Second Act

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

This article is the second of two parts about the life of Ephraim’s Herbi Hardt. If you missed part 1, read it here.

In 1939, serious throat surgery forced Herbi Hardt to leave his job at the Old Heidelberg in Chicago. He could no longer sing for an entire evening, but he was able to do a song or two at a retirement party for one of his wife Emily’s teacher friends.

The owner of the Cape Cod Inn in Des Plaines, Ill., where the party was held, was so impressed that he offered a partnership to Hardt, who eventually became the sole owner. But WW II loomed, and Hardt knew he’d be drafted. His wife and his mother wouldn’t be able to carry on his work at the inn, so he sold it.

“Having experienced all the chaos, misery, agony and sorrow of WW I, I could not imagine having to kill my own relatives,” says Hardt, who had emigrated to the United States from Germany in 1923. He registered as a conscientious objector and became a test driver of tanks manufactured by Henry Ford. He then became an inspector for sub chasers at the Pullman Shipyard, and finally a supervisor of production of airplane motor parts.

After the war, his voice restored, Hardt continued to study voice and appeared in starring roles in operettas and operas and as a symphony concert soloist. (His all-time favorite role: Danilo in Lehar’s The Merry Widow.)

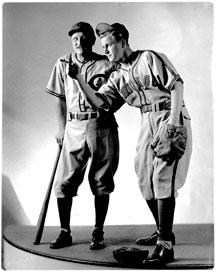

Chicago Tribune columnist Roy Topper wrote, “I have been taken to task by many readers for calling Robert Merrill the most handsome man in professional opera. They swarmed me with calls and letters advising me that one Herbert Hardt is so much better looking and many times more talented in the singing department!”

He won first prize in the Tribune’s vocal contest with a dramatic interpretation of Wagner’s “Valkyrie,” and offers began to roll in from the Chicago Lyric Opera, the St. Louis Muny Opera and even the New York Metropolitan Opera, but Hardt didn’t want to leave his family. He chose to return to the Old Heidelberg Inn, where he and his small orchestra packed the house for 13 years. That ended when an unscrupulous agent who wanted to replace Hardt with his client, planted a story in a Jewish newspaper in New York that Hardt had been a Nazi sympathizer. Most booking agents at that time were Jewish. Suddenly, no place in the country would hire Hardt.

“At first,” he says, “I felt angry, rejected and discriminated against, because I was completely innocent. I had heard Hitler’s speeches on the radio and couldn’t stomach what he was saying. But I came to realize that I couldn’t blame the Jews, who had suffered agony and humiliation. I decided that, as a German, perhaps this was something I just had to bear. I wasn’t disabled, and I could go on with my life.”

A friend joked that he knew of a great opportunity for Hardt – a ramshackle bar in Des Plaines. He and his wife transformed it into Herbi Hardt’s, a beautiful German-style restaurant that became so popular that the Saturday night special, a standing rib roast, was sold “by appointment only.”

Patrons from Texas, Ohio, New Jersey and all over Chicago followed him there. Hardt, Emily and their two children all worked in the business, which was tremendously successful. But Hardt, a devoted family man, was concerned that the booming business didn’t allow them much time together at home, so he sold the restaurant in 1961 and the family moved to Door County.

He and Emily bought her father’s property at the corner of Highway 42 and County A between Fish Creek and Ephraim, and for 12 years operated the motel that Alvin Ohman had built in 1951. It had been the first motel in the county – previous accommodations having been cottages and hotels – and the pool Hardt built behind it was also a Door County first, a fact that caused some other motel owners to cry unfair competition. The motel itself had instigated a petition drive – led by proprietors of other accommodations – who suggested that such establishments invariably became houses of ill repute.

Hardt and Emily also took over the 52 horses in the riding stable Ted operated across the street. In the early days, he’d led 20 of them across the highway and into Peninsula State Park every day for use by girls at Camp Meenahga. Eventually, he provided a shelter for the horses near the camp. The riding trails he laid out in 1929 are now the park’s cross-country ski trails. Hardt can tell many tales of the park’s early days, when the Kodankos and other families still had life tenancy there. He remembers that one of the Kodankos and a man named Casper Noah disappeared in the cedar swamp on County A, evidently swallowed by quicksand.

Hardt describes the Door County he first glimpsed in 1936 as pristine – little cottages, farms and orchards. He believes National Geographic’s 26-page story, “A Kingdom So Delicious,” published in March 1969, was the death knell of the old Door County. A big supporter of the campaign to build the Door Community Auditorium and chairman of the Fish Creek Civic Association for seven years, Hardt told that group that they’d be sorry someday if they didn’t raise the bridge and stop the influx of people.

Hardt sold the motel in 1973 and built a home at Hardt’s Acres across the road, where he still lives. Emily died in 1997. Hardt and his lady friend, Sarah Taylor, enjoy nature photography. He does most of his own home repairs and until two years ago, when he fractured a hip, rode his horse, Tina. (He still wears the western boots, shirts and big-buckled belt.) He speaks, reads and writes his native German fluently, and treasures his 1,500 recordings of classical music and his CDs, books and lectures on world religions. The phrase painted on the Baha’i’ meetinghouse next to his home reflects the core of his Baha’i’ faith: “The earth is but one country and mankind its citizens.”

At 98, Hardt’s goal is “to be the most informed person in the cemetery.” His chances are good!

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article said that the hotel Hardt ran in Ephraim was built by his father-in-law. That was incorrect. We regret the error.