Questions & Artists: Chris Daynes (Part II of II)

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

This is part two of my interview with English painter Chris Daynes.

I first learned about Chris Daynes when I purchased a DVD from The Artists’ Place in McKinney, Texas. The Artists’ Place is the United States distributor for Town House Films. Their DVDs feature international artists, many from Britain, painting in various European locations.

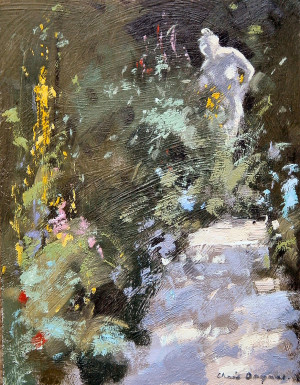

Mr. Daynes has won many awards for his paintings and I think he understands how to reduce a scene to its essentials as well as any artist. His painterly style is pleasing and his colors are wonderful. His answers to my questions were given in a thought-provoking manner and I think you will enjoy this two-part interview. His website is chrisdaynes.co.uk.

Randy Rasmussen (RR): Some of the great artists I have interviewed have said they think there is an ability within that can be developed, but some have more ability. Do you agree?

Chris Daynes (CD): Everything exists in degrees I suppose, including a talent for different things, but whatever it is, it has to be developed. I personally think that the earlier that process starts the better. I taught young people aged between 11 and 18. Some showed more aptitude than others right from the start, but there wasn’t one who couldn’t engage with visual art and benefit in some way, and vastly improve their performance over time. For a few it became a passion, and like me before them, a path for life. The trick is to turn a child’s ‘aptitude’ into something tangible; a result that they can believe in and through which they build their confidence and self-esteem because they discover, sometimes to their surprise, that it’s something they can do well and they like it, thus art is life-enhancing. Underpinning this whole process is a rigour and a discipline, both academic and personal, and the need for the ‘grammar’ of the language to be taught by means of a properly designed art curriculum. Good teachers are those that care for their pupils first and foremost, and will command their respect by demonstrating a depth of knowledge in their subject. Furthermore, youngsters will interpret high expectations demanded of them as a compliment, an affirmation of the esteem you should hold them in. I make no apologies for saying this because I feel strongly about it, and I could say much more about the privilege it is to teach. Of course it’s not all roses and they say that absence makes the heart grow fonder. I’m not sure that I would relish being thrown into the fray at this point.

RR: I found you through The Artists’ Place, which is the United States distributor for Town House Films. Your technique, colors and demeanor on your DVDs were wonderful. I was so impressed I actually bought a DVD for one of my painting friends. How were you selected by Town House?

CD: I think you’ll have to ask Malcolm Allsop of Town House Films that question, because I have no idea. I think he just telephoned me out of the blue. The idea of making a film quite appealed to me because as an art teacher and artist your job is to inspire others to share your life’s work with you. I envisaged the films as just that. That kind of interaction can happen anywhere in my experience. I know some painters who dislike an audience, but I rather like it and see it as an opportunity to promote what we do, and to suggest that all things are possible. Have you ever painted in a field of cows? You’re at one end of the field and they’re at the other. They see you, gradually work their way towards you, and end up licking the paint box. Humans are similarly curious. They just have to come and look, and I’m disappointed if they don’t. Oddly, the public keep well away whilst filming. My second film was made on the north Norfolk coast which is used as a training and practice area for aircraft from East Anglian bases which you might hear in the background on the film. I once heard the RAF and USAF up there in those big Norfolk skies described as “mad blowlamps whanging around a Constable sky,” and such deafening noise from above can be a tad off-putting just as you try to say something significant. The process of demonstrating on film is hard work as one is very aware that the painting just has to work. No reruns are possible, so no pressure there then?

RR: I now have mauve on my palette and it has become a staple for my skies. Your palette is a bit different than many United States plein air painters. Can you list your favorite colors?

CD: My colour is subjective, but it naturally tends to the cool side, which I think might be a European thing. In other words, we can’t escape our heritage of mists and mellow fruitfulness. I know when I worked with [a group of American painters], they said my colour was ‘very English.’ I smiled, said ‘thank you,’ and carried on not quite knowing what they meant, but they’re right; your colour is different, beautifully ‘scientific’ and a clearer and cleaner palette perhaps due to less water vapour in the atmosphere over your side. I know I use very little actual paint and I have no complicated theories about colour or magic formulae. I do know, however, that if you took away my French ultramarine, my black and lemon yellow that makes my green, my Naples yellow, raw umber to calm things down, and my permanent mauve and light red, I would be lost. All the others, such as viridian, cerulean blue, cadmium yellow, orange and violet, I use to spice up the others. I only use Old Holland white, number two mixed, on Skip Whitcomb’s advice. He’s right – it is the best. If I remember, I ‘dry out’ the colour on newsprint the night before going out. The newsprint absorbs the excess oil to leave a drier textured paint, which I prefer. I never dilute colour with a solvent, and I never use mineral spirits indoors, always a non-toxic product like Zest-It.

RR: When I watched the DVDs, one comment was really appreciated. You said (and I am paraphrasing), “I don’t really know what is going to happen,” and to me that was the ultimate statement of honesty. You do take chances when you paint, don’t you?

CD: Taking chances, thereby hangs the tale! You could look at a thousand examples from the history of the expressive arts and their success would be due in part at least to the artist leaping into the dark and taking risks with the medium, be it words, movements, sounds or colours. Suffice it to say, go ahead and try it, the noble gesture. What I do know is that risk taking is the only way to achieve the ‘happy accident,’ be it a bold mark with a larger brush, areas wiped out with a cloth, or scraped out with a knife to leave a ‘ghost’ of the original, leaving fertile ground for working into the painting again. Having done all that, the trick is to recognize what has ‘worked’ and save it, and not be tempted to overwork the thing. I often confront a subject and wonder how on earth I’m going to make anything of it, or even how to start. I like and value that insecurity, which protects me from the formulaic and the ‘this is always how I do it’ school of thought. The downside of that thinking is that it can take some time to get a painting going on a track that excites me, and I won’t pursue it until it does. There has to be the initial spark of excitement to ignite the whole. I will battle with the first stage until I see that spark of enlightenment! I need the embryonic painting to talk back to me and not remain silent. I must have a dialogue with the thing. I need the board to wake up and argue with me. When that starts to happen, then we are in business. I think also it’s wise not to jump into a painting too fast. I stand and look at my subject until I can decide exactly what interests me about it, and make the painting about that, rather than blandly painting everything just because it’s there. The question is what the painting is about, not what this painting is of.