Remarkable Life of Thordarson Unfolds in New Purinton Book

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

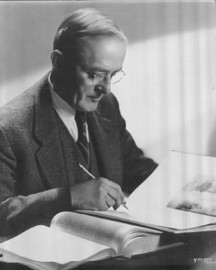

Thordarson, the subject of Purinton’s new book, owned almost the entirety of Rock Island in 1912. Photo courtesy the Washington Island Archives.

Rock Island, a state park since 1965, is not the easiest place to visit. Two ferry rides are required, and no wheeled vehicles – not even bicycles – are permitted on the island. It has no electrical service, no provisions are sold there, its 42 campsites offer only pit toilets, picnic tables, and fire rings. Five of the sites require a hike of more than a mile from the ferry dock.

Yet, the island attracts more than 25,000 visitors a year. Many of them, it can be assumed, go there specifically to see C. H. Thordarson’s magnificent boathouse. Even for those who know it is there, the first glimpse of the magnificent stone structure, rising 65 feet above the water, must be awe-inspiring. For those who stumble onto the sight unaware, it must seem as if it were dropped in place from another world – which, in a way, it was.

If most people know little about the origin of the boathouse, even fewer are familiar with the life of Chester Hjörtur Thordarson, the man whose dream it was. Thordarson and Rock Island, a just-published book by Richard Purinton, brings the Iceland-born millionaire inventor to life, primarily through his correspondence. Amazingly, Purinton’s book is the first about Thordarson to be printed in English.

Hjörtur Thordarson was born in Iceland in 1867. When he was six, his family immigrated to Milwaukee. They were part of the massive exodus – nearly 20 percent of Iceland’s population – who were motivated by hard economic times to make a new start in the United States during the late 19th century.

Unfortunately for the Thordarsons, the father died within months of their arrival in Wisconsin. To be close to other Icelandic immigrants, the family moved often before finally settling in 1881 on a farm in the Red River Valley of North Dakota. They could afford train tickets only for the women and small children. Hjörtur, by then 13, walked barefoot for two and a half months to cover the thousand miles to their new home. His formal education had ended with second grade.

At 18, he joined two older sisters in Chicago and, determined to further his education, enrolled in fourth grade. By 20, he’d finished seventh grade and secured a job with an electrical manufacturing business. From his $4 weekly pay, he paid $2 for room and breakfast and $1 for other meals. The remaining $1 was set aside to buy books, especially those related to his passion for science.

In 1894, with $75 to his name – he was now going by Chester, a name suggested by one of his first teachers, or C. H. Thordarson – he started his own business, Thordarson Electric Company, and married Juliana Fridricksdottir, also a native of Iceland, whose parents had settled on Washington Island. The owner of an exclusive dress shop in Chicago whose customers included Mrs. Marshall Field and members of the family that owned the Palmer House, Juliana was eight years older than her husband. Their sons, Duí (Dewey) and Tryggvi (Trig) were born in 1897 and 1903.

Thordarson was an astute, hard-nosed businessman, always fair to others, but also always alert to being taken advantage of. A brilliant, mostly-self-taught scientist and inventor, he eventually held hundreds of patents.

In 1910, he became interested in buying land for a retreat on Washington Island. When the desired plot proved to be unavailable, he turned to 900-acre Rock Island. By 1912, he owned the entire island except for some 130 acres that included the lighthouse built in 1836, the first in Wisconsin. The acreage Thordarson purchased included several homes that had been deserted decades earlier. Some were demolished and others, including the one that became the family vacation home, were restored and enlarged.

As his electric company flourished, Thordarson’s social circle had widened to include people like Chicago Mayor William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson, whom he gifted “for life” with a log cabin, Eugene F. McDonald, president of the Zenith Radio Corporation, and other prominent politicians and members of the Chicago Yacht Club. Other luminaries, including Clarence Darrow, were also guests on the island. Thomas Edison was a good friend. (There were rumors that Al Capone, who was thought to have some association with Mayor Thompson, may have used the island for staging illegal liquor from Canada during Prohibition, but that can probably be chalked up to Door County’s love for a good scandal.)

Workers rest when the boathouse was near completion, circa 1929 or 1930. Photo courtesy the Washington Island Archives.

Thordarson was interested in preserving the plant and animal life on Rock Island and also experimented with “electrical agriculture,” using airborne electricity to enhance the growth of plants in shaded areas.

Construction of the 70’ x 40’ multi-level boathouse began in the fall of 1925 and took about five years to complete. Although always busy with business in Chicago, Thordarson served as general contractor for the project and oversaw every detail of the work. Some of the materials were purchased from J. F. Bertschinger of Egg Harbor, who noted in a 1928 letter that his Alpine Resort was about ready to open.

Along with his passion for creating a private getaway – perhaps reminiscent of the quieter life he remembered from his early childhood in Iceland – Thordarson never lost his passion for books.

His collection totaled about 11,000, many of them rare and extremely valuable. Many were sent to England to be rebound.

Thordarson was a successful businessman, a brilliant inventor and a friend of the famous. But his relationship with his family was less successful. He and Juliana were estranged for many years. (Granddaughter Julie Ann Thordarson McGuire reported that when a great peal of thunder interrupted Juliana’s funeral in 1955, Dewey whispered to Trig, “Mother must have met father!”)

Thordarson insisted that Dewey change the date of his wedding to one of his father’s factory employees so that it would take place on Thordarson’s birthday, and he planned every aspect of the ceremony. Trig’s wife reported that they moved from Chicago to Florida when their baby was expected, because they believed that Thordarson “would orchestrate the whole thing in the delivery room.” They named the little girl Julie Ann in honor of her grandmother, over Thordarson’s objections.

The Depression years were difficult for Thordarson Electric, which eventually was taken over by the Burgess Company. Ill health, both mental and physical, plagued Thordarson in later years, and – coupled with financial difficulties – halted building on Rock Island, but he continued to tinker with engines in the machine shed.

Thordarson died in 1945 at age 77. Strangely, the metal container holding his ashes was left behind in the boathouse as family members sailed away from the island after the property was sold to the state in 1965. When someone noticed it and called to those on the boat that they’d forgotten something, the response was, “Keep it. It’s yours.”

Purinton read from his new book at the recent Washington Island Literary Festival, in the Thordarson Boathouse on Rock Island. “An exceptional occasion and rare privilege!” wrote Purinton about the experience. Photo courtesy Island Bayou Press.

Thordarson’s papers went to the Wisconsin State Archives. The University of Wisconsin-Madison originally offered $300,000 for his book collection, but the family finally received just $170,000. The collection included four Audubon folios. In 2000, a folio from another source sold for $8.8 million.

Chester Hjörtur Thordarson was a complex man. Richard Purinton has obviously done careful research to allow Thordarson’s extensive business and limited personal life to unfold through his own correspondence and Purinton’s thoughtful commentary. This is the third book by the president of the Washington Island Ferry Line. The first, Words on Water, A Ferryman’s Journal, was begun at the suggestion of the late Norb Blei and was based on Purinton’s daily musings in 2007. The second, Bridges Are Still News, a collection of island essays, poems and photos, was published in 2010.

If you think it unusual that a ferryman should also be an accomplished writer, consider that Purinton has a journalism degree from the University of Wisconsin – Madison. He grew up in Sturgeon Bay and married his childhood friend, Mary Jo, was father was Arni Richter, founder of the Washington Island Ferry Line. Purinton learned the business the old-fashioned way, starting as a deck hand.

Greco Gallery of Sturgeon Bay will host a book signing by Purinton on Nov. 16 from 1 – 3 pm.

Purinton’s books can be found in Sturgeon Bay at the Door County Maritime Museum gift shop, Untitled Books and Book World; in Baileys Harbor at Novel Ideas; in Sister Bay at Al Johnson’s Butik; and at the Washington Island Ferry terminal on the island.

For more information or to order books, call 920.847.2546 or visitwisferry.com.