Questions & Artists: Hal Prize Judge Wing Young Huie

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

When Wing Young Huie was a 20-year-old journalism student at the University of Minnesota, he bought his first camera. Like any budding photographer, he “didn’t even know how to think about photography.” So once he earned his journalism degree, he took a class.

Under the watch of Bronx street photographer Garry Winogrand, best known for his portrayal of mid-20th century American life and social issues, Huie learned how to think like a street photographer. He kept his budding passion on the side while pursuing a freelance journalism career, eventually trading his pen for a camera and becoming a freelance commercial photographer as well as a photojournalist for several Minnesota publications.

His push into the street photography world came in 1995 when he received a grant for his first major project: a two-year assignment shooting photos of residents of Frogtown, one of the oldest neighborhoods in St. Paul and home to the largest Hmong community in Minnesota. These photos captured residents going about their everyday lives – hanging out on porches, playing basketball, having a family meal and praying in church.

The photos would find their way into a groundbreaking outdoor installation in the neighborhood, an artistic display of the social, economic and cultural realities of its people.

“Hai, Owner of Tip Top Haircut, South Minneapolis, MN,” part of Huie’s “We Are the Other” project.

In the two decades since, Huie has continued to push the boundaries of street photography, using his camera to capture the everyday lives of thousands of citizens while exploring a variety of social issues: immigration, race, adoption, urban and rural life, dementia, faith, gender, homelessness and youth culture.

Public exhibitions have become Huie’s means of sharing his photos with the world. In the late 90s, Huie moved into a low-rent area of a neighborhood along Lake Street in Minneapolis and spent four years photographing its residents. In 2000, he spent a month installing 675 photographs from the project in windows, bus stops (and buses), and on the side of the former Sears building to create a six-mile-long “Lake Street USA” photo exhibition that reflected the area’s economic and cultural realities.

A decade later, he repeated the process, this time collaborating with Public Art Saint Paul to transform University Avenue into a six-mile-long gallery of 500 photos taken of St. Paul neighborhoods over the course of three years.

For the past five years, Huie has been the lead artist of the artist-run Third Place Gallery in Minneapolis, which serves as an extension of his public art installations and a place for artists to connect. His current photo project is “Chinese-ness,” a documentary, meta-memoir, and actual memoir in one, exploring Huie’s identity as the youngest of six children and the only one in his family not born in Guangdong, China.

“Cheng and Wing, Guangzhou Railroad Station, (I am You), Guangzhou, China,” part of Huie’s “Chinese-ness” project.

The series was inspired by his first visit to China, in 2010, and addresses Huie’s “what ifs?” in life – “what if I had not gone to college and ended up owning a Chinese restaurant like my father or ended up becoming an engineer like my brother or ended up turning out the way my mother wanted me to turn out, marry a Chinese woman and have Chinese kids? So I decided to photograph Chinese men whose lives I could have had and then I give them the camera and ask to wear their clothes and they photograph me as them. Then I put the photographs together.”

The start of “Chinese-ness,” as well as Huie’s other photography projects from the past three decades can be viewed on his website, WingYoungHuie.com.

This year, Huie will serve as the photography judge for the Peninsula Pulse’s Hal Prize contest. The Pulse caught up with Huie to talk about his street photography, approaching strangers for photos, and what makes a good picture.

Alyssa Skiba (AS): Were you always comfortable shooting photos of strangers?

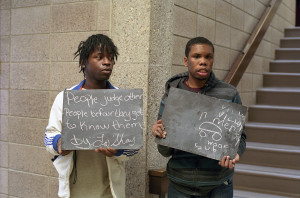

“Students at Transitions Plus, South Minneapolis, MN,” part of Huie’s “We Are the Other” project, which encouraged connection between neighbors who didn’t know each other well or at all.

Wing Young Huie (WYH): I’m probably more uncomfortable photographing people I know (laughs). It’s my way of getting outside of my own bubble; just like anybody, my bubble is personal, it’s cultural, it’s technological, it’s socioeconomic but in my private life, I wouldn’t approach thousands of strangers but this is what I do when I have a camera around my neck … I think that it’s exhilarating to approach someone and enter their reality and come away with a photograph, especially if you think that person is different than you. So photographing thousands of strangers, each interaction becomes part of my human experience. It’s my way of normalizing the world. I do see that my personal life and my professional life are intertwined to the point that you just look at people as people.

AS: What is your photographic process?

WYH: Very simple. I just walk up to people, I say I’m a professional photographer, I’m an artist, I’m doing this project for “x” reason, I’m photographing your neighborhood, I’m going to have a public exhibition … it’s that simple. A lot of people say no and I never try to talk people into being photographed. What are all the reasons why people say yes? Who knows? … I think just being paid attention to and having someone photograph you, it’s a different kind of experience. I think people feel honored, they feel respected, and basically I hang out. I think of it as a collaboration; it’s kind of a dance – sometimes I’m leading, sometimes you’re leading. It’s interesting where it goes. It’s really kind of reacting with life, see what happens, and maybe you’ll get a good photograph out of it. Once I started thinking of it as a collaboration, it became a little different. I think that the thing about documentary photography, no matter the intention of the photographer, often the people become exoticized and objectified and so how do you take a photograph where the person in the photograph, the person who took the photograph, and the person looking at the photograph have equal agency? That’s not easy to do but in a way that’s my goal.

AS: You are going to be judging the photography portion of the Hal Prize. What advice would give to participating photographers?

“Kirby at Cup Foods, South Minneapolis, MN,” part of Huie’s “We Are the Other” project.

WYH: My advice is, if you look through the lens and you’ve seen that picture before, try to do something different. What is a good photograph? Certainly it’s all subjective. I have my ideas. It’s not so much about how well the photograph was taken, it’s why you took it. What you decide to photograph is more important than how you photograph it. I never talk about composition, I never talk about rule of thirds. Everyone has different points of view but how do you get at life in a photograph? How do you make something real? That’s not easy to do. That doesn’t mean you can’t set it up – you can still set something up and it can look real, authentic. There are movies, there are famous actors, a director, lighting, a crew but there are moments that you forget that it’s a movie. It suspends disbelief, so how do you take a photograph like that? That’s what you should think about. It’s art. Some people think it’s composition, rule of thirds, repetition. I don’t think about any of those things.