Saving Our Shores: Gallagher Continues Save the Bay Initiative

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

“Dead zone” was an oft-used term by area media the summer of 2013 when scientists announced that Green Bay had developed hypoxia in an area approximately eight miles northeast of the city of Green Bay and extending more than 30 miles.

The bay, which represents seven percent of the surface area of Lake Michigan, receives 33 percent of the basin’s total nutrient load, which means decades of high-nutrient pollution leading to low oxygen, algae blooms and fish kills.

U.S. Representative Reid Ribble was at the start of his third and final term representing the 8th District in Congress when he convened a meeting to talk about the phosphorus problem that created the dead zone in Green Bay.

That first meeting of farmers, government agencies, conservation groups, academics, business people and others interested in the subject turned into Ribble’s Save the Bay initiative.

When Ribble announced he would not seek a fourth term, many wondered if the person elected to replace him would continue the Save the Bay effort.

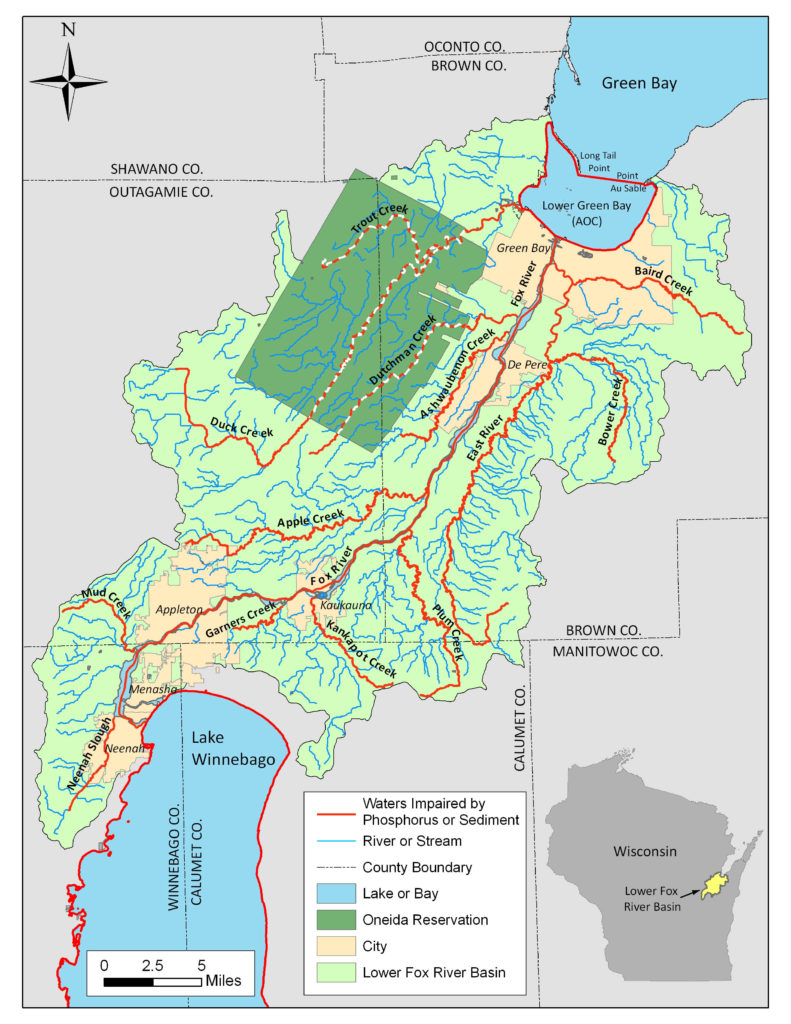

The Save the Bay initiative initially focused on the Lower Fox River Basin, where a high concentration of farms has contributed to runoff problems in Green Bay.

Mike Gallagher, the 33-year-old Republican who was elected to replace Ribble, said continuing the Save the Bay initiative was a no-brainer. In fact, Gallagher has a refreshing take on it.

“I consider myself a conservative and conservationist,” he said. “I’m a younger member of Congress. I often think one of the best ways to reach millennials, younger folks, is to talk about environmental issues, which may not be something that most Republicans are comfortable doing, but I think it’s something we need to do more of. Don’t force that false choice between our economy and our environment. I reject that choice. I think we can be environmentally friendly and economically strong at the same time.”

So Gallagher was well aware of the Save the Bay initiative, and he was impressed by the approach Ribble took.

“I was inspired by how Reid was able to bring together all these different stakeholders in Northeast Wisconsin,” Gallagher said. “If you are able to bring people to the table, I just believe that you are able to identify bottom-up solutions. Getting farmers and manufacturers to talk to academics and conservationists is a good thing. We need more of that bottom-up bipartisan problem solving rather than just fingerpointing. Hopefully Save the Bay can help other people to take this approach. How do we solve problems from the bottom-up rather than just talking past each other?”

Beyond that, Gallagher said he was encouraged by both farmers and conservationists to continue the initiative.

“I’m really excited about what we’re doing,” Gallagher said. “I do feel like we’re at a point now because of the conversation that was started by my predecessor and others, we are starting to identify some really innovative techniques. I think this is precisely the moment where we should be encouraging that and building on it. That isn’t to say we’re going to find a silver bullet solution to all of these problems. Maybe the solution that works for us in northeastern Wisconsin is different from some of the farmers down near Madison, but the more sharing of information and best practices, the better off we’ll be.”

Gallagher said he was happy with the turnout for his first Save the Bay meeting on February 21, 2017. It reminded him that a lot of talented, successful people are putting their minds and energy toward clean water efforts.

“I’d rather we be at the leading edge of it,” Gallagher said. “I see no reason why Northeast Wisconsin can’t end up being a world leader when it comes to some of these best practices, and if we do that right, that’s a really exciting future we’re looking at. We have some of the world’s best farmers. We live in one of the most beautiful places in the world. And we just have this Midwestern work ethic, sort of humble, hardworking ethos, and the spirit of civic duty and being a good neighbor. Those things combined should set us up for success in this area.”

We talked to some of the farmers who were called upon by Reid Ribble to save our shores. Here’s what they’re doing.

Dan Brick, Brickstead Dairy, Greenleaf

Dan Diederich, Diederich Farms LL, De Pere

John Jacobs, Green Valley Dairy, Krakow

***

Major Milestones in Phosphorus Pollution Reduction

1933

The federal government, along with desperate, but willing, landowners and farsighted bankers, launched the nation’s first watershed project in the mid-1930s to curb soil erosion in the 92,000-acre Coon Valley south of La Crosse and save the productivity of the soil.

1972

U.S. Congress passes the Water Pollution Control Act, which makes it illegal to discharge pollutants without permits and establishes two goals: make the nation’s waters fishable and swimmable by 1983 and eliminate discharges to waterways. Wisconsin in 1983 became the first state to meet the “fishable and swimmable” goals. Congress has failed to reauthorize the Clean Water Act since 1987.

Mid 1970s

Consistent with the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, municipal and industrial dischargers of phosphorus in the Great Lakes Basin are required to reduce their discharges to 1 milligram per liter.

1977

A program is created to protect Wisconsin waters from runoff pollution by offering to share costs with landowners and communities that take steps to keep soil, fertilizer, street debris and construction site dirt from washing into streams and lakes.

1984

Wisconsin starts requiring farms with at least 1,000 animal units, equal to 700 milking cows, 1,000 beef steers or 55,000 turkeys, to get water quality permits detailing the manure storage, spreading and other practices they must follow to reduce the risk of manure spills or runoff to lakes and streams since these operations produce at least as much organic pollution as a city of 18,000 people and spread it on fields, often without treatment.

1992

Municipal and industrial dischargers of phosphorus statewide are required to meet a technology-based limit of 1 milligram per liter of phosphorus.

2002

Wisconsin passes the nation’s most complete rules to cut polluted runoff from farms, urban areas, construction sites and roads.

2007

Changes to rules governing the state’s largest livestock operations, operations known as Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, go into effect to reduce phosphorus and other nutrients entering lakes and streams. Key provisions prohibit spreading liquid manure on frozen or snow-covered ground with limited exceptions and ban spreading solid manure on frozen or snow-covered ground during February and March unless it’s immediately incorporated.

2010

April 1, 2010, fertilizer that is labeled as containing phosphorus or available phosphate cannot be applied to lawns or turf in Wisconsin unless the fertilizer application qualifies under certain exemptions.

Beginning June 1, 2010, it’s illegal to sell or use household dishwasher detergent with more than .5 percent phosphorus by weight. The law ends an exemption for dishwater detergent to a 1970s rule limiting phosphorus in cleaning products.

Rules setting phosphorus water quality standards criteria and rule changes aimed at reducing phosphorus in wastewater discharges from industrial and municipal wastewater dischargers take effect December 1, 2010. Rule changes aimed at reducing phosphorus in runoff from farms take effect January 1, 2011.

Wisconsin releases reports that set pollution reduction goals for phosphorus and sediment for several major waters including the Rock River and tributary streams and the Lower Fox River and Green Bay. The federal government requires that the phosphorus budgets, known as Total Maximum Daily Loads, be developed for lakes and rivers with impaired water quality, and then implementation plans be developed to meet the phosphorus reduction goals.

Source: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources