Sen. Baldwin Discusses Opioid Crisis with Door County Officials

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

The opioid crisis that has ravaged rural communities across the country has yet to surface as a major problem in Door County, but the prospect of it becoming one weighs heavy on the minds of local leaders.

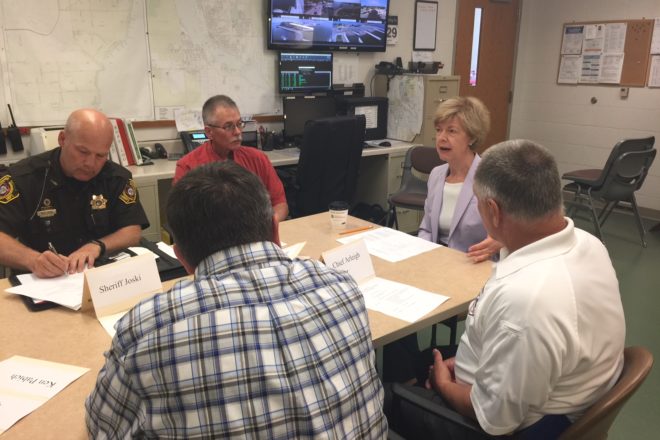

That was the message delivered to Sen. Tammy Baldwin at a roundtable discussion with local leaders May 29 in Sturgeon Bay.

“Tell me what you’re seeing on the ground and what you’re hearing about,” Baldwin asked the officials.

Baldwin specifically sought more information about price increases departments are facing for meloxin, also known as Narcan, an overdose reversal drug.

Chief Deputy Pat McCarty, Sturgeon Bay Police Chief Arleigh Porter, Door County Administrator Ken Pabich, Sturgeon Bay Mayor Thad Birmingham, Administrator Josh VanLieshout, Kewaunee County Sheriff Matt Joski, and Door County Human Services Director Joe Krebsbach spent an hour sharing their concerns in a meeting with the Senator at City Hall.

“The anxiety about it coming is large because the impact is so widespread if it gets here,” Krebsbach said.

Porter agreed.

“Probably the top three things that concern me are active shooter, heroin and fentanyl, and methamphetamine, in that order,” he said.

Krebsbach and Pabich emphasized that drug abuse has deep hidden costs that trickle down into a wide range of county services. When a parent becomes an addict, it doesn’t become simply a law enforcement or criminal justice issue. They need mental health services, treatment for addiction, and their children often end up in an already taxed foster care system. Krebsbach said the county is short on foster homes and had more placements than ever in 2017.

Though Door County fits the profile for heroin and opioid abuse in some ways with its high winter unemployment and high rates of suicide and mental health issues, it has unique advantages in staving off a crisis.

McCarty said the county’s isolated geography makes it difficult to get mass quantities of drugs in and out of the county, and a population heavy on retirees helps as well.

Still, he said there have been three overdose deaths in the county since 2015, and it doesn’t take a huge influx to cause major problems for the community and for budgets.

Krebsbach cited one patient, unrelated to drug abuse, that cost the county more than $200,000 last year, largely due to extended psychiatric treatment at a rate of $1,000 per day.

“We provide psychiatric services and in-patient care to lots of people,” he said. “We have 40 – 45 admissions every year. If they don’t have insurance, the county picks that tab up. Usually we’re under $400,000 a year. Last year was the worst in the 10 years since I’ve been director.”

Usually just a handful of cases take up half of his budget, Krebsbach said, and it’s not hard to imagine an influx of just a few opioid or heroin cases causing major budget problems for the county or city.

“If we come to a crisis, I really don’t know what our response would be,” VanLieshout said, pointing out that there’s little slack in local budgets, particularly since the levy cap was instituted.

“Right now we seem to be ahead of it a little bit,” Porter said, “but once you get behind, there’s no catching up.”

But staying ahead is difficult when budgets are already strapped. Officials agreed that prevention is their preferred approach, but it’s hard to prove the efficacy of prevention programs.

“I’m generally pleased that she’s showing interest in the issue,” Pabich said of Sen. Baldwin’s visit. “Each issue related is important – treatment and prevention are really important, but not as politically fancy. If you do prevention, how do you account for the cost-benefit?”

Krebsbach said that in the early part of his career much more emphasis was placed on prevention.

“We did more public education and community outreach,” he said. “Department staff was out in the community. Now, our therapists and workers are too busy with caseload to do prevention work. We’re providing services to people who already have problems, but not stopping people from developing the problem in the first place.”

Baldwin touted the Supporting and Improving Rural EMS Needs (SIREN) Act, led by Senators Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Pat Roberts (R-KS), which would reauthorize $20 million annually in competitive grant funding through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to support rural emergency medical services (EMS) agencies in training and recruiting staff, conducting courses to satisfy certification requirements and purchasing equipment – for everything from naloxone and first-aid kits, to power stretchers or new ambulances.

Baldwin said the act gives local agencies flexibility to use funds for what is needed there, rather than fit into a strict federal mandate that may not apply to local challenges.

“I see this as a bipartisan issue. It affects all of our states, and frankly, it affects everyone either directly or indirectly,” Baldwin said.

Before the meeting ended, Mayor Birmingham made a plea to Baldwin to return to the county to discuss mental health issues in Door County, specifically the lack of resources and funding available locally.