seaquist pledged his organization “to do all in our power to keep our county and community as clean from the liquor evil as possible, thereby showing our determination in a crooked and perverse generation.”

It was fitting he gave his speech in Ephraim, a village founded as a Moravian community and dry town by Rev. Andreas Iverson, a man very much opposed to drinking. In this setting, Seaquist continued his diatribe: “During the ages that have gone by many forms of evil have blighted mankind but no scourge has been more persistent or destructive than alcoholic drink,” Seaquist raged. “War is the only other agency that can even approximate it in woe and misery produced.”

And in another dramatic plea, he proclaimed, “The vigilance of the faithful who are still in favor of prohibition must then be even more true to the cause.”

But the vehemence of his call to arms would gain no traction. How could it? Like the rest of the nation, most Door County residents had not spent the Prohibition years walking with chest-puffed pride in their national temperance, but instead had spent those long 14 years exploring every route to circumvent the doomed law.

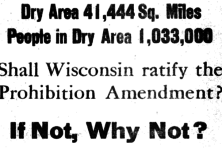

Supported by groups like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Anti-Saloon League, the League Against Alcoholism, and various church organizations, Prohibition became reality December 18, 1918 with the passing of the Volstead Act. When the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified January 16, 1919, the ban on drinking went into effect and was announced to the Door County populace through a Door County Advocate headline proclaiming simply, “Nation Will Be Dry.”

Not for long.

Almost immediately criminals and average, innocent Americans went to work investigating ways to skirt the law. In Chicago, Al Capone would become as integral to the city’s image as the wind and the lake, unleashing a decade of Tommy guns, murder, and corruption upon the city. It has long been rumored that Capone, when the noose of the law got tight, would escape to the sparse roads and villages of the peninsula, but it was another Chicagoan with a brewing past who planted the deepest roots in the Door.

Robert ‘Doc’ Wahl was a chemist who was born in Milwaukee. He ended up in Chicago, where he put his considerable skill to use developing standards and procedures for beer brewing that remain in use today. In the late 1890s he partnered with Max Henius, another chemist and founder of the American Academy of Brewing, to open the Wahl-Henius Institute of Fermentology, where major breweries would send aspiring brewmasters to get schooled in the neglected science of beer making. The school would become recognized as the leading source for all things brewing, and Wahl would author three books on the subject which remain well-referenced guides for home-brewers and experts alike.

The Volstead Act had an incredible impact on breweries, distributors, and tavern owners throughout the country. In Sturgeon Bay, it was estimated the law would cost the city $6,500 in taxes and fees charged on taverns in the first year alone. But perhaps nobody was so affected as Wahl, for when one has devoted himself so completely to something as to open his own institute, a law prohibiting that devotion is tough to stomach.

When Prohibition passed, Wahl closed his institute, packed up his life, and did what so many Chicagoans continue to do – retired to Door County. He bought a large orchard behind what is now Ray’s Cherry Hut, but it’s said he didn’t devote himself solely to cherries and apples.

Bob Armbruster recently purchased the land where the remnants of Wahl’s orchard now reside, crumbling in decay from almost three decades of neglect, but a popular subject for painters and photographers still. When he first looked at the property he found one aspect particularly curious. “I thought the windows ringing the top of the silo were a bit strange and asked why they were there,” he said. “I was told they were for lookouts in case the feds came to bust up old Doc Wahl’s bootlegging operation.”

Armbruster was told a few stories about the property, where Wahl was rumored to have set up shop moon-shining amidst the dirt rows and seclusion of modern-day Juddville. Fascinated by the tales, Armbruster began digging, finding scraps of information about Wahl in old newspaper archives and numerous references to Wahl and his institute online. He muddled around the property and found dozens of bottles, some dated from 1919. Many fit the mold of the type Wahl would have used to bottle his concoctions three quarters of a century ago.

For 13 years Wahl lived on the orchard, continuing to hone his craft and increase his knowledge base. When the dry era ended in 1933, Wahl wasted no time getting back to legitimate work, re-opening his Chicago institute, where he worked until his death in Chicago in 1937.

Wahl was an expert, but far less knowledgeable folks endeavored in brewing of all sorts. After passage of the Volstead Act in Wisconsin, a newspaper article began, “It was on this day and date that King Barleycorn was condemned to death,” but Barleycorn proved a resilient old monarch who would not have his last breath easily taken.

Federal Prohibition Director Thomas Delaney tried to scare off efforts to circumvent the law with a stern announcement of the punishment awaiting those who would break it, which prohibited the manufacture of any product for beverage purposes containing one half of one percent or more of alcohol by volume. For a first offense, the penalty was not more than $1,000 ($10,704 in today’s dollars) or imprisonment not exceeding six months. A second offense brought a fine not less than $200 ($2,140) or more than $2,000 ($21,408) and imprisonment of no less than one month or more than five years.

These were no small fines, but his admonishment proved little deterrent to those with the thirst. In his book Discovering Door County’s Past, local historian Marvin Lotz said, “Even though alcoholic beverages had been outlawed by the federal government, they were still plentiful.”

Walt Jorgensen was a young boy on Washington Island in the waning days of Prohibition, but recalled the era from early memories and stories passed on. “Everybody had stills,” he remembered. “We had one.”

Tavern owners were resilient as well. Frank Tachovsky remembered his father-in-law, Ralph DesEnfants, as a bit of a flamboyant character. A European immigrant, DesEnfants joined Theodore Roosevelt’s White Fleet, the famed Naval division, at age 17 and in its service he saw and experienced much more of the world than the average Sturgeon Bay man of the time. “He had traveled the world and that made him a different kind of guy,” Tachovsky says. “Back in those days, people hardly went to Green Bay.”

DesEnfants and his wife Margaret bought the National Hotel from her parents in 1918, then bought the nearby Shimmel Grocery Store in 1928, where DesEnfants continued to bolster his reputation as a canal city character. The couple remodeled the grocery store into the Hotel Roxana, named after their daughter. In the basement he would operate a bar called The Snake Pit, one of many such underground, behind closed doors, or otherwise politely disguised taverns in Sturgeon Bay at the time.

They formed a modestly covert league of bars who worked together to limit the success of federal agents’ attempts to root out the bootleggers and producers of spirits. Tachovsky described the early years after passage of the Volstead Act, when the feds would ride into town and stop at the first place they came to. In Sturgeon Bay, that was the Y Inn Tavern.

“Once they’d hit the Y, of course the phones would buzz all over town and the other places would shut down and hide their booze,” Tachovsky remembers. “Then the feds would raid the other places and not find any booze.”

Eventually they got smart, switching to “full raids,” when agents would hit all the taverns at once, a strategy Tachovsky’s in-laws found difficult to combat. During one such raid, Margaret received the usual warning call and, following standard procedure, hollered downstairs to her husband, “Ralph, the feds are coming!”

“I know dear,” Ralph replied. “They’re down here right now.”

DesEnfants had a counterpart of equal repute on the northern tip of the county, and though Wahl was called ‘Doc’, it was this Washington Islander who was the licensed physician. Captain Tom Nelsen earned himself a seat at the table of Door County legends with a sly bit of conniving that endeared him to islanders 80 years ago, and to the rest of us with a story that regales to this day.

Nelsen came to the island from Denmark in the late 19th Century and bought the building that became Nelsen’s Hall in 1907. Jorgensen knew him in later years and described him as your “typical stubborn old Dane,” a description which must have held substantial truth, as Nelsen wasn’t about to let a little thing like a Constitutional Amendment close down his bar.

Perhaps Nelsen had noticed a small aside at the end of Delaney’s explanation of the Prohibition law published in the Advocate which read, “Druggists only may receive a permit to sell liquor at retail and licensed physicians only actively engaged in the practice of such profession shall be given permits to prescribe liquor.”

Nelsen had seen bottles of Angostura Bitters, a 90-proof Venezuelan recipe, on the medicine wagons of the day and knew it was commonly used as a reliever of stomach pains (the Angostura label on the bottle itself hails its contents as a “pleasant and dependable stomachic”) in addition to its more common use as a flavor enhancer for food and alcoholic beverages. Those who’ve drank bitters straight know its name is more than well-earned, and the powers that be never bothered to ban its importation because, in good sense, they never thought anyone would drink the stuff as a beverage in itself. But they underestimated the thirst and ingenuity of the islanders, particularly Tom Nelsen.

Nelsen went out and got his pharmacist’s license, which was easier to come by in those days, and began “prescribing” shots of bitters to his “patients” at the bar. Nelsen himself was known to drink a pint of bitters a day, the mere thought of which would inspire nausea in those who know its flavor.

It’s said that nobody on Washington Island ever got convicted of selling alcohol, in large part due to geography. In the days before regular ferry service they would see few strangers, and when they did come, they usually came on a boat courtesy of locals, who would send a signal to the shore if they suspected a federal prohibition agent was aboard. But they did come close to breaking up Nelsen’s racket once.

The story goes (with minor variations depending on the teller) that a state agent sat at Nelsen’s bar and saw him pouring some strange liquid into shot glasses, then watched as patrons slid them down like one would a shot of alcohol. So the agent went behind the bar to check the bottle and found it was 90-proof Angostura Bitters. Logically, the agent took him to court for selling liquor without a license.

Herman Lisom, a lawyer married to a woman from the island, took on the task of defending Nelsen. In his preparations, he took a bottle of Angostura and brought it home with him, tasted the substance, and immediately exclaimed, “By God, they don’t really drink this stuff?”

But that bitter taste sparked an idea for his defense of Nelsen – he simply argued the stuff wasn’t fit to drink as a beverage, and subsequently, that Nelsen could only be serving it for medicinal purposes. They say the judge tasted the stuff as well, agreed with Lisom, and threw out the case.

Nelsen went back to his island tavern and continued dispensing the aromatic bitters with the “delightful flavour” to his patients, making Nelsen’s Hall and Bitters Pub the only Wisconsin tavern to operate through Prohibition. By the time the nation became “wet” again in December 1933, the drinking of bitters had become such a habit on the island that many continued to take a shot with their beer, and around 1950, Nelsen’s nephew Gunner started what ranks among the least exclusive clubs in the country, the Bitters Club.

The club claims about 10,000 new members annually who earn their stripes simply by taking a shot of bitters in the pub, helping the island dispense more bitters per capita than any other place in the United States. After choking down a shot, one literally becomes a card-carrying member, which earns one consideration as “a full-fledged Islander…entitled to mingle, dance, etc. with all the other Islanders.” It doesn’t tell you whether that’s a good thing or not.

The impending demise of the effort to dry out the country only re-invigorated Seaquist in the era’s waning days. “We have to enlighten them of the dangers at hand,” he warned. “‘Save the boy, (we need to sing) Save the boy, Save him from the curse of rum.’ And we add, the girl too. May we be able to save them!”

The policy had been a success, he proclaimed, and its failures were due to the fact that “enforcement of the law fell, in altogether too many instances, into the hands of those who wished this policy to fail.”

But Seaquist failed to grasp that those who wished the policy to fail were many, that perhaps the fact that men were willing to go to such lengths as Wahl and DesEnfants, or drink the bitter juice dispensed by Nelsen, was indicative of just how doomed Prohibition was.

Prohibition in the United States:

The United States entered its “dry” era with the ratification of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution on January 16, 1919, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within or into, and exportation out of, the country. It went into effect exactly one year later.

The National Prohibition Act of 1919, more commonly referred to as the Volstead Act after its sponsor, Rep. Andrew Volstead, enforced the amendment and defined the terms “beer, wine, or other intoxicating malt or vinous liquors” to mean any beverage with greater than .5 percent alcohol by volume.

The act was repealed by the 21st Amendment, ratified on December 5, 1933, though several states maintained Prohibition within their borders for years, with Mississippi being the last to go “wet” again in 1966.