Steve Grutzmacher: Andrew Jackson and d’Artagnan

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

With the short turn around this week, I pulled a variety of pieces I write when I run across something that is interesting (at least to me). Neither of the following items ever developed into a column in and of themselves, but I still find them interesting and, hopefully, you will enjoy them, too.

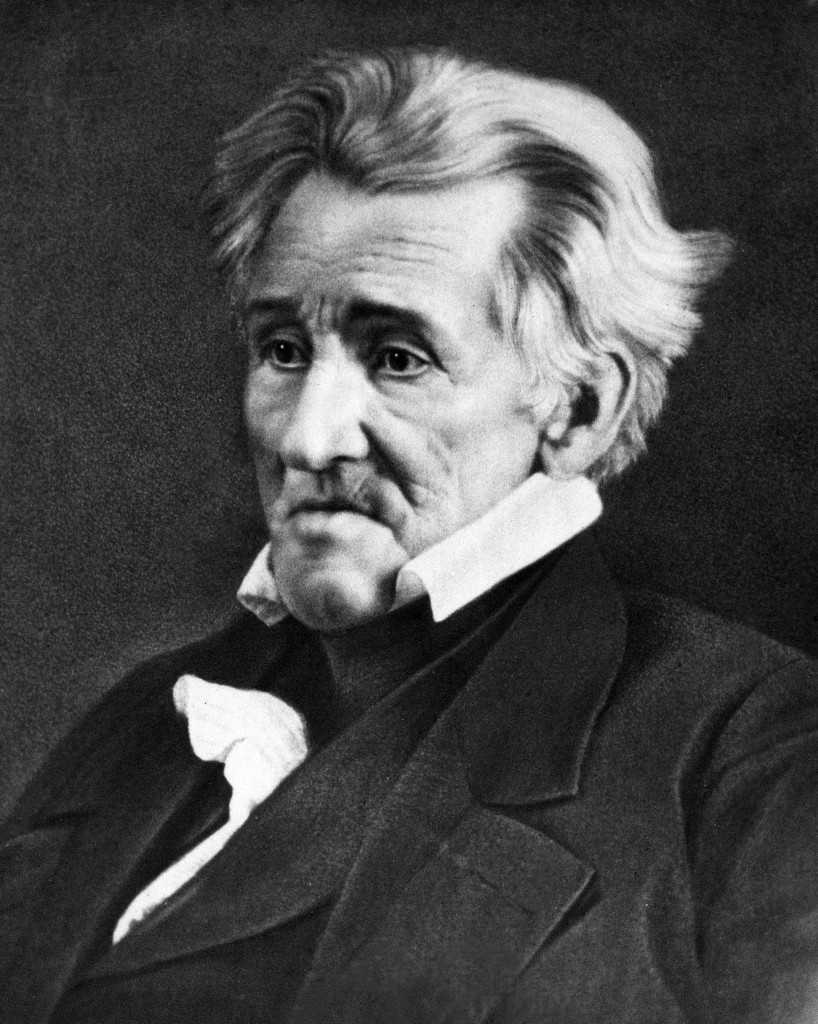

When Andrew Jackson was elected President he made it his personal mission to eradicate the federal debt. Remarkably, in 1834, Jackson succeeded and, on Jan. 1, 1835, the government actually posted a positive balance.

Jackson accomplished this feat, in part, through the elimination of the Second Bank of the United States. During his tenure he slowly funneled funds out of this bank and into selected state banks across the country. This had a result beyond bringing an end to the federal debt: it also greatly increased the amount of paper currency in circulation, which, in turn, resulted in spiraling inflation and rampant speculation. By 1836, the United States was experiencing its first great speculative bull market.

One of the chief areas of speculation was in land (Jackson, himself, became rich in land speculation prior to entering the political arena). At this time the government’s General Land Office handled the majority of land sales. In 1832 the General Land Office did $2.5 million dollars of business. By 1836, this figure had grown to $25 million and, during the early summer of this year, sales were totaling $5 million per month.

This, folks, is the origin of a phrase we all still know and, occasionally use: “doing a land office business.”

One of the misconceptions that I occasionally ran across during my years of selling books is that ardent readers of non-fiction often believe there is nothing to be learned from reading fiction. While there is certainly a large market for “recreational” or “escapist” fiction, there remains a vast array of fiction/literature available from which the reader can learn a great deal.

My case in point is one of my favorite authors: Arturo Pérez-Reverte. Other than when I was reading fantasy novels in my junior high and high school years, I can’t think of any other writer that I read more than two of their novels consecutively. In Pérez-Reverte’s case, I read three of his novels, one after the other.

Pérez-Reverte hooked me with his unique brand of mystery and suspense, rightly dubbed by reviewers as “intellectual thrillers.” After reading The Fencing Master and The Flanders Panel, I read The Club Dumas and the information which follows was discovered within the pages of this engaging novel (and subsequently verified in other sources).

Dumas, of course, is the famous French author of such notable novels as The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. These novels, like many of the novels of Charles Dickens over in England, were originally published as serials, appearing in monthly installments in popular periodicals. This much was common knowledge, at least to me, but from this point Pérez-Reverte provided some enlightening further background.

The Three Musketeers was published in installments in La Siecle between March and July of 1844. Dumas regularly used collaborators or ghostwriters, and he received help on Musketeers from Auguste Maquet, who also helped with the sequel, Twenty Years After, and on The Vicomte de Bragelonne (which completed the Musketeers series). Maquet also worked with Dumas on The Count of Monte Cristo.

The character of d’Artagnan was based on Charles de Batz-Castelmore, Comte d’Artagnan, who was born in 1615 and was an actual musketeer. He was killed during the siege of Maastricht when he was on the verge of being awarded the marshal’s staff, like Dumas’ character.

Athos was based on Armand de Sillegue, Lord of Athos. Aramis was really Henri d’Aramitz; and Porthos was actually Isaac de Portau. Of this assortment of historical people, only d’Aramitz and de Portau actually knew one another, since both were musketeers in the mid-1640s.

And finally, there really was a Milady (Anne de Breuil) and she wasn’t the Duchess de Winter. Her name was the Countess of Carlisle and she actually was a spy for Cardinal Richelieu who really stole two diamond tags from the real Duke of Buckingham.

While I acknowledge this may be “useless information” to many of you, I think it makes a strong case that you can, indeed, learn a great deal from reading fiction.