Redefining Wisconsin Shorelines

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Proposed legislation would bring clarity to a murky process, advocates say. Opponents say the legislation is a constitutional violation of Wisconsin’s Public Trust Doctrine.

Legislation passed to Gov. Tony Evers by voice vote would change the way shorelines are defined. Evers had not made a move on either signing or vetoing the legislation as of this week’s Peninsula Pulse deadline, but if he does veto it, it’s not likely to slip quietly away.

“This bill has been years in the making, including contributions from other colleagues in prior sessions who worked on it before stakeholders brought it to my attention last year,” said the bill’s author, Sen. Duey Stroebel (R-Cedarburg), during the committee hearing last month for Senate Bill 900.

The stakeholders Stroebel referred to – all of whom support the legislation – include the League of Wisconsin Municipalities, Wisconsin Realtors Association, NAIOP Commercial Real Estate Development Wisconsin, Wisconsin Economic Development Association, Wisconsin Land Title Association and virtually all shoreline cities within Wisconsin, regardless of political affiliation, including Ashland, Bayfield, Manitowoc, Marinette, Milwaukee, Oshkosh, Sheboygan, Sturgeon Bay and Superior.

“Great Lakes coastal communities need this legislation to make it possible to develop dilapidated or underutilized waterfront property that hasn’t been submerged for half a century,” said Toni Herkert, government affairs director for the League of Wisconsin Municipalities, which represents some 600 municipalities across the state.

If the Land Is No Longer Shoreline, Why Shouldn’t It Be Developed?

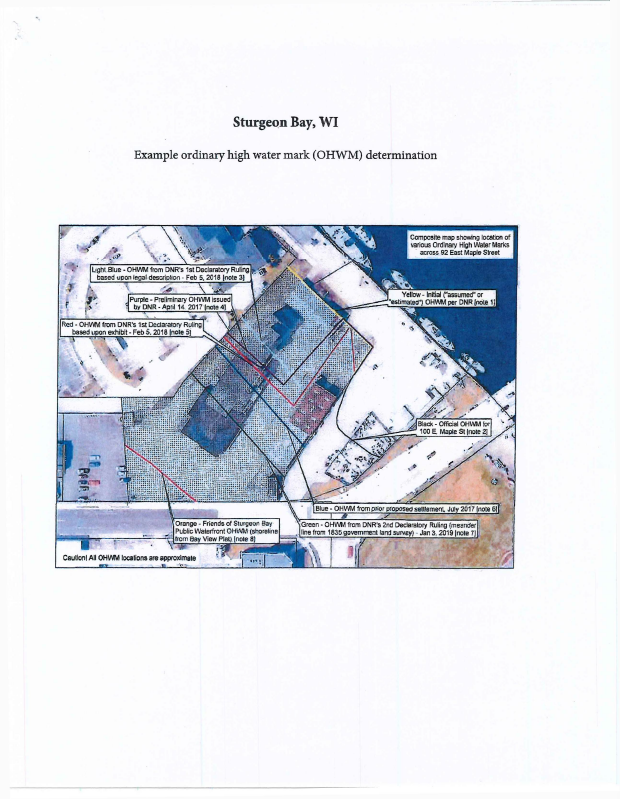

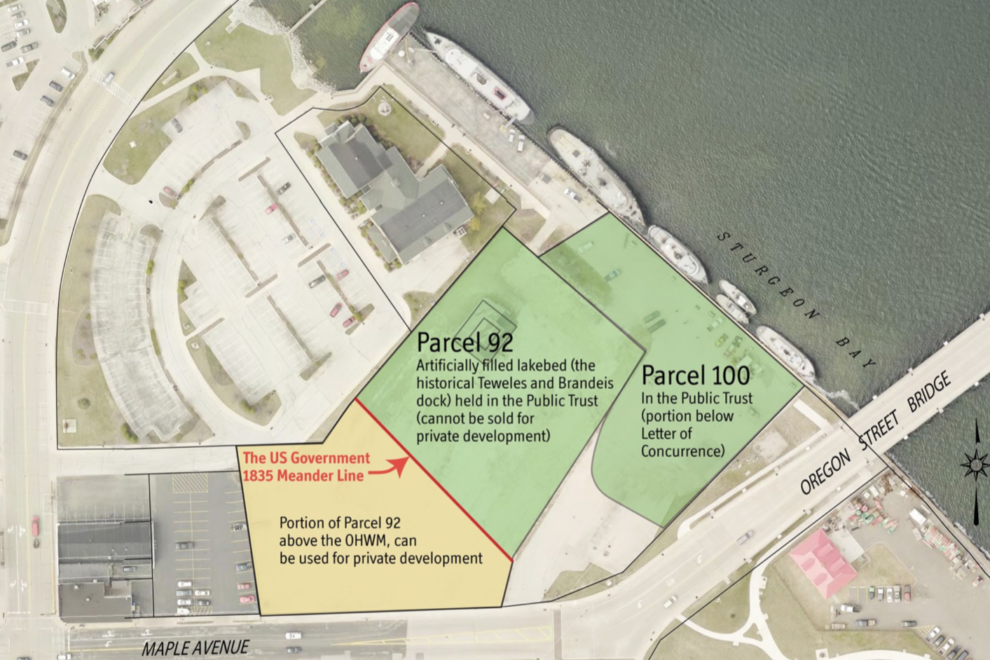

The legislation applies to land that’s below the ordinary high water mark (OHWM): the point on the bank or shore where the water and its action meet the land. The OHWM is important because under Wisconsin’s Constitution, it’s the line that establishes the geographical boundary of Wisconsin’s Public Trust Doctrine, which gives the public the right to access and enjoy Wisconsin’s navigable waters.

This doctrine applies with equal force even if the shoreline has changed due to natural and human causes and the land below the OHWM has been dry and filled for decades. The legislation, then, according to its supporters, would provide clarity on whether landowners may use or build on those lands that were filled prior to Dec. 9, 1977. (After that date, the state required a permit for permanent alterations, deposits or structures along navigable waters.) Without that clarity, supporters say, shoreline development is too risky.

“When an issue as great as ‘Where is the shoreline?’ comes up and there isn’t any certainty, the shoreline can’t be defined reliably or predictably – that breeds uncertainty and a disincentive for revitalization,” said Josh VanLieshout, Sturgeon Bay city administrator. “The stakes are so high you can’t really go into it without knowing as much as you can and what rights are where.”

The legislation lays out a process for changing the OHWM. If a title owner could prove a section of land was upland since Dec. 9, 1977, the individual could apply to the municipality for a proposed shoreline. If the municipality determined the proposed use would promote the interests of the public and still allow public access, the proposed shoreline would be subject to review by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR). The DNR would then hold a public-notice and comment period. If approved, the new boundary of title between land held in trust by the state and land held in fee title ownership would be established.

If this process came to pass, Sheboygan’s mayor estimated the city would gain an estimated $50 million in taxable income.

“This [legislation] is vital to the growth and success of our community,” said Sheboygan Mayor Ryan Sorenson during last month’s committee hearings on the legislation.

Legislation Would Allow an Unconstitutional Land Grab

Currently, the DNR enforces the state’s constitutional responsibility to oversee and manage the uses of public trust lands, including lake beds that have been filled.

“And they cannot give that up to a local unit of government, and it cannot give those lands to private owners,” said Fred Clark, executive director of Green Fire Wisconsin. “This [legislation] does both of those things.”

Green Fire Wisconsin is one of several environmental organizations – including Clean Wisconsin, Midwest Environmental Advocates, Sierra Club-Wisconsin and Wisconsin Conservation Voters – that oppose the legislation.

“In essence, the legislation is broadly drafted such that it would allow municipalities to redraw the shoreline and the boundary between public trust land and private property in ways that are wholly inconsistent with the Wisconsin State Constitution,” said Tony Wilkin Gilbert, executive director of Midwest Environmental Advocates.

The legislation would require the DNR to approve the municipality’s request, but Gilbert argued that approval would amount to a rubber stamp when to do otherwise would open the agency to lawsuits.

“So it was drafted to give the DNR a role, but not a meaningful role, and it’s not its constitutionally adopted role,” Gilbert said.

Residents also voiced their opposition to the legislation in writing for the legislative hearings. All of them were from Door County: Morgan Rusnak, Cathy Grier, Shawn Fairchild, Nancy Aten, Chelsea and Paul Anschutz, Laurel Duffin Hauser, Katie Baeten and Dan Collins.

The issue is near and dear to them. This is not just because Door County has arguably more at stake than any other Wisconsin community, given the nearly 300 miles of shoreline that hugs its shore, but because it’s been only a few years since a group of residents successfully invoked the Public Trust Doctrine to save Sturgeon Bay’s West Waterfront from a hotel development.

“The legislature cannot just create a law that makes new boundaries that create a title for a public trust property, so that now it can be transferred into private hands,” said Sturgeon Bay resident Shawn Fairchild, a member of the Friends of Sturgeon Bay Public Waterfront, in written testimony for the committee hearings. “That is exactly what was tried in Sturgeon Bay by the local municipality, and it failed miserably in court.”

That court action involved the Friends’ petition of the DNR for a ruling on the West Waterfront’s OHWM after the city proposed a hotel for the site. It became a years-long fight before the DNR finally decided in favor of the Friends group.

Having fought and won that battle to preserve the waterfront and the constitutional right for the public’s access to it, the proposed legislation is like a punch to the stomach for the Friends group members.

“This bill would directly enable municipalities, when cash strapped, on a whim or under pressure from powerful groups, to remove public trust lands on filled lake beds, owned by the state for the people of Wisconsin, and sell for private commercial development,” said Nancy Aten, a Sturgeon Bay resident and member of the Friends group, in an email to the Peninsula Pulse.

Sturgeon Bay’s VanLieshout and Marty Olejniczak, the city’s community development director, testified in Madison on behalf of the legislation at both the Senate and Assembly committee hearings. They said they wanted to protect other cities from going through what Sturgeon Bay did when the city agreed to sell the land to the hotel developer, only to learn that the land was historic lake bed and couldn’t, by virtue of the Wisconsin Constitution, be sold for private benefit.

“My testimony was not intended to undo that situation, but rather was to prevent that long, expensive and divisive process from happening again elsewhere in Sturgeon Bay or in other Great Lakes municipalities,” Olejniczak said.

Neither would the legislation apply to the West Waterfront land, which is already under a submerged land lease and exempt from the legislation, Olejniczak said.

“Fortunately, we’re mostly done,” VanLieshout said. “I don’t think there’s a lot more redevelopment along the waterfront that could happen.”

Ultimately, the final OHWM on the West Waterfront was negotiated between the Friends and the city and then ratified by the DNR. The legislation, in practice, would not be much different from that, Olejniczak said.

“The difference is it’s not necessarily an adversarial process to start,” he said.

Clarity Is Needed, but Not This Way

In its written testimony during the committee hearings, the DNR said it could support legislation that cleared up title and allowed development, but the agency stopped short of endorsing the legislation as it had been drafted and suggested amendments to the version of the legislation it reviewed.

“The goal could be to devise a way to meet the Public Trust Doctrine requirements by balancing some loss of the public values in the historic lake bed or riverbed, with the allowance of some private development, and including real increases in public use of the coastline,” the DNR wrote.

Green Fire Wisconsin’s Clark concedes that former lake bed lands are complex, and there’s room to improve the process for determining what may and may not be done on landlocked parcels that have been nowhere near a shoreline for decades. But not with the legislation that’s on the governor’s desk.

“This opens the gates wide to anyone who wants to use public trust lands for private interests,” he said.

Both of Door County’s state legislators support the legislation. Rep. Joel Kitchens (R-Sturgeon Bay) passed the legislation’s Assembly version out of the Assembly’s Environmental Committee, which he chairs.

“Sturgeon Bay was the sort of worst-case scenario,” Kitchens said. “Nobody looking at this wants to be Sturgeon Bay.”

Sen. André Jacque (R-De Pere) cosponsored the Senate bill. He said it would bring “legal clarity to land ownership so local communities can make decisions about land use as well as improve contaminated or blighted land along the shoreline.”

But Midwest Environmental Advocates’ Gilbert sees a bill that’s poorly and broadly drafted and clears up nothing.

“The advocates say their goal is to create legal certainty for those who purport to own public trust land,” Gilbert said, “but if the bill were to go through, it would invite litigation.”

Perhaps that’s what’s needed, Kitchens said.

“It will very likely be challenged in court,” Kitchens said. “I welcome that. We kind of need that so we can decide once and for all.”