Park Removes Deteriorating Memorial Pole, Sparking Questions About Its History

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

“What the Door County Historical Society, the state historical society, and the Wisconsin Conservation Commission say may someday be forgotten. But may our acts and our deeds be an incentive to those who came after us to show their devotion to their worthy fellows.”

— C.E. Boughten, a newspaper editor from Sheboygan who admired Kahquados and helped pay for his funeral expenses.

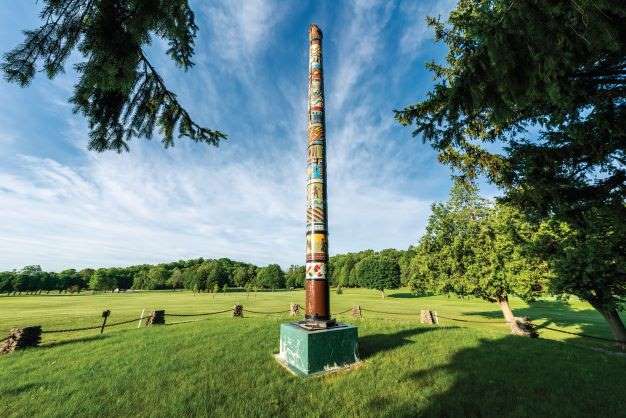

To the left of the ninth fairway at Peninsula State Park Golf Course, a pocket now sits empty at the center of a small band of cedars and a circle of stones. For 91 years, the pocket was filled by a pole. Some called it a totem pole, others a memorial or a column. Still others saw it as a misguided acknowledgment of a people displaced.

In June, the pole came down quietly, with no announcement, fanfare or ceremony. It was first constructed in 1927 to honor the Potawatomi, who lived in parts of northern Door County and Washington Island for centuries before the arrival of white settlers. In 1931, Potawatomi Chief Simon Onanguisse Kahquados, was buried near the base of the pole.

The wear and tear on the 37-foot-tall pole from weather, errant golf balls and birds began creating a safety hazard three years ago.

“There were several spots where you could see straight through to the steel pole in the middle of the post and rotting at the base,” said Eric Hyde, superintendent of Peninsula State Park. The bear that sat atop the pole was also severely damaged.

Some people wanted to have the pole replaced, but the Department of Natural Resources consulted with the Forest County Potawatomi first.

Hyde said those conversations were initiated several years ago, but COVID-19 delayed action. Conversations resumed this spring when Hyde; Jason Daubner, Peninsula State Park Golf Course general manager; and Jennifer Birkholz, Peninsula State Park assistant superintendent, met with Benjamin Rhodd, Richard Brzezinski and Donald Keeble of the Forest County Potawatomi to discuss the future of the pole.

“We discussed what the bands meant and the rings, and they told us the pole doesn’t mean anything to the tribe, and that totem poles are not part of their culture,” Hyde said, which Rhodd confirmed.

“We’re not sure why in 1927 this was erected,” Rhodd said. “We have seen some articles that referred to Chief Simon liking totem poles,” but Rhodd said he doesn’t know why it was chosen as an icon of native representation for his tribe. The Menominee also don’t have a tradition of totem poles, despite the pole’s band that honors that tribe. It was added by Chief Roy Oshkosh of the Menominee Tribe when the pole was replaced in 1970.

Hyde said that knowledge made it an easy decision to take the pole down. Rhodd said the tribe’s greater concern is protecting Chief Kahquados’ burial site from golf carts driving over it or hitting balls on it.

The park now plans to work with Rhodd to come up with an interpretive display or other recognition of the land’s history at the golf course’s clubhouse.

Pole Significant for Man Buried There

The authenticity of the totem pole as a cultural symbol of the Potawatomi was a concern even at the first suggestion of the pole. Door County historian Hjalmar Holand, as president of the Door County Historical Society, directed the creation of the pole and designed its features.

“The only kind of monument the ancient Indians knew was the totem pole,” Holand wrote in the September 1927 Peninsula Historical Review, lumping all tribes together.

He disputed the idea that poles were never used by Midwestern tribes and adopted the idea of the totem pole to symbolize tribal history.

But even for a totem pole, Holand’s design was problematic.

Holand wrote that the panels on the pole “represent outstanding events or periods in the history of the tribe,” but only one band represents all of Potawatomi history prior to the white man’s arrival. The rest of the bands represent events after the arrival of the white man – trade, the arrival of missionaries, the French and Indian War, and finally, a nod to the Potawatomi being driven from their possessions with the coming of white settlers.

Those scenes were interspersed with illustrations of Potawatomi art designs. The bear sitting atop the pole was intended to represent the principal clan of the Potawatomi.

But even if the pole is not culturally significant to the tribe, it was significant to the man who is buried there.

The pole was dedicated Aug. 14, 1927, during an elaborate program attended by 32 Potawatomi and a crowd estimated at more than 6,000 people. It was there that Chief Kahquados gave remarks and pulled the cord to remove the muslin wrap, unveiling the pole.

“We have never looked for any honor from the white people, and we have not received any,” Chief Kahquados said, according to reported accounts of his speech. “We are therefore grateful that there are men who look with respect upon our fathers and have raised this pole as a visible sign.”

Kahquados then sang “America the Beautiful.”

So honored was Kahquados that he gave Holand a Potawatomi name, Kayagegiskong, to adopt him into the tribe, and Kahquados stated his desire to be buried in the park.

“It is my wish, and I hereby direct that I be buried in the Wisconsin state park at Ephraim, Wisconsin, according to my previous arrangements with the Door County Historical Society,” Kahquados wrote in his last will and testament, dated July 30, 1930.

Early Form of Land Acknowledgment

Colleen Bins, an Oneida and owner of Chief Oshkosh Trading Post in Egg Harbor, said the pole’s history is complicated. Despite the fact that the pole is not authentic to Potawatomi culture, she said Kahquados and Chief Roy Oshkosh of the Menominee may have been playing a part that people wanted them to play in hopes of some form of acknowledgment. “Totem poles are not a part of Oneida culture either,” she said, “but I have them in front of my house. That totem pole may be the only reason we’re talking about this history today.”

It is common now for organizations, businesses and governmental bodies to make official land acknowledgments to recognize the people who came before them. The pole could be seen as an early, prominent form of this.

The unveiling of the pole in 1927, and the burial of Chief Kahquados in 1931, were both front-page news in the Door County Advocate for several months leading up to the events. Kahquados returned to visit Door County from his home in Blackwell, Wisconsin, several times during the years following the unveiling, and his visits were often front-page news, as was his death on Nov. 22, 1930.

When he was interred beneath a nine-ton boulder near the pole on Memorial Day 1931, the ceremony was attended by a crowd estimated at more than 10,000 people.

“This stone marks the grave of Simon Onanguisse Kahquados, head chief of the Potawatomi Indians,” reads the marker on the stone. “He was the last descendent of a line of chiefs who ruled over the Door County Peninsula for many centuries. He was born May 18, 1851, and died Nov. 22, 1930. A fine and worthy Indian. This memorial has been erected by the Door County Historical Society.”

The chief’s grave marker was unveiled by James Wampum, secondary chief of the Potawatomi tribe and one of the pall bearers who escorted the casket to the site. The Sturgeon Bay High School band played music, and remarks were made by Holand, Jens Jensen, Joseph Schafer, superintendent of the state historical society, A.W. Icks of the Wisconsin Conservation Commission, and Congressman George Schneider, who persuaded Congress to appropriate $100 for the burial.

A Strange Paradox

Photos and home videos of the funeral on Memorial Day weekend show the grounds of the course filled with people and cars in all directions. Newspaper reports called it the largest gathering in the history of the peninsula. Some of those in attendance could have been children when Kahquados and his people were driven from their lands just a generation or two earlier.

“It is a strange paradox,” Rhodd said, “to see Simon having died early in the 20th century, and having such a large turnout at his funeral, by European-descendant peoples. It is kind of strange that there was such an honor for this man on that level by non-native peoples, government officials. It was a huge event. Why did so many come?”