Sustainability 2019: The Housing Issue

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

From age 19 to 31, I was a year-round resident of northern Door County. I lived in 13 homes and apartments in seven municipalities from Egg Harbor to Liberty Grove. Some I owned; some I rented; in all of them I had roommates. I worked full time that entire time, and more than 60 hours per week for most of it.

Two of those apartments were part of properties that accompanied the restaurant I owned, and just four of them were found through a listing. The rest came through a friend giving up a room, from a family member catching an inside tip or by stumbling into the right conversation at a bar or coffee shop (and my editors thought I was just wasting time on those stools!). The best of those homes came by pestering the owner of a vacation rental into leasing to me in the days before Airbnb made it easy to rent your home to vacationers.

Three times I had to move because a home was going on the market. Two other apartments were summer rentals only. Two were taken to the vacation-rental market. Other times I moved when time was up on a room or a slightly better dump became available.

My story is not atypical. A simple glance at real estate listings tells us that home prices are out of reach for the average Door County worker, but for hundreds – if not thousands – of fully employed residents of Door County, an affordable rental unit is even more difficult to find.

The housing study released by the Door County Economic Development Corporation in February made this clearer than ever. It was ridiculed by many as pointing out the obvious.

“We didn’t need an expensive study to tell us this,” was a common refrain on Facebook. That’s true, but a review of the study shows that it does more than just tell us what we already knew.

Where the study breaks new ground is in quantifying the amount of housing needed and where. In sum, it showed a current gap of 470 workforce rental apartments, with 140 needed in northern Door County and 330 in the Sturgeon Bay area. The potential occupants of these apartments are identified as people who want to live here but can’t find housing. It also anticipates an additional 110 will be needed by 2023.

In northern Door County, these are potential tourism-industry workers, tradespeople, even newspaper reporters. In the city, it’s all of those plus the hundreds of workers manufacturers say they need to keep up with demand. Throughout the county, there is a growing senior population struggling to find apartments as well.

Municipal officials say the study is already helping to draw interest from builders.

“It’s a useful tool,” said Egg Harbor Village Administrator Ryan Heise. “For example, I introduced myself to a builder in Neenah and sent them the housing study. That quantifies our needs. That conversation becomes a lot more serious a lot faster with that information at hand.”

The study also looks at the incomes of those people looking for housing. The Village of Sister Bay and the City of Sturgeon Bay have led the way in developing more housing units. Sister Bay’s push began a decade ago, at the bottom of the recession, when builders such as Keith Garot were enticed by projects that would keep cash flow coming in, even if profit margins were smaller. Garot built dozens of townhomes that sold for $89,900 to $140,000 – a price point impossible to come by at that time.

But years later, only 27 of his original 75 townhomes are owned by people with Door County addresses. It is one of the biggest fears of communities when they approve affordable projects: the units simply become vacation rentals or second homes. But still, that’s 27 residents who likely wouldn’t otherwise own a home. It was a start.

In Sturgeon Bay, roughly 150 rental apartments have come on the market in recent years or will come on the market soon. Sister Bay has 84 in the works. Both communities tout these as “workforce housing,” and they undoubtedly are filling a needed niche in the market. But if you define “workforce” using the median income of a Door County worker, these apartments aren’t even scratching the surface of addressing the affordable-housing shortage.

Nearly all of these apartments rent for more than $810 per month, and many for more than $1,000 per month. At the February Housing Summit where the housing study was announced, Chris Loose of Lakeshore CAP put this in perspective.

Using the benchmark of 28 percent of income going toward housing costs, a household making the median household income of about $54,000. With no debt or child-care payments, this household can afford a $1,275 monthly housing payment. But who is this mythical worker with no debt?

“Add in $250 in student loans and $300 for a car payment, and you very quickly can afford much less,” Loose said. A modest medical condition, high health-insurance costs, or a child-care payment make the situation even worse. These people, realistically, should not even enter into the thought of buying a home yet.”

If the recession of 2008 taught us anything, it’s that we shouldn’t push home ownership for all as the key to economic prosperity. But what if people can’t even afford to rent? In Door County, that’s increasingly the case. Remember all those apartments Sister Bay and Sturgeon Bay are touting? Well, as Loose puts it, not a single one of them would qualify as affordable for a person making the median household income in Door County if they have even a modest car payment, student-loan payment or credit card debt.

The Forgotten Factor in the Seasonal Housing Gap

488.

That number hasn’t been mentioned in any of the housing discussions I’ve been a part of in the last decade and a half, but it plays a major role in why we’re so desperate to find housing for seasonal workers.

That’s the number of fewer students in Door County’s four mainland high schools today compared to 20 years ago. That represents 488 potential workers. (When I graduated from Gibraltar High School in 1997, I knew very few contemporaries who didn’t work 40-plus hours per week by their freshman year of high school.) Add in the fact that many of them would likely return to the county to work as 19- and 20-year-olds, and we’ve lost six years’ worth of workers.

What was one of the best things about all of those workers, besides the fact that they were available on fall weekends? They all had housing.

Now the county’s businesses have to replace those lost workers with employees imported from outside the county and outside the country, few of whom have a connection to a local resident and all of whom need a bed.

Builders Cite Hurdles to Affordability

For builders, the path to affordability is a math problem. Land prices, sewer and well costs, minimum lot sizes and density limits all drive up costs. Add the spate of natural disasters, tariffs on imported lumber and steel, and a tight labor market, and you have construction costs that are up 30 percent by some estimates.

“There’s just no way you can build the stuff any cheaper with the cost of material and labor and land prices,” said Tim Halbrook, who has built nearly 90 apartments in Sister Bay in recent years. “And a lot of these properties have to be rezoned, so then you have a bunch of neighbors opposing it.”

Not only is there little housing below $180,000, but much of what exists in the $180,000 to $350,000 range is dated and comes with a ticket for a new roof, heating and cooling system, or other high-cost repairs and upgrades. (I saw this up close when I looked at 31 houses in this range when my wife and I decided to move home in 2017.)

“In Green Bay, where I’m from, there are used houses a young couple can buy for $150,000,” Halbrook said. “There are no houses up here you can buy for $150,000. That same house up here might be $250,000, and it needs a ton of work. They’re overpriced, and people have done nothing to them.”

Minimum lot sizes add to the cost to build in rural areas, and minimum home sizes make it hard to get tiny homes or tiny-home complexes off the ground.

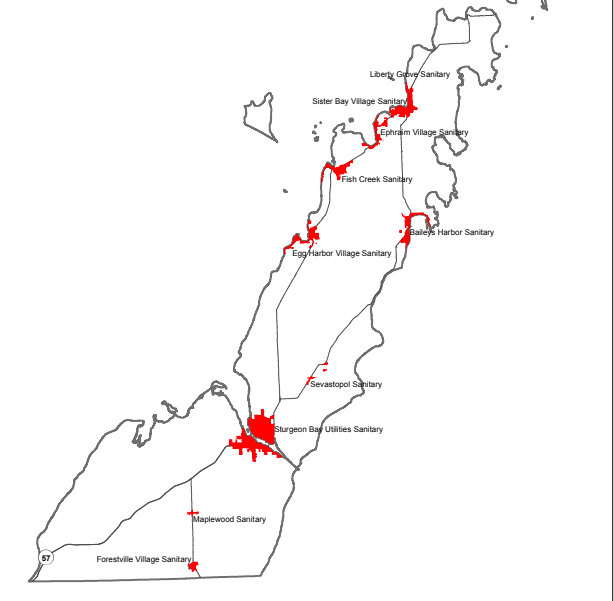

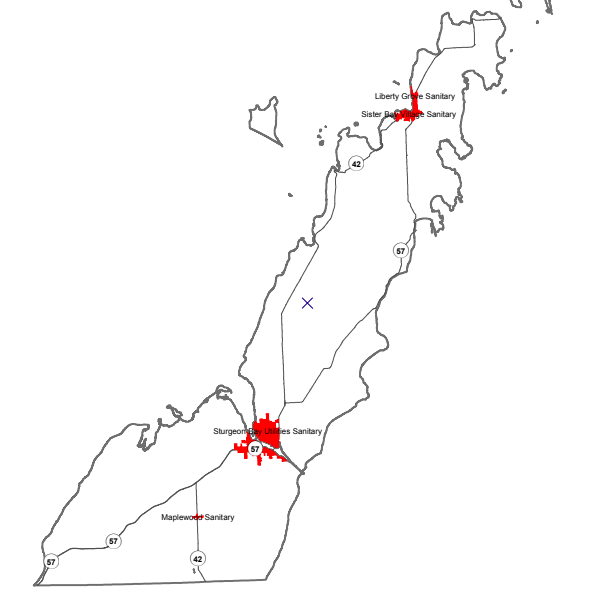

Public sewer and water infrastructure makes it much easier to build more affordable homes, but only Sister Bay and Sturgeon Bay have both, and a few other communities have just one of the two. A look at the accompanying maps shows just how little of the county’s land is covered by public water and/or sewer. A well and septic system can add $15,000 to $25,000 to the cost to build a new home.

If communities allow for greater density and smaller lot sizes, shared wells and septics can bring costs down, but then you have to find a builder who wants to take on that project instead of a higher-profit, $400,000 home.

Hope for Action

Despite the laundry list of roadblocks standing between home-seekers and affordability, there are signs that the county may finally be at a tipping point that spurs dramatic action. The housing study is opening the eyes of municipal leaders at a time when many of them are feeling the pinch in their own businesses or families.

The Town of Liberty Grove, Village of Egg Harbor and Town of Gibraltar have all indicated a willingness to make land available for affordable homes or apartments. The Door County Economic Development Corporation has made housing a priority, as has the Interfaith Poverty Coalition.

In the pages that follow, we’ve gathered voices from all corners of the housing struggle. You’ll find the stories of retirees seeking apartments, mothers desperate for a good home for their family, and business owners finding solutions for their workers.

You’ll find ideas that are practical and some that are seemingly far-fetched, but they’re all taken from the conversations we’re hearing in boardrooms and coffee shops. Could shipping containers play a role in closing the seasonal housing gap? How about tiny homes and campgrounds?

On the home-ownership front, Mariah Goode explains the possibilities of a housing trust to create affordable home stock in perpetuity, and Virge Temme discusses the many factors outside the home structure that influence affordability. And Jim Lundstrom looks at a development felled by a common housing nemesis: Nimbyism.

Jackson Parr examines how zoning changes have opened windows to more development options and changes that could take them even further. He also explores how the growth of vacation rental sites such as VRBO and Airbnb are affecting home and rental markets.

There are many more issues to dig into, and we’ll get to them in time. But with this year’s Sustainability Issue, we hope to simply throw a lot of ideas at the wall to start or further conversations.

Thirteen years ago, Dave Eliot and I cooked up the idea of the Sustainability Issue based on the idea of sustainable development. We wanted to pause once a year to take a look at how Door County could evolve without costing ourselves the things we value so much here. At the time, our minds were on the environment, but now it’s on something else we value: our people.

If our leaders, business owners and residents fail to address our myriad housing issues in a meaningful way, our economy won’t be able to support itself. There will be no cooks to work the line, no plumbers to stop the leak, no nurses to care for our elderly, no young families filling the halls of our schools – and eventually, a community that no longer reminds us of the place we fell in love with in the first place.

In short, the Door County we know becomes unsustainable.