Review: ‘The Summer Before the War’

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

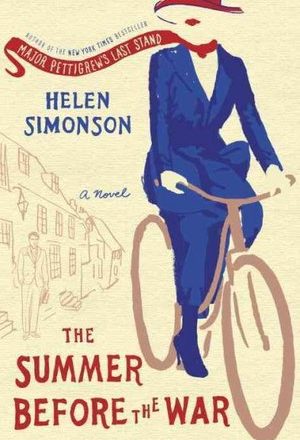

Helen Simonson followed the bestseller success of her 2010 debut novel Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand with a second book, The Summer Before the War. The British author had spent her teenage years in the East Sussex village of Rye, the setting for her novel which begins in 1914 during the summer before the beginning of the war that was touted as the one to end all wars.

The romantic idealism with which British society approached that conflict, the anticipation of short skirmishes that would bring peace and produce war heroes, soon became the grim reality of trench warfare and gas masks, field hospitals and the realization that churches were hosting far more funerals than weddings. And the celebration of the 1918 armistice was compromised by a flu pandemic.

The irony of World War I has provided fertile material for literature, beginning with the war poems of Rupert Brooke and Wilfred Owen, both soldiers who perished in the war, followed by Erich Maria Remarque’s classic All Quiet on the Western Front in 1929. The 1969 satiric musical film Oh! What a Lovely War offered a dark comedic look at that conflict.

Simonson’s carefully researched novel begins as a gentle story amid a backdrop of local citizenry making contributions toward the war effort with the recreational enthusiasm that might be expected of fundraisers for building a new school or constructing a city park for children.

The author not only recreates the ambiance of the time, the late Victorian concern for propriety, but does so in a prose style that mimics writers of that era.

Central to the story is Beatrice Nash, a young woman whose father has died leaving her alone to earn her keep. An aspiring writer and scholar, she has come to Rye to teach at an elementary school. Her advocate is an older woman Agatha Kent whose husband John is a senior official in the British Foreign Office. Childless themselves, the Kents have taken under their wings two nephews, idealistic medical student Hugh Grange and foppish poet Daniel Bookham.

The young people are caught up both in their budding careers – Beatrice’s trials as a new teacher, Hugh’s dreams of fame as a surgeon, and Daniel’s hopes of publishing a journal – and the frustrations accompanying the faltering course of true love – a suitor that Beatrice finds offensive, a fiancée that Hugh mistakenly idealizes, and a friend for whom Daniel inappropriately has a love that dares not say its name.

The initial village generosity in welcoming refugees from Belgium who have survived atrocities at the hands of invading Nazis is compromised by the unsettling realization that some of the outrages suffered could not politely be spoken of in public. People of substance are willing to open their homes to convalescing officers, but fear a breach in decorum at the suggestion that they take in enlisted men. Food shortages are also troubling, especially for those accustomed to living well.

And through it all, Simonson’s sense of humor emerges, often in subtle ways and sometimes the not-so-subtle when the outrageous irony of the prejudicial words and actions of some of the antagonists becomes darkly humorous.

During the first three-quarters of the novel, the workings of an early 20th century English village are gently engaging. But then the reader travels with Hugh, Daniel, and some of the other local men to the battlefields of France, and the tone shifts violently. And when some of them don’t return, and others come back physically and psychologically damaged, those at home find themselves changed as well.

Helen Simonson’s novel not only engages the reader with an entertaining narrative, but she reminds us once again of the underbelly of war, the horrifying aspects we are too quick to forget when the ideals of duty and honor and justice send us once again marching off to battle.

A young newspaper reporter of my acquaintance wrote a feature article a few years ago on the state of public war memorials that citizenry had constructed to honor the service of the soldiers they had sent into harm’s way. One small town memorial consisted of a WWI Doughboy statue with the engraved words, “Lest we forget.” The deteriorating figure had been vandalized and marked with graffiti, the grounds littered.

The Summer Before the War by Helen Simonson / 473 pages, Random House, 2016